Christos, Cadet

Christos, Cadet

"Tell me, O muse, of those ingenious heroes

who traveled far and wide after they escaped from

the German occupied city of Athens."

(paraphrasing Homer)

Our long road to Alexandria, Egypt, began when the Academy-encouraged oblivion to Greece's ongoing war with Italy was suddenly interrupted by a huge explosion in the early morning hours of April 7, 1941. The shock wave blew-in the window casings of our sleeping quarters. It was a miracle that there were no casualties.

We jumped out of our bunks and ran downstairs to the main mess hall, wearing only our skivvies. With the collapse of the Greco-Yugoslav front the day before, the Germans had begun a massive bombing raid on the port of Piraeus. A bomb hit the British ammunition ship Clan Fraser with devastating results for the harbor and its surrounding area. The explosion, besides the casualties, made hundreds of people homeless and resulted in the abandonment of certain sections of the town until a few years after the end of the war.

Under these circumstances, and with the Germans advancing toward Athens, the Academy closed its doors that morning issuing an indefinite leave of absence to all cadets.

who traveled far and wide after they escaped from

the German occupied city of Athens."

(paraphrasing Homer)

Our long road to Alexandria, Egypt, began when the Academy-encouraged oblivion to Greece's ongoing war with Italy was suddenly interrupted by a huge explosion in the early morning hours of April 7, 1941. The shock wave blew-in the window casings of our sleeping quarters. It was a miracle that there were no casualties.

We jumped out of our bunks and ran downstairs to the main mess hall, wearing only our skivvies. With the collapse of the Greco-Yugoslav front the day before, the Germans had begun a massive bombing raid on the port of Piraeus. A bomb hit the British ammunition ship Clan Fraser with devastating results for the harbor and its surrounding area. The explosion, besides the casualties, made hundreds of people homeless and resulted in the abandonment of certain sections of the town until a few years after the end of the war.

Under these circumstances, and with the Germans advancing toward Athens, the Academy closed its doors that morning issuing an indefinite leave of absence to all cadets.

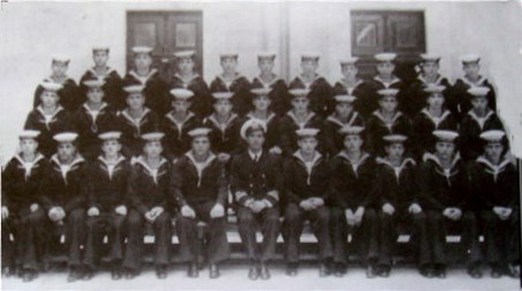

Cadet Class of 1939,

Christoe, 6th, 2nd row, L-R

Cadet Class of 1939,

Christoe, 6th, 2nd row, L-R

While my fellow cadets and I were milling about Athens, we learned that the first- and second-year Army cadets were escaping to Crete where the Army and the Navy had retreated to avoid capture by the Germans. So, we, Naval Cadets, started making plans for going to Crete. After a number of meetings that went nowhere, the group dwindled down to three: My two classmates, Constantinos "Costas" Notaras, Pericles Soutsos, and me.

Costas' and my parents gave us their blessings but Pericles' father had reservations. He tried to convince us to abandon our plans as being premature and too risky. Perikles and I were good friends and his parents were fond of me. They had a beautiful home with a garden in the suburbs of Athens where I had stayed many times as their guest. Unfortunately, though, I had to lie to his father the morning of our departure fearing that he may prevent Pericles from joining us. Sadly, and considering what happened later[1], I never saw him again to apologize for lying to him.

Costas' and my parents gave us their blessings but Pericles' father had reservations. He tried to convince us to abandon our plans as being premature and too risky. Perikles and I were good friends and his parents were fond of me. They had a beautiful home with a garden in the suburbs of Athens where I had stayed many times as their guest. Unfortunately, though, I had to lie to his father the morning of our departure fearing that he may prevent Pericles from joining us. Sadly, and considering what happened later[1], I never saw him again to apologize for lying to him.

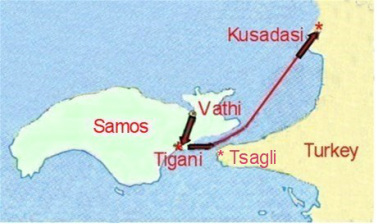

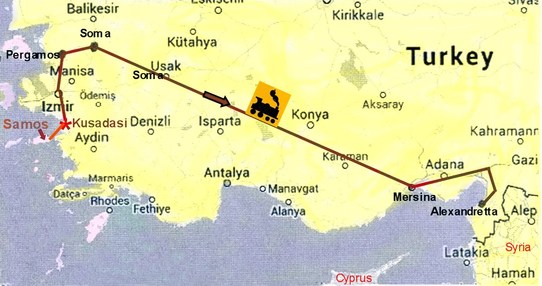

The long road to Alexandria (Athens-Alexandria)

The long road to Alexandria (Athens-Alexandria)

In the morning of April 23, 1941, St. George's feast day, the three of us and my sixteen-year-old brother, Mimis, began a perilous journey that would eventually keep us away from home for the next four years.

Our initial plan was to go to Crete through the Peloponnese. But we had no means of transportation. Moreover, the Kakia Skala was bombed and the Corinth Canal (Isthmus) was occupied by a German Air Force detachment.

During the Second World War the Corinth Canal (the Isthmus) had become very important to both the Germans and the Allies, but for different reasons. The Allies planned and executed numerous operations to put it out of commission; to prevent oil from the Black Sea reaching Italy, to delay the invasion of Crete, and to sever the vital German supply lines to Rommel's Army in North Africa, and prevent the cut off of the ANZAC retreat.

So we took a taxi to the port of Lavrion where the Harbor Master was a certain P. Tsakiris whom the three of us knew from our Academy's last training trip aboard the Academy's ship. Additionally, Pericles' family had a summer house and a small boat there. Upon arrival, we informed Tsakiris of our plans to take the boat to Crete. While preparing the boat, Tsakiris visited us. He took a look at the boat and with a sense of bewilderment, said: “Where are you going with this karidotsouflo[2]?” And then, casting another pitiful glance at our tiny boat, he said: “There is a boat at Thorikon, a short distance north from here, she is going to Crete and needs a crew.”

Our initial plan was to go to Crete through the Peloponnese. But we had no means of transportation. Moreover, the Kakia Skala was bombed and the Corinth Canal (Isthmus) was occupied by a German Air Force detachment.

During the Second World War the Corinth Canal (the Isthmus) had become very important to both the Germans and the Allies, but for different reasons. The Allies planned and executed numerous operations to put it out of commission; to prevent oil from the Black Sea reaching Italy, to delay the invasion of Crete, and to sever the vital German supply lines to Rommel's Army in North Africa, and prevent the cut off of the ANZAC retreat.

So we took a taxi to the port of Lavrion where the Harbor Master was a certain P. Tsakiris whom the three of us knew from our Academy's last training trip aboard the Academy's ship. Additionally, Pericles' family had a summer house and a small boat there. Upon arrival, we informed Tsakiris of our plans to take the boat to Crete. While preparing the boat, Tsakiris visited us. He took a look at the boat and with a sense of bewilderment, said: “Where are you going with this karidotsouflo[2]?” And then, casting another pitiful glance at our tiny boat, he said: “There is a boat at Thorikon, a short distance north from here, she is going to Crete and needs a crew.”

The first leg (Athens-Turkey) of the road to Alexandria

The boat’s name was ANEMONE. She was a scarcely seaworthy coal burning tramp which before the German invasion used to ply the waters between Piraeus and Salamina.

Her skipper, "Kapetan Anargiros," was a rough-hewn old salt with a great hooked beak of a nose. A rather shrewd individual whose last name we never learned nor did we learn where he was from.

The rest of the crew consisted of: Bosum (Lostromos[3]), an old man who was also the “engineer,” a cook, and Aris, the fireman. Kapetan Anargyros welcomed us aboard and he did not ask for a fare. Of course, four young men, and naval cadets at that, were a godsend to Kapetan Anargyros ! However, Mimis being the youngest and not a cadet was assigned to work with Aris, shoveling coal into the boiler's furnace!

It was about noon when we arrived and as soon as we settled in the boat we heard the air-raid sirens from the nearby town of Lavrion. We ran out and hid in a ditch while Stuka dive-bombers were flying low strafing whatever was moving or whatever was an easy target. Luckily nobody was hurt, including ANEMONE.

Her skipper, "Kapetan Anargiros," was a rough-hewn old salt with a great hooked beak of a nose. A rather shrewd individual whose last name we never learned nor did we learn where he was from.

The rest of the crew consisted of: Bosum (Lostromos[3]), an old man who was also the “engineer,” a cook, and Aris, the fireman. Kapetan Anargyros welcomed us aboard and he did not ask for a fare. Of course, four young men, and naval cadets at that, were a godsend to Kapetan Anargyros ! However, Mimis being the youngest and not a cadet was assigned to work with Aris, shoveling coal into the boiler's furnace!

It was about noon when we arrived and as soon as we settled in the boat we heard the air-raid sirens from the nearby town of Lavrion. We ran out and hid in a ditch while Stuka dive-bombers were flying low strafing whatever was moving or whatever was an easy target. Luckily nobody was hurt, including ANEMONE.

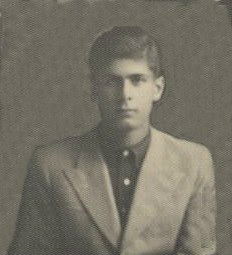

Mimis, 1941

Mimis, 1941

Mimis wrote in his diary: ---------------------------------------------

While the boat was getting ready, the cook prepared a meat-dish for dinner that needed to be baked. Of course, we did not ask and Kapetan Anagyros did not tell where and how he had procured such a "priceless" and rare, under the circumstances, commodity. Being the youngest man on board, I was assigned the unenviable task of taking the baking pan with the prepared meat in it to the local bakery to be baked. I was also given a damijan (a wicker & glass wine bottle) to bring back wine.

On my way to the bakery, I suddenly found myself in the midst of an aerial attack: I heard sirens and the rat-a-tat of gunfire. Glancing over my shoulder I saw bullets exploding in an irregular pattern on the ground as two Stuka planes roared over my head. Only then did I realized that I was the only one on the street. Not being interested in finding out whether the pilots intended to kill me or just scare me, I jumped, with the pan and the damijan, in a ditch for cover. Miraculously, the meat stayed in the pan and the damijan did not break! Once the planes were gone, I resumed going to the bakery and from there to the nearby tavern to buy the wine. We had a good dinner that night--perhaps, the best diner we have had for a long time afterwards. ----------------------------------------------------------

While the boat was getting ready, the cook prepared a meat-dish for dinner that needed to be baked. Of course, we did not ask and Kapetan Anagyros did not tell where and how he had procured such a "priceless" and rare, under the circumstances, commodity. Being the youngest man on board, I was assigned the unenviable task of taking the baking pan with the prepared meat in it to the local bakery to be baked. I was also given a damijan (a wicker & glass wine bottle) to bring back wine.

On my way to the bakery, I suddenly found myself in the midst of an aerial attack: I heard sirens and the rat-a-tat of gunfire. Glancing over my shoulder I saw bullets exploding in an irregular pattern on the ground as two Stuka planes roared over my head. Only then did I realized that I was the only one on the street. Not being interested in finding out whether the pilots intended to kill me or just scare me, I jumped, with the pan and the damijan, in a ditch for cover. Miraculously, the meat stayed in the pan and the damijan did not break! Once the planes were gone, I resumed going to the bakery and from there to the nearby tavern to buy the wine. We had a good dinner that night--perhaps, the best diner we have had for a long time afterwards. ----------------------------------------------------------

Mimis

In the evening we weighed anchor and ventured forth. The general plan was to sail south to Crete, avoiding the open sea for fear of the Luftwaffe, the German air force. At first, we would sail toward the island of Andros and then turn south to stay close to Tinos. From Tinos, we would head south hugging the coastline of the other islands for protection, and from Santorini make a nighttime dash for Crete.

The plan was perfect! But around midnight the engine died. We kept going by jump-starting her, several times. Sometime during the night, Mimis took a break from stoking coal and came up on the deck for some fresh air. While lying on the deck looking at the sky he noticed that the stars were not where they should be! As a Boy Scout, he had acquired an interest in, and a basic knowledge of, astronomy. After identifying the North Star he became a bit concerned, so he went up to the wheel-house. He pointed out to Kapetan Anargiros that our direction of travel did not agree with the geography and the North Star. Kapetan Anargiros unceremoniously dismissed Mimis and his observations with a sneer and a rather rude admonition to mind his [expletive] business, shoveling coal.

At dawn, we, that is Kapetan Anargyros, realized that we had sailed toward the island of Andros instead of Tinos. We had to turn around and follow the course Mimis had suggested! Of course, nobody dared to mention to Kapetan Anargyros that Mimis was right! Finally, we arrived in Tinos around noon where to our astonishment we heard--there was no radio on the ANEMONE--the radio in Athens broadcasting in German news full of sinking ships, downed planes, air raids, occupied towns, scares and, of course, rumors, lies and dire warnings.

We stayed in Tinos several days to repair the engine. Meanwhile, we learned that the waters to the south toward Crete were patrolled by the Italians. So, sailing east was our only option. The new plan called for sailing toward Turkey, a neutral country during the war, and then sail parallel to the Turkish coastline all the way down to its southernmost point. From there we would cut across to Cypress where the British would give us refuge and transportation to Alexandria. Another "perfect" plan, so we thought! So, with no further delay, we set sail for the island of Samos which was still free and very close to Turkey.

The sky was gray and foreboding, Kapetan Anargyros gave the order and ANEMONE lunged toward the open sea battling brutal winds and enormous waves. The wind keening like professional wailers in an Argive funeral, the waves higher than church steeples, and all of us sure we were about to meet our maker. Only God knows how we survived those grueling nights and days with practically nothing to eat or drink.

Wet, hungry, and exhausted we finally arrived in Vathi, the main port of Samos, the birthplace of Pythagoras, and anchored outside the harbor—in the most unlikely place, off of a remote and unprotected promontory on Vathi's northern shore to avoid unnecessary scrutiny by the locals. Unfortunately, ANEMONE's engine died for good this time, leaving us stranded while rumors about an imminent Italian invasion of the island were growing by the hour.

In the harbor lay in anchor a beautiful requisitioned 70-meter sailing yacht, with a good engine, assigned to the Greek Naval Commandant of Samos. But to us it looked like a tremendous waste of a good means of transportation, and before long "absurdity" prevailed! Since the Greek Government did not exist anymore, we opined, we could and should "requisition" the yacht for our trip, and if need be, by force! Ah, the follies of youth!!!

In an attempt to befriend the ship's crew and gain their cooperation, the Commandant, Commander E. Georgoulopoulos, got wind of our plans. And before we had time to think about the logistics of our impending piracy we were hauled in for what amounted to a captain’s mast. Commander Georgoulopoulos was apoplectic with rage at our audacity. We stood in attention, ashen faced, as he was pacing back-and-fort delivering a brutal dressing-down. Then he ran a quick hand over his wispy hair, while staring at us, and shook his head. We took that as a clear indication that he did not like being forced to deal with this problem and as a portent of doom for our escape-to-Alexandria adventure--coming to an imminent and ignominious end. Then with a stern “If you are caught within 50-meters of my ship, I’ll throw you in the brig,” he dismissed us!

With an emphatic but subdued "yessir," we did an about-face and started marching out, as inconspicuously as possible (σαν βρεγμενες γατες!) trying to get out before he changed his mind. But, God bless his soul, as we were clearing the threshold of his office we heard him saying in a soft tone of voice "Godspeed, brave young men!" (“Ο Θεος μαζυ σας, λεβεντες!”). "Thank you, sir," we replied in unison without missing a step in our rush to get out!

Relieved, happy, and exuberant we felt like invincible superheroes. We strutted toward the ladder to disembark with that unwarranted arrogance of those who have faced God's wrath and have come out unscathed, casting disdainful looks at the ship's company who had assembled to mock and see us "hang." And once on terra firma, that uncalled for aura of invincibility took over us, bantering and patting ourselves on the back for our ... stupidity? However, it did not take long before reality set in. Another of our "perfect" plans had failed, and we were not any closer to Alexandria than the day before. Moreover, with limited funds and no immediate answers to our mounting problems, we humbly retreated to the safety of ANEMONI and to Kapetan Anargyros' generous hospitality to eat, relax, and think about our next move.

Alas, we did not have much time to relax or to think about our next move. Events forced upon us our next move! Around the 3rd or 4th of May, the rumors in the streets of Vathi were that the Italians were arriving the next day to occupy the island. Therefore, there was no time for us to waste. We could not risk becoming prisoners of war, or worse yet, be executed as enemy combatants. We had to get out of the island. Our only escape route, now, was through Turkey. That evening we bade farewell to Kapitan Anargyros and his ANEMONE and left on foot under cover of night for Tigani, the present day Pythagoreion. It is an ancient fortified port with Greek and Roman monuments and a spectacular tunnel-aqueduct, and the nearest point to Turkey. We were hoping to find food and enough boats there to make the crossing to Turkey because our small group of four had by now grown to thirty; twenty sailors and a few civilians.

The plan was perfect! But around midnight the engine died. We kept going by jump-starting her, several times. Sometime during the night, Mimis took a break from stoking coal and came up on the deck for some fresh air. While lying on the deck looking at the sky he noticed that the stars were not where they should be! As a Boy Scout, he had acquired an interest in, and a basic knowledge of, astronomy. After identifying the North Star he became a bit concerned, so he went up to the wheel-house. He pointed out to Kapetan Anargiros that our direction of travel did not agree with the geography and the North Star. Kapetan Anargiros unceremoniously dismissed Mimis and his observations with a sneer and a rather rude admonition to mind his [expletive] business, shoveling coal.

At dawn, we, that is Kapetan Anargyros, realized that we had sailed toward the island of Andros instead of Tinos. We had to turn around and follow the course Mimis had suggested! Of course, nobody dared to mention to Kapetan Anargyros that Mimis was right! Finally, we arrived in Tinos around noon where to our astonishment we heard--there was no radio on the ANEMONE--the radio in Athens broadcasting in German news full of sinking ships, downed planes, air raids, occupied towns, scares and, of course, rumors, lies and dire warnings.

We stayed in Tinos several days to repair the engine. Meanwhile, we learned that the waters to the south toward Crete were patrolled by the Italians. So, sailing east was our only option. The new plan called for sailing toward Turkey, a neutral country during the war, and then sail parallel to the Turkish coastline all the way down to its southernmost point. From there we would cut across to Cypress where the British would give us refuge and transportation to Alexandria. Another "perfect" plan, so we thought! So, with no further delay, we set sail for the island of Samos which was still free and very close to Turkey.

The sky was gray and foreboding, Kapetan Anargyros gave the order and ANEMONE lunged toward the open sea battling brutal winds and enormous waves. The wind keening like professional wailers in an Argive funeral, the waves higher than church steeples, and all of us sure we were about to meet our maker. Only God knows how we survived those grueling nights and days with practically nothing to eat or drink.

Wet, hungry, and exhausted we finally arrived in Vathi, the main port of Samos, the birthplace of Pythagoras, and anchored outside the harbor—in the most unlikely place, off of a remote and unprotected promontory on Vathi's northern shore to avoid unnecessary scrutiny by the locals. Unfortunately, ANEMONE's engine died for good this time, leaving us stranded while rumors about an imminent Italian invasion of the island were growing by the hour.

In the harbor lay in anchor a beautiful requisitioned 70-meter sailing yacht, with a good engine, assigned to the Greek Naval Commandant of Samos. But to us it looked like a tremendous waste of a good means of transportation, and before long "absurdity" prevailed! Since the Greek Government did not exist anymore, we opined, we could and should "requisition" the yacht for our trip, and if need be, by force! Ah, the follies of youth!!!

In an attempt to befriend the ship's crew and gain their cooperation, the Commandant, Commander E. Georgoulopoulos, got wind of our plans. And before we had time to think about the logistics of our impending piracy we were hauled in for what amounted to a captain’s mast. Commander Georgoulopoulos was apoplectic with rage at our audacity. We stood in attention, ashen faced, as he was pacing back-and-fort delivering a brutal dressing-down. Then he ran a quick hand over his wispy hair, while staring at us, and shook his head. We took that as a clear indication that he did not like being forced to deal with this problem and as a portent of doom for our escape-to-Alexandria adventure--coming to an imminent and ignominious end. Then with a stern “If you are caught within 50-meters of my ship, I’ll throw you in the brig,” he dismissed us!

With an emphatic but subdued "yessir," we did an about-face and started marching out, as inconspicuously as possible (σαν βρεγμενες γατες!) trying to get out before he changed his mind. But, God bless his soul, as we were clearing the threshold of his office we heard him saying in a soft tone of voice "Godspeed, brave young men!" (“Ο Θεος μαζυ σας, λεβεντες!”). "Thank you, sir," we replied in unison without missing a step in our rush to get out!

Relieved, happy, and exuberant we felt like invincible superheroes. We strutted toward the ladder to disembark with that unwarranted arrogance of those who have faced God's wrath and have come out unscathed, casting disdainful looks at the ship's company who had assembled to mock and see us "hang." And once on terra firma, that uncalled for aura of invincibility took over us, bantering and patting ourselves on the back for our ... stupidity? However, it did not take long before reality set in. Another of our "perfect" plans had failed, and we were not any closer to Alexandria than the day before. Moreover, with limited funds and no immediate answers to our mounting problems, we humbly retreated to the safety of ANEMONI and to Kapetan Anargyros' generous hospitality to eat, relax, and think about our next move.

Alas, we did not have much time to relax or to think about our next move. Events forced upon us our next move! Around the 3rd or 4th of May, the rumors in the streets of Vathi were that the Italians were arriving the next day to occupy the island. Therefore, there was no time for us to waste. We could not risk becoming prisoners of war, or worse yet, be executed as enemy combatants. We had to get out of the island. Our only escape route, now, was through Turkey. That evening we bade farewell to Kapitan Anargyros and his ANEMONE and left on foot under cover of night for Tigani, the present day Pythagoreion. It is an ancient fortified port with Greek and Roman monuments and a spectacular tunnel-aqueduct, and the nearest point to Turkey. We were hoping to find food and enough boats there to make the crossing to Turkey because our small group of four had by now grown to thirty; twenty sailors and a few civilians.

Vathi --> Tigani --> Kusadasi

Vathi --> Tigani --> Kusadasi

The escape to Tigani was exhausting, to say the least. Very much like a Bataan death-march—minus the guards with long bayonets prodding us. The group picked up its way slowly moving with long and fast strides while tilted forward at the waist to counterbalance the weight of our sailor's sack which we were carrying on our back containing all our earthly belongings. Once out of the town, we began to run in the dark on primitive roads and rough terrain across ravines and through boulders to make it to Turkey before daybreak.

Visibility was practically zero and the cold moist air dreadful. Before long, we began discarding personal items to make our load lighter, but it did not help much. Costas, after he had discarded most of his belongings, began to fall behind. Shortly after he stopped, fell to the ground exhausted and announced that he could not go any farther. I talked to him and finally convinced him to continue, pulling him by the hand for the rest of the way—but soon the fatigue of the journey vanished by the promise of its end!

[Author's note: Konstantinos “Costas” Notaras was a life-long friend of Christos' and Mimi's'. I remember having met Costas in one of those family name-day celebrations. In that particular event, for some reason, Christos, Costas, Mimis, and my father were all wearing their navy blue uniform. I, being the youngest in the festivity and impervious of the hot issues of the day, entertained myself trying to count the stripes on their sleeves. But as they moved around I would lose count and I would have to start all over. And to further complicate my "counting," there was Stelios Malandrakis, Christos' paternal cousin and future army General, wearing a "strange" olive-green (army) uniform without stripes on his sleeves but a silver (lieutenant's) star on his epaulets—simple things entertain simple minds!]

When we finally arrived in Tigani, we boarded several fishing boats whose owners not only volunteered to take us across but they also fed us from their meager food supply. God bless their souls for their generosity—we were tired, thirsty, and very hungry!

At daybreak, our little "armada" approached Tsagli, the nearest point to Turkey from Samos. Had our luck finally turned? Everything was quiet, the sun just breaking the rim of the sea, and no one had spotted us as we were furiously rowing the last few hundred yards to the shore.

"Look, look! There's something odd up there," someone shouts from aft, pointing. All heads instantly turned that direction. Indeed, there was a structure like the tower of a fortress. Looking at it, I felt a chill as if I had seen the devil. The sight of it made me suck in a deep breath of the cold moist air that made my lungs hurt. And before I had time to process my thoughts I saw a red flag with the crescent moon unfurling at the top of it followed by gun flashes and the unmistakable sound of rifle shots. The Turkish shore garrison was firing at us despite the fact that we were shouting at them that we were Greeks fleeing from the German-occupied Greece. At long last, the gunfire dribbled off to scattered individual shots, and for all the effect they wrought, might as well have fired in salute of our escape!

After that "warm" reception we turned a bit to the north, rowing as fast as we could to avoid casualties. "The bastards," someone swore half under his breath, "They are launching a boat." I turned to look, and I froze for a few seconds trying to make sense of what I was seeing. I saw the number of men in grey uniforms at the seashore and around the building to have grown into a small army. It took me an agonizingly long time to sort out what was going on out there.

"Where is it ?" I asked, nobody in particular. "I don't see any boat," I said.

"We are in trouble, ah," said the same voice who supposedly had seen a boat being launched.

"What do you mean?" I said while pulling the oars even faster.

"Relax, there is no boat" I said, turning my head toward the shore to make sure.

"Won't they chase us?" He asked.

"Oh, shut up and keep rowing," I said. "If they were going to attack us, a patrol boat would already have intercepted us," I said in a loud voice so all in the boat could hear.

No one said a word. We all understood our lives hung in the balance of countless factors, most of which were totally out of our control. We kept rowing hopping for the best. After a couple of hours steady on the course, we eventually disembarked around 11:00 am on May 3 or 4, 1941 in Kusadasi, Turkey.

Kousadasi to Alexandretta

At that time Kusadasi was a small fishing village, on the western Aegean seaboard of Turkey, and not the cosmopolitan Mediterranean cruise-line hub that is today.

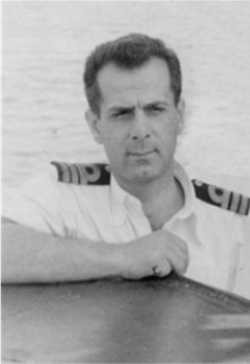

During the war, the Turkish authorities were sending back any and all Greek civilians they would capture, but not military personnel. Costas, Pericles, and I had papers identifying us as naval cadets, but Mimis being a civilian had none. He was at risk of being sent back. Of course, Mimis under no circumstances wanted to go back. He was determined to join the Navy. So he donned a ragtag sailor’s uniform, and that was the humble beginnings of a distinguished naval career.

During the war, the Turkish authorities were sending back any and all Greek civilians they would capture, but not military personnel. Costas, Pericles, and I had papers identifying us as naval cadets, but Mimis being a civilian had none. He was at risk of being sent back. Of course, Mimis under no circumstances wanted to go back. He was determined to join the Navy. So he donned a ragtag sailor’s uniform, and that was the humble beginnings of a distinguished naval career.

Christos' Dagger

Christos' Dagger

Unshaven, dirty, hungry, thirsty, and exhausted after so many hours of sleepless physical exertion, landing in Kusadasi was a bittersweet relief. The most difficult part of our trip, or so we thought, was behind us, but so was our beloved country.

As we took our first steps on Turkish soil, the four of us, turned towards the sea and with teary eyes bade Greece "until we see you again" ("εις το επανιδείν"). We stood there in a trance for a while, channeling home and our loved ones. Then, blinking back tears and being mutually embarrassed for our sentimentality, we turned and walked away to join the rest of the group resorting into sarcasm, banter, and flippancy: "Let's see what the Turks have in store for us!" I said huskily. "They'll teach us how to say 'Long live Churchill' in Turkish," Costas retorted! We laughed, relieved that we were back to our normal selves again.

Naturally, our arrival in such a small place did not go unnoticed. No sooner than we had gotten out of the boats than the law appeared in the person of a portly, heavily mustachioed Turkish constable followed by several armed soldiers. Surprisingly, he looked more pleased than concerned about the legalities of a few boatloads of Greek refugees landing at his shore. He authoritatively asked for our "papers!" After he collected a handful, some with colorful stamps and French text that it is doubtful he understood, took a few steps away from us pretending that he was making sense out of the documents, while glancing at us with predatory eyes of an inquisitor. The more time he was taking to examine the papers the more we were getting acclimated to the idea of a bribe being afoot. Or to put it in more polite terms, paying some preposterous "landing fees" that he might have concocted.

Glad to say, we were badly mistaken! He did not ask for a bribe or any contrived fees! He simply started writing our names on a piece of paper as he was returning our documents, while one of his soldiers laid a blanket on the ground. Then he ordered us to surrender (throw in the blanket) everything we owned, except the clothes we were wearing. With extreme trepidation, we complied, emptying our pockets and Duffle bags. Money, rings, amulets, key chains, cigarette lighters, and gold baptismal-necklace-crucifixes piled up on the blanket. As he supposedly was recording what each person was throwing down, he informed us that we would get them back when we leave Turkey. Needless to say that we never saw any of our belongings again. There is where I "lost," among other things, my Cadet's Dagger (a small sword, part of the Cadet's uniform), something that I still miss very much!

With the "customs" business completed, the constable took his loot and wandered off to make his report, I presume to someone with the rank to make a decision about us, and to split the goods with. But that was not the only thing we lost in Kusadasi. Our buddy Pericles also disappeared! His mother was sister (?) of General D. Drakos, the Inspector General of the Greek Army. So we surmised that our Military attache in Ankara, either by his own initiative or by special request (?) pulled Pericles out. However, we met up with him again in Alexandria.

As we took our first steps on Turkish soil, the four of us, turned towards the sea and with teary eyes bade Greece "until we see you again" ("εις το επανιδείν"). We stood there in a trance for a while, channeling home and our loved ones. Then, blinking back tears and being mutually embarrassed for our sentimentality, we turned and walked away to join the rest of the group resorting into sarcasm, banter, and flippancy: "Let's see what the Turks have in store for us!" I said huskily. "They'll teach us how to say 'Long live Churchill' in Turkish," Costas retorted! We laughed, relieved that we were back to our normal selves again.

Naturally, our arrival in such a small place did not go unnoticed. No sooner than we had gotten out of the boats than the law appeared in the person of a portly, heavily mustachioed Turkish constable followed by several armed soldiers. Surprisingly, he looked more pleased than concerned about the legalities of a few boatloads of Greek refugees landing at his shore. He authoritatively asked for our "papers!" After he collected a handful, some with colorful stamps and French text that it is doubtful he understood, took a few steps away from us pretending that he was making sense out of the documents, while glancing at us with predatory eyes of an inquisitor. The more time he was taking to examine the papers the more we were getting acclimated to the idea of a bribe being afoot. Or to put it in more polite terms, paying some preposterous "landing fees" that he might have concocted.

Glad to say, we were badly mistaken! He did not ask for a bribe or any contrived fees! He simply started writing our names on a piece of paper as he was returning our documents, while one of his soldiers laid a blanket on the ground. Then he ordered us to surrender (throw in the blanket) everything we owned, except the clothes we were wearing. With extreme trepidation, we complied, emptying our pockets and Duffle bags. Money, rings, amulets, key chains, cigarette lighters, and gold baptismal-necklace-crucifixes piled up on the blanket. As he supposedly was recording what each person was throwing down, he informed us that we would get them back when we leave Turkey. Needless to say that we never saw any of our belongings again. There is where I "lost," among other things, my Cadet's Dagger (a small sword, part of the Cadet's uniform), something that I still miss very much!

With the "customs" business completed, the constable took his loot and wandered off to make his report, I presume to someone with the rank to make a decision about us, and to split the goods with. But that was not the only thing we lost in Kusadasi. Our buddy Pericles also disappeared! His mother was sister (?) of General D. Drakos, the Inspector General of the Greek Army. So we surmised that our Military attache in Ankara, either by his own initiative or by special request (?) pulled Pericles out. However, we met up with him again in Alexandria.

Christos

At noon, a Kusadasi resident, perhaps under orders from the looter, who most likely was the local chief of police, took the three of us to his house. He was speaking fluent Greek and showed us great hospitality. I immediately noticed that he was speaking Greek with a Cretan accent! When I asked him about it he said that he was a Turkish-Cretan. So, when I let him know that Mimis and I were Cretans he was moved to tears and said that he considered us as compatriots.

We stayed at his house until late afternoon when a low-ranking local functionary showed up telling us to go to a certain gathering place for transfer, with some rickety trucks, to Smyrna.

In Smyrna we were housed in the officers' quarters of a regimental camp, six men per room and we were fed in the officers' mess. It was fortunate that in Kusadasi the Turkish constable, who stole my Dagger, registered Mimis as a "Cadet." From that point on the various Turkish authorities were placing Mimis with us. We stayed two days in Smyrna before being transported to Pergamos. The attitude of the Turks toward us was rather friendly. We were not restricted in our movements inside the camp, but we were not allowed to go outside except by special permission.

Two days later they moved us to Pergamos. We were housed in a special military camp for Greeks who had fled from Greece. Among others, there was a whole Greek Brigade, about 1,500 men, the so-called "Brigade of Evros." Upon collapse of the Greek front, the Brigade crossed over to neutral Turkey where the Turks, according to International Law, disarmed them and divided them into two groups: those who wanted to return to Greece and those who did not. The two groups were housed separately and were not allowed to have any communications with each other.

I will never forget a scene of utter cruelty I witnessed one day as we were getting out of the camp. It gave me a harrowing picture of the Turkish officer vis-a-vis the Turkish soldier and the Turkish civilian. An old man was passing by the camp gate. He stopped and began chatting with the guard. A Turkish officer who was walking behind us noticed the exchange, he ran past us and viciously attacked the old man punching, shoving, and kicking him. Then he turned toward the guard, who was standing at attention, lifted the guard's helmet and proceeded to savagely punch him repeatedly in the face with his clenched fist. When the officer left we saw the guard crying in mute silence. Needless to say, we tried to get far away fast and as inconspicuously as possible.

Besides the three of us, there were about sixty other navy men in the camp. And although the camp buildings were old and decrepit, for us, being officers, life was not that bad. Among the other privileges, we were allowed to leave the camp for a few hours every day. In one of those outings, we heard extremely worrying stories about the (German) Occupation of Athens and the Battle of Crete. Another thing I remember vividly from our visits to the town was that the women we passed, covered in shapeless robes. If they were not veiled, they would cover their faces to protect themselves from the pestilence of our gaze. And, if they passed by us, while we were killing time drinking tea in a "Kafenio," they would look the other way. Or if they were on a horse-drawn cart on their way to the fields, they would drop to the floor so we would not see their face!

On the way to the coffee house (Kafenio), we would pass by an open-air market, a bazaar, where everything was for sale, and I mean everything! Besides burka/niqab/hijab shrouded women, shouting merchants, flies, braying donkeys, more flies, snorting camels, and begging street urchins, there were spices, pigs, figs, grain, oil, butchered animal parts (I hope), dead and live chickens, raptors hooded and tied to poles, hookah pipes, hashish, incense, ornate brass cookware, necklaces and pendants, faux jewellery encrusted daggers, leather goods, and all sorts of fish, meat, and eatables of questionable quality or freshness.

Nevertheless, some of the merchandise was exquisitely ornate, inexpensive, and hard to resist. Several times I came very close to splurge on a beautiful real-leather "sac de voyage" to replace my old navy-issued sailor's sac. But realizing that I was lacking in "bazaar-haggling" expertise I kept postponing the purchase for the next time. A rather disappointing realization which fortunately turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

One evening, a Second Lieutenant from the "Evros Brigade" we had befriended, came around enthusiastically showing us the treasure he had bought: A leather sac like the one I was infatuated with, at a ridiculously low price, haggling at the bazaar! Pangs of self-resentment for my procrastination hit me. I feigned enthusiasm and vowed to myself to buy one the next day, haggling or no-haggling!

I had hardly slept that night, practicing in my head "haggling" scenarios, when I was rudely awakened early in the morning by a big noisy commotion that had broken out in the Second Lieutenant's ward. He had made the mistake of washing the sack and hanging it out overnight to dry before using it. Apparently, the tanning process of the leather was not done properly, if it was done at all, so the sac shrank and stank to high heaven, sending the occupants of the ward out screaming, cussing, and puking. Needless to say that after I learned what the commotion was all about I could not believe my eyes how beautiful my old sailor's sack looked!

Meanwhile, the Germans were pressuring the Turks to either send the Greeks back to Greece or to keep them in Turkey for the duration of the war. One day the German Ambassador from Ankara, von Papen, visited the camp, presumably to inspect the camps' security. Regardless of the intent of his visit, this did not bode well for us whose plan was to join our fleet in Alexandria. We started planning to escape with three other officers from the "Evros Brigade", but we concluded that the best plan was to wait for further developments.

Luckily, toward the end of May, we were told that all of us who had declared that we did not want to return to Greece would be moved to some other place. Meanwhile, truckloads of cheap civilian clothes arrived and were distributed to all detainees, including us.

On May 29, we were ordered to put on our newly acquired civvies and get ready for transport. As we were gathering to get on the trucks, wearing this hodgepodge of clothing, we looked like being dressed for a Halloween party! They also gave us 30 Turkish Liras and we were sent on our way. Later we learned that the cloths and the money were made available to us thanks to funds raised by the Greeks in Constantinople.

We stayed at his house until late afternoon when a low-ranking local functionary showed up telling us to go to a certain gathering place for transfer, with some rickety trucks, to Smyrna.

In Smyrna we were housed in the officers' quarters of a regimental camp, six men per room and we were fed in the officers' mess. It was fortunate that in Kusadasi the Turkish constable, who stole my Dagger, registered Mimis as a "Cadet." From that point on the various Turkish authorities were placing Mimis with us. We stayed two days in Smyrna before being transported to Pergamos. The attitude of the Turks toward us was rather friendly. We were not restricted in our movements inside the camp, but we were not allowed to go outside except by special permission.

Two days later they moved us to Pergamos. We were housed in a special military camp for Greeks who had fled from Greece. Among others, there was a whole Greek Brigade, about 1,500 men, the so-called "Brigade of Evros." Upon collapse of the Greek front, the Brigade crossed over to neutral Turkey where the Turks, according to International Law, disarmed them and divided them into two groups: those who wanted to return to Greece and those who did not. The two groups were housed separately and were not allowed to have any communications with each other.

I will never forget a scene of utter cruelty I witnessed one day as we were getting out of the camp. It gave me a harrowing picture of the Turkish officer vis-a-vis the Turkish soldier and the Turkish civilian. An old man was passing by the camp gate. He stopped and began chatting with the guard. A Turkish officer who was walking behind us noticed the exchange, he ran past us and viciously attacked the old man punching, shoving, and kicking him. Then he turned toward the guard, who was standing at attention, lifted the guard's helmet and proceeded to savagely punch him repeatedly in the face with his clenched fist. When the officer left we saw the guard crying in mute silence. Needless to say, we tried to get far away fast and as inconspicuously as possible.

Besides the three of us, there were about sixty other navy men in the camp. And although the camp buildings were old and decrepit, for us, being officers, life was not that bad. Among the other privileges, we were allowed to leave the camp for a few hours every day. In one of those outings, we heard extremely worrying stories about the (German) Occupation of Athens and the Battle of Crete. Another thing I remember vividly from our visits to the town was that the women we passed, covered in shapeless robes. If they were not veiled, they would cover their faces to protect themselves from the pestilence of our gaze. And, if they passed by us, while we were killing time drinking tea in a "Kafenio," they would look the other way. Or if they were on a horse-drawn cart on their way to the fields, they would drop to the floor so we would not see their face!

On the way to the coffee house (Kafenio), we would pass by an open-air market, a bazaar, where everything was for sale, and I mean everything! Besides burka/niqab/hijab shrouded women, shouting merchants, flies, braying donkeys, more flies, snorting camels, and begging street urchins, there were spices, pigs, figs, grain, oil, butchered animal parts (I hope), dead and live chickens, raptors hooded and tied to poles, hookah pipes, hashish, incense, ornate brass cookware, necklaces and pendants, faux jewellery encrusted daggers, leather goods, and all sorts of fish, meat, and eatables of questionable quality or freshness.

Nevertheless, some of the merchandise was exquisitely ornate, inexpensive, and hard to resist. Several times I came very close to splurge on a beautiful real-leather "sac de voyage" to replace my old navy-issued sailor's sac. But realizing that I was lacking in "bazaar-haggling" expertise I kept postponing the purchase for the next time. A rather disappointing realization which fortunately turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

One evening, a Second Lieutenant from the "Evros Brigade" we had befriended, came around enthusiastically showing us the treasure he had bought: A leather sac like the one I was infatuated with, at a ridiculously low price, haggling at the bazaar! Pangs of self-resentment for my procrastination hit me. I feigned enthusiasm and vowed to myself to buy one the next day, haggling or no-haggling!

I had hardly slept that night, practicing in my head "haggling" scenarios, when I was rudely awakened early in the morning by a big noisy commotion that had broken out in the Second Lieutenant's ward. He had made the mistake of washing the sack and hanging it out overnight to dry before using it. Apparently, the tanning process of the leather was not done properly, if it was done at all, so the sac shrank and stank to high heaven, sending the occupants of the ward out screaming, cussing, and puking. Needless to say that after I learned what the commotion was all about I could not believe my eyes how beautiful my old sailor's sack looked!

Meanwhile, the Germans were pressuring the Turks to either send the Greeks back to Greece or to keep them in Turkey for the duration of the war. One day the German Ambassador from Ankara, von Papen, visited the camp, presumably to inspect the camps' security. Regardless of the intent of his visit, this did not bode well for us whose plan was to join our fleet in Alexandria. We started planning to escape with three other officers from the "Evros Brigade", but we concluded that the best plan was to wait for further developments.

Luckily, toward the end of May, we were told that all of us who had declared that we did not want to return to Greece would be moved to some other place. Meanwhile, truckloads of cheap civilian clothes arrived and were distributed to all detainees, including us.

On May 29, we were ordered to put on our newly acquired civvies and get ready for transport. As we were gathering to get on the trucks, wearing this hodgepodge of clothing, we looked like being dressed for a Halloween party! They also gave us 30 Turkish Liras and we were sent on our way. Later we learned that the cloths and the money were made available to us thanks to funds raised by the Greeks in Constantinople.

Mimis

They transported us to the railroad station in a nearby town, Soma, east of Aivali. They loaded us and what had been left of our meager belongings on a train, in boxcars designed for transporting cattle and horses—a painted sign at the door of the cars read " Men: 40, Horses: 8." The guards came by, counted twenty-one of us, shut the car's door tight, and our journey to "destination unknown" began. But before long the train came to an abrupt halt. It stayed motionless for hours, heat and tempers rising inside the car with so many men packed in and nothing to do. After what seemed like an eternity with a jerk the train crept forward. Our journey begun supposedly to somewhere near the south border of Turkey.

The trip lasted about eight tortuous days. And depending on the time of the day or the locale, conditions inside the car were either stifling or bone-chilling, or both—comparable to that epic train ride through the Ural Mountains in the movie "Dr. Zhivago. "

The food, such as it was, was the rations of dry food they had given us before our departure. Occasionally, when the train would stop at a siding to let another train go through, they would let us out to stretch our legs and do some housekeeping, under the watchful eyes of our guards. Also, they would give us a couple of slices of bread each and a thin soup made with potatoes or cabbage, hardly enough calories for the exertion of the arduous journey and the calories spent shivering during the Anatolian freezing Spring nights. We slept on the floor, in our clothes, on makeshift mattresses made with straw from a pile in a corner of the car. Also, each car was provided with a jug of water, which we had to ration very carefully because refills were made at irregular time intervals, and a bucket to serve as the toilet. In the crowded quarters of the car, the only privacy we had while taking care of our physical needs was provided by the tattered remains of what used to be a rug hung between the two sides of the car—servicemen have no false modesty—in the opposite corner from where the water jug and the straw pile were.

Besides the inconvenience of having to wait for your turn to use the bucket, it was a huge challenge, especially at night, having to navigate among the stretched out bodies on the floor to get to it. And the challenge was even bigger trying to find your way back to your pile of straw (bed?) in the dimness of a hurricane oil lamp hanging from the ceiling. Needless to say that there was a horrid stench emanating from the bucket which, combined with the obnoxious odor of human sweat, was constantly assaulting our nostrils, even when the door was slid open the few inches its locking mechanism would allow. But most debilitating of all was the lack of any meaningful way to pass those endless hours being cooped up in a stinking boxcar and the nauseating ritual of emptying the bucket, especially when the train was moving. To break the boredom we were playing dice. Thus, those thirty Turkish-Liras changed hands many times during the trip!

I remember Mimis telling me that "Don Juan" was singled out and not allowed to depart with the rest of us. We had met this slightly comical figure while in Pergamos. He had claimed to have been a Spanish air force pilot. He even had the requisite goggles and the scarf to prove it. He had made it known that he was on the Democratic side of the Spanish Civil War (1934-1936), an opponent of Franco. He had also claimed to have traveled to Greece to fight the Germans. His full name was Don Juan Alonzo Moreno y Alambra y Confaloniero y Nuestro Juan de Santa Cruz, if I understood him correctly. Besides being concerned about his fate, we were also deeply disappointed not having that colorful character in our group. It was rumored that he ended up in Palestine where he was arrested and hanged, supposedly, for being a spy.

The trip lasted about eight tortuous days. And depending on the time of the day or the locale, conditions inside the car were either stifling or bone-chilling, or both—comparable to that epic train ride through the Ural Mountains in the movie "Dr. Zhivago. "

The food, such as it was, was the rations of dry food they had given us before our departure. Occasionally, when the train would stop at a siding to let another train go through, they would let us out to stretch our legs and do some housekeeping, under the watchful eyes of our guards. Also, they would give us a couple of slices of bread each and a thin soup made with potatoes or cabbage, hardly enough calories for the exertion of the arduous journey and the calories spent shivering during the Anatolian freezing Spring nights. We slept on the floor, in our clothes, on makeshift mattresses made with straw from a pile in a corner of the car. Also, each car was provided with a jug of water, which we had to ration very carefully because refills were made at irregular time intervals, and a bucket to serve as the toilet. In the crowded quarters of the car, the only privacy we had while taking care of our physical needs was provided by the tattered remains of what used to be a rug hung between the two sides of the car—servicemen have no false modesty—in the opposite corner from where the water jug and the straw pile were.

Besides the inconvenience of having to wait for your turn to use the bucket, it was a huge challenge, especially at night, having to navigate among the stretched out bodies on the floor to get to it. And the challenge was even bigger trying to find your way back to your pile of straw (bed?) in the dimness of a hurricane oil lamp hanging from the ceiling. Needless to say that there was a horrid stench emanating from the bucket which, combined with the obnoxious odor of human sweat, was constantly assaulting our nostrils, even when the door was slid open the few inches its locking mechanism would allow. But most debilitating of all was the lack of any meaningful way to pass those endless hours being cooped up in a stinking boxcar and the nauseating ritual of emptying the bucket, especially when the train was moving. To break the boredom we were playing dice. Thus, those thirty Turkish-Liras changed hands many times during the trip!

I remember Mimis telling me that "Don Juan" was singled out and not allowed to depart with the rest of us. We had met this slightly comical figure while in Pergamos. He had claimed to have been a Spanish air force pilot. He even had the requisite goggles and the scarf to prove it. He had made it known that he was on the Democratic side of the Spanish Civil War (1934-1936), an opponent of Franco. He had also claimed to have traveled to Greece to fight the Germans. His full name was Don Juan Alonzo Moreno y Alambra y Confaloniero y Nuestro Juan de Santa Cruz, if I understood him correctly. Besides being concerned about his fate, we were also deeply disappointed not having that colorful character in our group. It was rumored that he ended up in Palestine where he was arrested and hanged, supposedly, for being a spy.

Mimis, Sub Skipper

Mimis, Sub Skipper

Our first real stop was at the Mersina train station, where all of the soldiers guarding us were withdrawn. They were replaced with some civilians for preparing and serving that watery soup for the rest of the trip. While there, Mimis bought a map of Turkey. Knowing the train’s direction of travel, he correctly surmised that we were going toward Alexandretta, at the southeast most corner of Turkey. The city was named after Alexander the Great. Today it is called Iskenderun, for Iskender, Turkish form of Alexander.

In Alexandretta, the three of us (Costas Notaras, Mimis and I) and the other sixty navy men were taken to a British merchant marine vessel named “DURENDA,” [4], a 7,000-ton freighter.

After eight days of miserable existence being cooped up in a box car--the fetid odors of trapped air, foul clothing, urine and human excrement--boarding DURENDA and breathing fresh air was like entering Paradise! And although the accommodations were Spartan, food of regular potato soup supplemented with fresh vegetables and small portions of fish or meat, compared to the food on the train, was like a feast. Also, having access to a real in-door bathroom, take a shower with hot water and soap, and being able to wash the clothes we were wearing for eight days made conditions on board seem luxurious, if not decadent-- certainly a godsend gift!

The ship was loaded with bales of tobacco. Her officers were British and the crew Indian. Also on board were 40-50 Norwegian young men and women. They had escaped on skis from Norway into Russia and from there had traveled overland to Turkey. The Turks, with assistance from the British, got them aboard the DURENDA.

In Alexandretta, the three of us (Costas Notaras, Mimis and I) and the other sixty navy men were taken to a British merchant marine vessel named “DURENDA,” [4], a 7,000-ton freighter.

After eight days of miserable existence being cooped up in a box car--the fetid odors of trapped air, foul clothing, urine and human excrement--boarding DURENDA and breathing fresh air was like entering Paradise! And although the accommodations were Spartan, food of regular potato soup supplemented with fresh vegetables and small portions of fish or meat, compared to the food on the train, was like a feast. Also, having access to a real in-door bathroom, take a shower with hot water and soap, and being able to wash the clothes we were wearing for eight days made conditions on board seem luxurious, if not decadent-- certainly a godsend gift!

The ship was loaded with bales of tobacco. Her officers were British and the crew Indian. Also on board were 40-50 Norwegian young men and women. They had escaped on skis from Norway into Russia and from there had traveled overland to Turkey. The Turks, with assistance from the British, got them aboard the DURENDA.

Durenda. courtesy www.shipsnostalgia.com

DURENDA departed at dusk for Port Said, Egypt. Norwegians and Greeks were placed at opposite corners of a huge compartment in the aft hold of the ship. The Norwegian women were gorgeous blonds, minding their business.

We, however, were beside ourselves; ogling them as young men usually do when they haven't seen a female for weeks. Moreover, the dimness of the hold and the pocks of light forced us to peer even more intently at them. Whether they minded our ogling or not I don't know and we did not care. And if that was not bad enough, our newly found Paradise turned into living hell when the women took off all their clothes to take a shower, in public view, like if they were in the privacy of their own bathroom!

We gaped in shock, puzzlement, and desire. We were lusting after those incredibly beautiful, athletically built, statuesque women sending seductive smiles our way while torrents of blond ringlets were cascading down around their beautiful shoulders as they began to undress and shower. And the only thing we could do, according to Matthew 5:28, was "committing adultery in our heart!"

Needless to say that the commotion among the Greeks was something hard to describe. Saying that we were devouring them with our eyes it is an understatement. Suffice it to say that a sailor, out of frustration, bloodied his head banging it on the bulkhead while spewing "love-filled" obscenities. To this day, the image of those beautiful nude women giggling and gyrating under those makeshift showers is seared into my brain!

The third day, we were attacked by three French planes of the Vichy government that were based in Lebanon. And although DURENDA was an easy target, without antiaircraft guns, she managed to dodge the bombs—no doubt the captain's masterful maneuvering saved us from a direct hit. Of course, we fired back with the side arms they had given us without any effect. Nevertheless, those were our very first shots at the enemy! I saw, Mimis, fearlessly firing at them and although I was concerned about his safety, I was very proud of him.

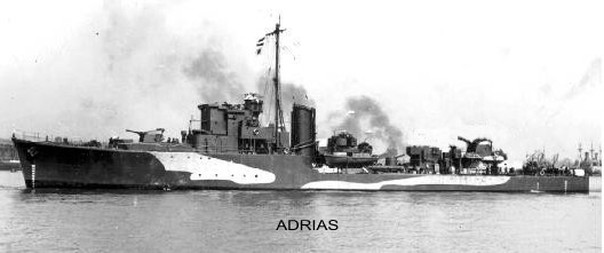

Eventually, a bomb hit the bow hold killing several Indian sailors. Evidently, the bomb was not very powerful or perhaps the bales of tobacco absorbed the shock and kept the ship from immediately sinking. The ship took in water and listed by the head to the point where half of the propeller was out of the water—a dress rehearsal for my ADRIAS experience? Immediately, the race to keep the ship afloat began. With the pumps continuously working, our speed was considerably reduced, and the food reserves were exhausted. We were served soup made out of bones and the leftovers that due to the war conditions we were not allowed to throw overboard as a security precaution to avoid detection.

While limping along, DURENDA entered British protected waters and the bombings stopped. Passengers and crew donned their life jackets and remained at the "ready to board" their assigned lifeboats. The passengers spent the night in the open air next to the lifeboats, while the ship continued moving very slowly.

We, however, were beside ourselves; ogling them as young men usually do when they haven't seen a female for weeks. Moreover, the dimness of the hold and the pocks of light forced us to peer even more intently at them. Whether they minded our ogling or not I don't know and we did not care. And if that was not bad enough, our newly found Paradise turned into living hell when the women took off all their clothes to take a shower, in public view, like if they were in the privacy of their own bathroom!

We gaped in shock, puzzlement, and desire. We were lusting after those incredibly beautiful, athletically built, statuesque women sending seductive smiles our way while torrents of blond ringlets were cascading down around their beautiful shoulders as they began to undress and shower. And the only thing we could do, according to Matthew 5:28, was "committing adultery in our heart!"

Needless to say that the commotion among the Greeks was something hard to describe. Saying that we were devouring them with our eyes it is an understatement. Suffice it to say that a sailor, out of frustration, bloodied his head banging it on the bulkhead while spewing "love-filled" obscenities. To this day, the image of those beautiful nude women giggling and gyrating under those makeshift showers is seared into my brain!

The third day, we were attacked by three French planes of the Vichy government that were based in Lebanon. And although DURENDA was an easy target, without antiaircraft guns, she managed to dodge the bombs—no doubt the captain's masterful maneuvering saved us from a direct hit. Of course, we fired back with the side arms they had given us without any effect. Nevertheless, those were our very first shots at the enemy! I saw, Mimis, fearlessly firing at them and although I was concerned about his safety, I was very proud of him.

Eventually, a bomb hit the bow hold killing several Indian sailors. Evidently, the bomb was not very powerful or perhaps the bales of tobacco absorbed the shock and kept the ship from immediately sinking. The ship took in water and listed by the head to the point where half of the propeller was out of the water—a dress rehearsal for my ADRIAS experience? Immediately, the race to keep the ship afloat began. With the pumps continuously working, our speed was considerably reduced, and the food reserves were exhausted. We were served soup made out of bones and the leftovers that due to the war conditions we were not allowed to throw overboard as a security precaution to avoid detection.

While limping along, DURENDA entered British protected waters and the bombings stopped. Passengers and crew donned their life jackets and remained at the "ready to board" their assigned lifeboats. The passengers spent the night in the open air next to the lifeboats, while the ship continued moving very slowly.

Mimis

The following day, June 9, 1941, between 2:00-3:00 pm, DURENDA arrived in Port Said, Egypt—the entrance to the Suez Canal. As DURENDA moved south into the port, one of the Greek sailors pointed out a Greek warship. From its number, he recognized it as the destroyer AETOS [5]. After all these hours of stress, the Greeks aboard DURENDA flocked to one side of the boat and yelled loudly "Long live Greece!" (“Ζητω η Ελλας.”) The captain of AETOS, Commander Ioannis Toumbas, who was already quite famous in the Greek Navy, heard about it and sent his adjutant to find out who we were and do the necessary security check [6].

Mimis remembers that I immediately recognized the adjutant as my senior by two years in the Academy, Ensign I. Stratakis. Among DURENDA's passengers were four stranded AETOS sailors who had been on leave when AETOS, due to battle orders, had to leave in a hurry leaving them behind.

Ensign Stratakis escorted all six of us, and Mimis, to AETOS. Once Commander Toumbas learned the identity of the "DURENDA 7," as we were dubbed, he communicated with the British legal representative of the region and arranged to take us on board AETOS [5].

Mimis remembers that I immediately recognized the adjutant as my senior by two years in the Academy, Ensign I. Stratakis. Among DURENDA's passengers were four stranded AETOS sailors who had been on leave when AETOS, due to battle orders, had to leave in a hurry leaving them behind.

Ensign Stratakis escorted all six of us, and Mimis, to AETOS. Once Commander Toumbas learned the identity of the "DURENDA 7," as we were dubbed, he communicated with the British legal representative of the region and arranged to take us on board AETOS [5].

AETOS

AETOS

When we were presented to Commander Toumbas aboard AETOS, Mimis, being the youngest of the group and not a member of the navy, stood shyly behind us. Toumbas, who, of course, had been informed of everyone’s identity, greeted us one-by-one and when he got to Mimis, his eyebrows shot upward in make-believe surprise. He paused for a moment, looked at Mimis from head to toe, and said, "And you little shit what are you doing here?" (“και εσυ σκατο τι κανεις εδω?") [7] Mimis, without losing his cool, replied, “I came to enlist as a volunteer, sir," while the rest of us were trying very hard to restrain ourselves from bursting into laughter.

While on board AETOS, convoying merchant ships and hunting U-boats in the Eastern Mediterranean, we were assigned as assistants to the duty officer. After a few trips, AETOS arrived in Alexandria, Egypt. The three cadets, I say three because Toumbas had anointed Mimis "Cadet" on the bridge of AETOS, disembarked and presented ourselves to the Geek Naval authorities.

In 1941 Alexandria was a cosmopolitan port town aswarm with frigates, troop transports and supply ships when we arrived. It was situated in the outer perimeter of the Nile Delta and of great importance to the Allied Navies, that is, to the British. It was the only harbor in the Easter Mediterranean large enough to shelter a fleet in case Malta, that unsinkable British aircraft carrier in Central Mediterranean, were to fall.

Allied soldiers and sailors; foreign communities and spies; upscale neighborhoods for the rich and the high governmental employees; and vibrant casinos and chic salons for the beautiful people and those associated with King Farouk's palace made up the city's upper crust. Whereas its squalid, overcrowded, fly-infested, dust-blown side streets were teeming with beggars, animals, thieving children, and roving vendors of all descriptions pushing or dragging rickety old carts hawking their wares through a gauntlet of cobblers' shops, resplendent parked camels, legless beggars strapped to makeshift "wheelchairs," open-air barber shops whose customers were sitting on colorful discarded produce crates, street dentists—a pair of rusty pliers, no anesthesia, no disinfectant, and no complaints. And shadowy saloons promising every pleasure under the sun, cafes full of hookah-sucking men, and brothels for all purses and predilections. And the air was permeated by a nauseating mixture of tobacco smoke, Turkish coffee aroma, and camel dung stench.

In other words, a typical middle-eastern town of the day and a huge military security and discipline nightmare. And a new and strange experience for young cadets away from home and the civilities of a sheltered, upper-middle-class upbringing we all had in a clean and well-disciplined, under the oppressive Metaxas dictatorship, prewar city like Athens.

While on board AETOS, convoying merchant ships and hunting U-boats in the Eastern Mediterranean, we were assigned as assistants to the duty officer. After a few trips, AETOS arrived in Alexandria, Egypt. The three cadets, I say three because Toumbas had anointed Mimis "Cadet" on the bridge of AETOS, disembarked and presented ourselves to the Geek Naval authorities.

In 1941 Alexandria was a cosmopolitan port town aswarm with frigates, troop transports and supply ships when we arrived. It was situated in the outer perimeter of the Nile Delta and of great importance to the Allied Navies, that is, to the British. It was the only harbor in the Easter Mediterranean large enough to shelter a fleet in case Malta, that unsinkable British aircraft carrier in Central Mediterranean, were to fall.

Allied soldiers and sailors; foreign communities and spies; upscale neighborhoods for the rich and the high governmental employees; and vibrant casinos and chic salons for the beautiful people and those associated with King Farouk's palace made up the city's upper crust. Whereas its squalid, overcrowded, fly-infested, dust-blown side streets were teeming with beggars, animals, thieving children, and roving vendors of all descriptions pushing or dragging rickety old carts hawking their wares through a gauntlet of cobblers' shops, resplendent parked camels, legless beggars strapped to makeshift "wheelchairs," open-air barber shops whose customers were sitting on colorful discarded produce crates, street dentists—a pair of rusty pliers, no anesthesia, no disinfectant, and no complaints. And shadowy saloons promising every pleasure under the sun, cafes full of hookah-sucking men, and brothels for all purses and predilections. And the air was permeated by a nauseating mixture of tobacco smoke, Turkish coffee aroma, and camel dung stench.

In other words, a typical middle-eastern town of the day and a huge military security and discipline nightmare. And a new and strange experience for young cadets away from home and the civilities of a sheltered, upper-middle-class upbringing we all had in a clean and well-disciplined, under the oppressive Metaxas dictatorship, prewar city like Athens.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1]Perikles participated in the "The Mutiny in the Middle East." In August 1944, he was tried, discharged, and sentenced to life in

prison. After the Liberation his sentence, like for most of those who participated in the mutiny, was reduced to time served.

[2] Literally: Walnut shell. Metaphorically: a rickety little boat.

[3] Boatswain

[4] Durenda 1922-1956, 7241 tons, British India Steam Navigation Company. In 1956 was sold to Paramount Shipping Corp., Monrovia

renamed ELENE, 1958 scrapped at Odens

[5] Aetos was one of the "Wild Beasts" (in Greek: Θηρία): Αετος ("Eagle"), Ιεραξ ("Hawk"), Πανθηρ ("Panther") and Λεων ("Lion").

[6] Toumbas, "Enemy in Sight,' pp 133-134. Toumbas has nothing but praise for the two cadets (Costas Notaras and Christos)

and the young Dimitris Papasifakis, for their initiative and bravery.

[7] Toumbas' remark may sound crass, but it was not. In the context he said it, it conveyed a rather admiring and affectionate way of welcoming this young boy on board. See page 133 in his book "Enemy in Sight."

[1]Perikles participated in the "The Mutiny in the Middle East." In August 1944, he was tried, discharged, and sentenced to life in

prison. After the Liberation his sentence, like for most of those who participated in the mutiny, was reduced to time served.

[2] Literally: Walnut shell. Metaphorically: a rickety little boat.

[3] Boatswain

[4] Durenda 1922-1956, 7241 tons, British India Steam Navigation Company. In 1956 was sold to Paramount Shipping Corp., Monrovia

renamed ELENE, 1958 scrapped at Odens

[5] Aetos was one of the "Wild Beasts" (in Greek: Θηρία): Αετος ("Eagle"), Ιεραξ ("Hawk"), Πανθηρ ("Panther") and Λεων ("Lion").

[6] Toumbas, "Enemy in Sight,' pp 133-134. Toumbas has nothing but praise for the two cadets (Costas Notaras and Christos)

and the young Dimitris Papasifakis, for their initiative and bravery.

[7] Toumbas' remark may sound crass, but it was not. In the context he said it, it conveyed a rather admiring and affectionate way of welcoming this young boy on board. See page 133 in his book "Enemy in Sight."