Alex-Haifa-Alex-Kalymnos

Alex-Haifa-Alex-Kalymnos

Theirs not to reason why.

Theirs but to do and die.

(from The Charge of the Light Brigade)

Within two hours upon our return to Alexandria from Taranto, Italy, on October 12, 1943, we were ordered to sail to Haifa to have the (engine) boilers cleaned—nothing unusual about it.

We arrived in Haifa in the early morning hours of October 13, and without delay, the maintenance service crews went to work.

We stayed there for five days busying ourselves with the usual port duties and ship maintenance chores. The second-day Toumbas called an officers' meeting. We had a feeling that something big was in the air. Toumbas didn't mince any words. He told us right at the beginning that we would be participating in the Dodecanese Campaign!

He went on detailing the Allied strategy that was fraught with danger. And although he was hoping for the best he admonished us to prepare for the worst. He asked all present to re-evaluate the needs for their respective areas of operation and get enough supplies necessary to keep the ship afloat, in the worst case scenario. In hindsight, by not sugarcoating the danger, Toumbas somehow prepared us psychologically for what was to come!

Sacks of cement, extra tools, wood beams, and other emergency items were loaded. We were ready to sail. We left Haifa just after midnight of October 19, 1943, and arrived in Alexandria in the late afternoon. For the next two days, we participated in various anti-aircraft firing exercises with a couple of other ships, and we were looking forward to some R&R. But that was not meant to be.

Late in the evening of October 20, came the order for deployment to the Dodecanese Islands. Sudden ship departures were nothing unusual. Actually, there was a rather "primitive" system in place whereby ship-messengers would go around movie theaters, coffee houses, brothels, hotel lobbies and other places where officers and crews were usually frequenting, while on shore leave, to alert them. Oftentimes, movie theaters would interrupt a movie to announce "officers and crews of xyz-ship report to your ship, immediately!"

As a matter of fact, our departure was so sudden that some men who could not be located were left behind, like Ensign Saliaris. I would have been one of them too, if it were not for Androulakis who knew that I was visiting with the Argyris family—he came and got me.

Theirs but to do and die.

(from The Charge of the Light Brigade)

Within two hours upon our return to Alexandria from Taranto, Italy, on October 12, 1943, we were ordered to sail to Haifa to have the (engine) boilers cleaned—nothing unusual about it.

We arrived in Haifa in the early morning hours of October 13, and without delay, the maintenance service crews went to work.

We stayed there for five days busying ourselves with the usual port duties and ship maintenance chores. The second-day Toumbas called an officers' meeting. We had a feeling that something big was in the air. Toumbas didn't mince any words. He told us right at the beginning that we would be participating in the Dodecanese Campaign!

He went on detailing the Allied strategy that was fraught with danger. And although he was hoping for the best he admonished us to prepare for the worst. He asked all present to re-evaluate the needs for their respective areas of operation and get enough supplies necessary to keep the ship afloat, in the worst case scenario. In hindsight, by not sugarcoating the danger, Toumbas somehow prepared us psychologically for what was to come!

Sacks of cement, extra tools, wood beams, and other emergency items were loaded. We were ready to sail. We left Haifa just after midnight of October 19, 1943, and arrived in Alexandria in the late afternoon. For the next two days, we participated in various anti-aircraft firing exercises with a couple of other ships, and we were looking forward to some R&R. But that was not meant to be.

Late in the evening of October 20, came the order for deployment to the Dodecanese Islands. Sudden ship departures were nothing unusual. Actually, there was a rather "primitive" system in place whereby ship-messengers would go around movie theaters, coffee houses, brothels, hotel lobbies and other places where officers and crews were usually frequenting, while on shore leave, to alert them. Oftentimes, movie theaters would interrupt a movie to announce "officers and crews of xyz-ship report to your ship, immediately!"

As a matter of fact, our departure was so sudden that some men who could not be located were left behind, like Ensign Saliaris. I would have been one of them too, if it were not for Androulakis who knew that I was visiting with the Argyris family—he came and got me.

lick here to edit.

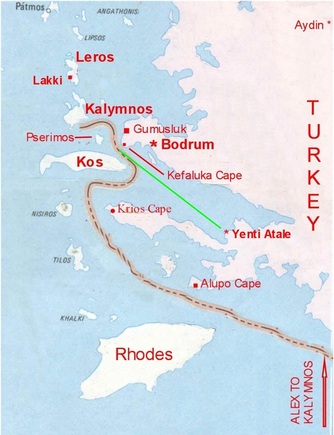

Route to Kalymnos

On October 21, 1943, at 3:00 a.m. Adrias sailed for the Dodecanese with three other destroyers, Jervis, Pathfinder, and Hurworth. The first two were Fleet Destroyers whereas Hurworth and Adrias were Escort Destroyers. All four ships were loaded with stores and ammunition for the British garrisons in Leros.[1]

I do not know if the day of departure was a coincidence or part of the plan. October 21, is a very significant date in the British Naval history. It’s the anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 when Admiral Lord Nelson delivered a crushing defeat on the Franco-Spanish armada.

Our mission was to decoy the Germans away from Leros. The overall plan was for two of the ships to enter the port of Lakki, in Leros, to unload while the other two would engage in diversionary activities in Kalymnos to distract the Germans' attention from Leros. And the following night the roles would be reversed.

Hurworth and Adrias were assigned to do the diversionary activities the first night. Commander Royston Hollis Wright [2] was the skipper of the Hurworth and the flotilla commander—known to all as "Captain D22," or simply "Captain D," short for 22nd Destroyer Flotilla Leader.

On the way up, we were moving fast not to miss our rendezvous with the light cruiser Aurora and our destroyer Miaoulis. These two ships were supposed to provide us with air protection during the day in case we were attacked by German planes from nearby Rhodes. We met with them around 12 noon and the order to assume battle stations came down. Around 7:00 p.m. our escorts Aurora and Miaoulis, detached and we proceeded independently. About an hour later we left behind our two partners Jervis and Pathfinder. Meanwhile, the two of us, Hurworth and Adrias, continued at a faster clip toward Kalymnos to begin our diversionary activities. According to Allied Intelligence, we were supposed to find several merchant ships at the coves of Vathi and Akti that we were supposed to sink.

We sailed close to the Turkish coastline all the way up to cape Alupo, across from Rhodes. We passed Simi from the left and rounded Cape Krios in the Datca peninsula. We continued north and at the level of Bodrum, we turned left hugging the Turkish coast up to cape Kefaluka where we entered the strait of Kos—an extremely narrow passage within range of the coastal artillery from the German-occupied Kos.

Around 1:30 a.m. we were at our destination, cruising outside Bathi, Kalymnos. My turret was ready to commence firing the instant Lt. Sotiriou, the Artillery Officer, gave the order. It was pitch dark. All eyes in the turret were piercing the darkness looking for enemy ships. But none was to be found! We sailed a bit south to another cove, Akti, but nothing was there either. We slowed down coming closer to the shore, looking inside smaller coves in case there were ships hiding. But not such luck! Finally, we boldly turned on our searchlights hoping to attract the Germans' attention. Meanwhile, the fleet destroyers that were much faster passed us going at full speed to get to Leros to unload men and supplies and get out before being detected by the Germans. For two hours we (Hurworth and Adrias) were cruising parallel to the coastline with searchlights blazing; searching for targets and making as much "noise" as we could. We were all very disappointed!

I do not know if the day of departure was a coincidence or part of the plan. October 21, is a very significant date in the British Naval history. It’s the anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 when Admiral Lord Nelson delivered a crushing defeat on the Franco-Spanish armada.

Our mission was to decoy the Germans away from Leros. The overall plan was for two of the ships to enter the port of Lakki, in Leros, to unload while the other two would engage in diversionary activities in Kalymnos to distract the Germans' attention from Leros. And the following night the roles would be reversed.

Hurworth and Adrias were assigned to do the diversionary activities the first night. Commander Royston Hollis Wright [2] was the skipper of the Hurworth and the flotilla commander—known to all as "Captain D22," or simply "Captain D," short for 22nd Destroyer Flotilla Leader.

On the way up, we were moving fast not to miss our rendezvous with the light cruiser Aurora and our destroyer Miaoulis. These two ships were supposed to provide us with air protection during the day in case we were attacked by German planes from nearby Rhodes. We met with them around 12 noon and the order to assume battle stations came down. Around 7:00 p.m. our escorts Aurora and Miaoulis, detached and we proceeded independently. About an hour later we left behind our two partners Jervis and Pathfinder. Meanwhile, the two of us, Hurworth and Adrias, continued at a faster clip toward Kalymnos to begin our diversionary activities. According to Allied Intelligence, we were supposed to find several merchant ships at the coves of Vathi and Akti that we were supposed to sink.

We sailed close to the Turkish coastline all the way up to cape Alupo, across from Rhodes. We passed Simi from the left and rounded Cape Krios in the Datca peninsula. We continued north and at the level of Bodrum, we turned left hugging the Turkish coast up to cape Kefaluka where we entered the strait of Kos—an extremely narrow passage within range of the coastal artillery from the German-occupied Kos.

Around 1:30 a.m. we were at our destination, cruising outside Bathi, Kalymnos. My turret was ready to commence firing the instant Lt. Sotiriou, the Artillery Officer, gave the order. It was pitch dark. All eyes in the turret were piercing the darkness looking for enemy ships. But none was to be found! We sailed a bit south to another cove, Akti, but nothing was there either. We slowed down coming closer to the shore, looking inside smaller coves in case there were ships hiding. But not such luck! Finally, we boldly turned on our searchlights hoping to attract the Germans' attention. Meanwhile, the fleet destroyers that were much faster passed us going at full speed to get to Leros to unload men and supplies and get out before being detected by the Germans. For two hours we (Hurworth and Adrias) were cruising parallel to the coastline with searchlights blazing; searching for targets and making as much "noise" as we could. We were all very disappointed!

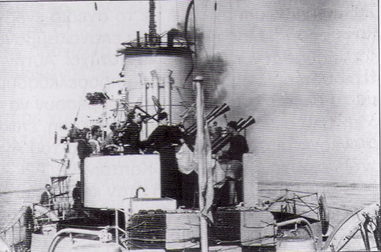

Adrias POM-POM in action

Adrias POM-POM in action

Around 3:00 a.m. "Captain D" gave the order to return to our rendezvous position, in neutral Turkish waters, assuming that Jervis and Pathfinder had succeeded in delivering their loads.

Suddenly we see lights from the direction of Kos. Sure enough, within minutes we were attacked by Stukas, while other planes were dropping an inordinate number of flares that turned the darkness of the night into daylight. The illumination was so strong that we could see our shadows.

Both ships sped up and commenced zigzagging. Hurworth was attacked first. We saw it disappear behind huge columns of water raised by the bombs. But as the columns of water subsided we saw her riding the waves intact. Apparently, the bombs had missed her. But then the furry of the Stukas turned on us. This was the most intense and longer lasting air attack Adrias ever endured.

While dive-bombers were attacking us, other planes were constantly dropping flares. So brilliant was the coruscation that the entire area was illuminated as if it were the middle of the day. And if that was not enough of a problem, the radar on both ships was unable of detecting incoming aircraft due to interference caused by the jagged silhouettes of the mountain peaks on the surrounding islands. Thus intensifying our sense of being surrounded by danger, enemies, and hidden perils. So, to avoid making it easier for the Germans to see us we did not fire back.

All men on Adrias were veteran fighters, tough and with nerves of steel. We all understood our lives were hanging in the balance of a great number of factors, the most important of them being our skipper's “ear.” The reason being that in the darkness of the night, and without radar, commander Toumbas had to "guess" from that screeching/whistling sound of the diving [3] Stukas when to order the helmsman to turn the wheel to dodge the bombs.

Consequently, absolute silence reigned on the ship, not even a whisper or a sigh could be heard. And, although it was a matter of seconds between attacks, no bomb hit Adrias. A testament to luck and to Toumbas' masterful seamanship!

Zigzagging and the sudden turns at high speed, oftentimes, made the ship list more than 20 degrees. But all men stood at their stations, holding to stanchions lest be washed overboard, waiting for whatever could happen next. Meanwhile, the bombs falling around us raised enormous columns of water drenching everyone and creating massive waves smashing onto the sides of the ship accentuating Adrias' pitching and rolling and causing the deck edge occasionally to be underwater. Several times I thought that we were sinking. Nevertheless, morale seemed higher than should have been possible under the circumstances.

At some point during the battle, Hurworth had the bright idea of throwing in the water a smoke float. That did the trick! The Stukas' fury was diverted to the float. That gave us the opportunity to pull out in a hurry and disappear into the darkness of the night steaming at flank speed toward our rendezvous point in the neutral waters of Turkey. But as we were rounding cape Kefaluka, a bit too close to shore, we received small gunfire from the Turkish shore garrisons, luckily there were no casualties. So we continued toward our rendezvous minding our business, without engaging the Turks.

Suddenly we see lights from the direction of Kos. Sure enough, within minutes we were attacked by Stukas, while other planes were dropping an inordinate number of flares that turned the darkness of the night into daylight. The illumination was so strong that we could see our shadows.

Both ships sped up and commenced zigzagging. Hurworth was attacked first. We saw it disappear behind huge columns of water raised by the bombs. But as the columns of water subsided we saw her riding the waves intact. Apparently, the bombs had missed her. But then the furry of the Stukas turned on us. This was the most intense and longer lasting air attack Adrias ever endured.

While dive-bombers were attacking us, other planes were constantly dropping flares. So brilliant was the coruscation that the entire area was illuminated as if it were the middle of the day. And if that was not enough of a problem, the radar on both ships was unable of detecting incoming aircraft due to interference caused by the jagged silhouettes of the mountain peaks on the surrounding islands. Thus intensifying our sense of being surrounded by danger, enemies, and hidden perils. So, to avoid making it easier for the Germans to see us we did not fire back.

All men on Adrias were veteran fighters, tough and with nerves of steel. We all understood our lives were hanging in the balance of a great number of factors, the most important of them being our skipper's “ear.” The reason being that in the darkness of the night, and without radar, commander Toumbas had to "guess" from that screeching/whistling sound of the diving [3] Stukas when to order the helmsman to turn the wheel to dodge the bombs.

Consequently, absolute silence reigned on the ship, not even a whisper or a sigh could be heard. And, although it was a matter of seconds between attacks, no bomb hit Adrias. A testament to luck and to Toumbas' masterful seamanship!

Zigzagging and the sudden turns at high speed, oftentimes, made the ship list more than 20 degrees. But all men stood at their stations, holding to stanchions lest be washed overboard, waiting for whatever could happen next. Meanwhile, the bombs falling around us raised enormous columns of water drenching everyone and creating massive waves smashing onto the sides of the ship accentuating Adrias' pitching and rolling and causing the deck edge occasionally to be underwater. Several times I thought that we were sinking. Nevertheless, morale seemed higher than should have been possible under the circumstances.

At some point during the battle, Hurworth had the bright idea of throwing in the water a smoke float. That did the trick! The Stukas' fury was diverted to the float. That gave us the opportunity to pull out in a hurry and disappear into the darkness of the night steaming at flank speed toward our rendezvous point in the neutral waters of Turkey. But as we were rounding cape Kefaluka, a bit too close to shore, we received small gunfire from the Turkish shore garrisons, luckily there were no casualties. So we continued toward our rendezvous minding our business, without engaging the Turks.

Christos on Adrias

Christos on Adrias

Around 7:00 a.m. all four ships dropped anchor in the Turkish cove of Yenti Atala. We spent most of the day relaxing—a euphemism, perhaps—and repairing the damages caused by last night's bombs and bullets without being bothered by either the Germans or the Turks.

Despite all, we had endured last night, bombs, hunger, cold, and lack of sleep we were confident of our ability to prevail over the enemy. So we eagerly waited for the afternoon officers' meeting Toumbas has called to inform us about the plans for the night's operations.

"Gentlemen," Toumbas said after a long silence, "I would like to informed you about tonight's operations, and yes" —he looked directly at us—"we would have to repeat last night diversionary operations." Some inquisitive and rather disappointing glances went around the room which Toumbas ignored. He continued, "Jervis and Pathfinder were unsuccessful delivering the supplies to Leros." He glanced at the map on the wall and touched his fingers to the island labeled KALYMNOS. "When we reach Kalymnos we should make 'lots' of noise." He looked from face to face and as he had hoped, that dispersed some of the tension. Everyone was calm, no questions were asked. So he continued, "we got to divert their [Germans] attention to us so Jarvis and the Pathfinder can deliver their loads without being bothered by German planes."

Then he pulled from his pocket a piece of paper, and read Captain D's Laconic order: "Same drill as last night." And with a "Thank you all and Godspeed," Toumbas adjourned the meeting and issued the order: "prepare for departure."

The briefing was informative, decisive, and clearly understood. There was no need for questions and none was asked. There was a determination on everyone's face to do their best even if that meant losing our lives. As usual, Toumbas did not try to hide or minimize the danger we were facing. Nevertheless, his willingness to take greater risks to make sure that ADRIAS played her part toward the success of the mission set the adrenaline flowing in all of us! Later on, the scuttlebutt had it that Toumbas' response to Captain D's order to "make noise " was: "We Greeks are used to making a lot of noise !"

As my friend K. Themelis and I were making our way out of the Officers' Lounge to get to our respective stations, I noticed a strange but serious smile on his face. Perhaps he saw the same in mine. We wished each other "good luck" and parted our ways, he for the fore turret and I for the aft.

During the preparation of my turret, I came across my old Cretan friend, Androulakis. He was plugging the bullet holes on a lifeboat from last night's strafing by the Turks. He had learned carpentry from his father and he was the "de facto" ship's carpenter. We started chitchatting and inevitably the conversation came to what was in store for us later on in the evening. Mind you, Androulakis was a brave young man and he had proven it many times, so I was surprised when he told me "once this war is over, I don't want to work on or have anything to do with ships."

I did not think much of it and after wishing "good luck " to each other I left to inspect my turret's readiness. And when all was in order I reported to the executive officer: "Aft Turret ready for departure, sir."

And at nightfall, under cover of darkness, ADRIAS sailed for her rendezvous with history.

________________________________________________

[1] After the Italian surrender The Allies had captured several Dodecanese islands in the early part of 1943.

But lost Kos and other islands to the Germans by October 1943. After that reversal of fortunes, The Allies

focused on supply missions to the threatened islands of Leros and Samos.

[2] Later Admiral Sir Royston Hollis Wright, GBE, KCB, CB, DSC and Bar, and Second Sea Lord.

[3] The plane was equipped with sirens that made a sort of a screeching/whistling sound as the Stuka dove for psychological effect.