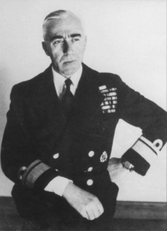

Ioannis Toumbas

Do not follow where the path may lead.

Go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.

Emerson

Vice Admiral Ioannis M. Toumbas

I believe Emerson's wise aphorism would have been an appropriate epitaph for my late skipper because he refused to ... follow where the path was leading. Instead, he went where there was no path and left a 730 mile ( of which 400 were within the range of Luftwaffe's bombers) trail sailing his crippled ship back to her base, in Alexandria, and into naval history.

I first met Admiral Toumbas when he summoned us, the "DURENTA 7," aboard the AETOS, the ship he was commanding at that time. The "DURENTA 7" was a group of seven: Four sailors, Costas Notaras, my brother Mimis, and I—all escapees from the German-occupied Greece on our way to Alexandria, Egypt, to join our fleet.

We had just arrived in Port Said on board the freighter DURENTA—thus the moniker" DURENTA 7"—when the then CDR Toumbas, skipper of AETOS, learned about us and sent his adjutant to meet us with the request/order to follow him to AETOS.

Admiral Toumbas immediately impressed me as an officer and a gentleman. An outstanding officer, courageous and daring with a distinguished naval career who was endowed with all those traits required of a leader, especially of a naval officer during battle. He knew how to command and inspire the men serving under him because, unlike some commanders, Toumbas did not lack the common touch when dealing with his crew. He was demanding but fair. Not the mollycoddling "Popularity Hound" type. He would yell at times, but without "paroxysms of passion." He was easy to approach without that swank which lesser officers seem to think it necessary to adopt.

Of course, every ship captain has his own leadership style which depends on his talents and temperament. Some, like Toumbas, use the power of their personality as well as their considerable skills and physical courage, or a well-timed joke, to inspire their officers and men to do their bidding. The less talented ones rely on berating, cursing, blasphemy and the implicit threat of a bad performance rating.

On ADRIAS were eleven officers, thirty-six non-commissioned officers and one hundred fifty-six sailors. He knew them all by face and name, because he had personally selected (handpicked?) most of them, like me. No doubt he had the ability of getting a clear read on people. And the crew, sailors, NCO's, and Officers respected him as an officer and as a warrior; endowed with good personality traits that made them "work harder" to do their jobs well for the common good. A testament to his men's loyalty was that none of the ADRIAS men were later involved in the "Mutiny in the Middle East " [1,2].

ADRIAS' Officers, NCO's, and ratings were arguably among the best in the world. And although there were many remarkable Greek and British WW II naval officers in the Mediterranean-India theater of war, Admiral Toumbas commanded a special kind of respect and admiration among his contemporaries.

He went on to become the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and retired as Vice Admiral. After his retirement, he became a distinguished member of the Academy of Athens, member of the Parliament, Minister of the Interior and Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Undoubtedly, he was one of the most loved and respected officers in the fleet. It has been an honor and a privilege to have served under him, be mentored by him, and be called friend by him!

Rest in peace Admiral, Friend, Hero!

Cmdre Christos E. Papasifakis

September 2013

Ag. Paraskevi, Greece.

_____________________________________________________

[1] Toumbas, “Enemy in Sight,” pages 455-521:

Note: In the Spring of 1944, a mutiny erupted in the ships and the Naval shore facilities in Egypt. Sailors Revolutionary

Committees seized the ships demanding from the Greek Government-in-exile in Cairo to include EAM (the

National Resistance Front, the “Government of the Mountain,” controlled by communists) in the Government of Greece

after the Liberation. Eventually, the mutiny was crushed by force of arms, with several casualties on both sides. See "TO XASTOUKI" tab

for more information about the mutiny.

[2] Dimitrakopoulos, "WW II The Warriors of the Navy Remember...," pages 153-155:

Note: In the Spring of 1944, Christos was in England as a member of a mission to receive two new destroyers.

Much to his sorrow, and to National embarrassment, due to the events in Alexandria and the Incident at Chatham,

the British refused to transfer two ships to the Greek Navy. Christos gives a detailed account of the Incident, in the

"XASTOUKI" (the slap in the face) tab in this website.

[1] Toumbas, “Enemy in Sight,” pages 455-521:

Note: In the Spring of 1944, a mutiny erupted in the ships and the Naval shore facilities in Egypt. Sailors Revolutionary

Committees seized the ships demanding from the Greek Government-in-exile in Cairo to include EAM (the

National Resistance Front, the “Government of the Mountain,” controlled by communists) in the Government of Greece

after the Liberation. Eventually, the mutiny was crushed by force of arms, with several casualties on both sides. See "TO XASTOUKI" tab

for more information about the mutiny.

[2] Dimitrakopoulos, "WW II The Warriors of the Navy Remember...," pages 153-155:

Note: In the Spring of 1944, Christos was in England as a member of a mission to receive two new destroyers.

Much to his sorrow, and to National embarrassment, due to the events in Alexandria and the Incident at Chatham,

the British refused to transfer two ships to the Greek Navy. Christos gives a detailed account of the Incident, in the

"XASTOUKI" (the slap in the face) tab in this website.