Explosion

Explosion

"We make war so that we may live in peace."

Ariistotle

At 7:15 p.m. on October 22, 1943, all four ships, under cover of darkness, left Yenti Atala. Soon after, Jervis and Pathfinder sailed toward Leros whereas Hurworth and Adrias steamed toward the strait of Kos and from there to Kalymnos. Naturally, we were under "battle orders." Spotters, pointers, and trainers stood beside their loaded guns holding shells, ready for action. Thoughts were racing through my head. I was mentally checking and re-checking everything to make sure my turret was ready for action.

And then the thought that we may sink crossed my mind, perhaps because of last night's experience. Of course, we had much to fear, for we were tempting fate sailing in German-controlled waters where the likelihood of a lethal engagement was high. But when the blood is running hot in a sailor's veins and his heart is racing, it's difficult to tell excitement from fear. However, looking at my men standing ready for action, I immediately perished that thought. My training and that mysterious group enthusiasm known as "esprit de corps" which our ship possessed, combined with my intense feelings of patriotism and deep confidence in our captain, made me feel invincible.

Perhaps some of this hubris came from my mother who taught me, and my brothers, that one's priorities in life ought to be: To his country, to God, and to his family.

Undoubtedly, the same thought about sinking was crossing everyone's mind. But it did not stop anyone from doing their jobs in the best humanly possible way. And I say "humanly possible" because, I remember in one of Sophocles' tragedies the diachronic truth: "As God disposes, man laughs or weeps".

It is interesting to note that men during war, facing danger and possible death, develop a state of mind where tragedy and comedy so often blend together—they are apt to dwell on the humorous than the tragic side of life. I remember before we left Yenti Atale, a sailor in the chow line saying to another sailor "eat, because you will never eat again!" The other one burst out laughing, but he never ate again...!

The ancient Greeks had a proverb: "You can not avoid what is written" (Tο πεπρωμένο φυγείν αδύνατον). Of course, the fact that I am around reminiscing with you [George] is a testament to the wisdom of that aphorism. As another example, I remember being ordered to send one of my turret's crewmen to the fore turret to replace one of theirs who had hurt himself and was sent to the sick bay. As Toumbas had made an arbitrary but fateful decision to assign me to the aft turret and Themelis to the fore, I too made an arbitrary decision when I sent one of my men to the fore turret. He was killed within the hour along with most of Themelis' men in the fore turret.

Ariistotle

At 7:15 p.m. on October 22, 1943, all four ships, under cover of darkness, left Yenti Atala. Soon after, Jervis and Pathfinder sailed toward Leros whereas Hurworth and Adrias steamed toward the strait of Kos and from there to Kalymnos. Naturally, we were under "battle orders." Spotters, pointers, and trainers stood beside their loaded guns holding shells, ready for action. Thoughts were racing through my head. I was mentally checking and re-checking everything to make sure my turret was ready for action.

And then the thought that we may sink crossed my mind, perhaps because of last night's experience. Of course, we had much to fear, for we were tempting fate sailing in German-controlled waters where the likelihood of a lethal engagement was high. But when the blood is running hot in a sailor's veins and his heart is racing, it's difficult to tell excitement from fear. However, looking at my men standing ready for action, I immediately perished that thought. My training and that mysterious group enthusiasm known as "esprit de corps" which our ship possessed, combined with my intense feelings of patriotism and deep confidence in our captain, made me feel invincible.

Perhaps some of this hubris came from my mother who taught me, and my brothers, that one's priorities in life ought to be: To his country, to God, and to his family.

Undoubtedly, the same thought about sinking was crossing everyone's mind. But it did not stop anyone from doing their jobs in the best humanly possible way. And I say "humanly possible" because, I remember in one of Sophocles' tragedies the diachronic truth: "As God disposes, man laughs or weeps".

It is interesting to note that men during war, facing danger and possible death, develop a state of mind where tragedy and comedy so often blend together—they are apt to dwell on the humorous than the tragic side of life. I remember before we left Yenti Atale, a sailor in the chow line saying to another sailor "eat, because you will never eat again!" The other one burst out laughing, but he never ate again...!

The ancient Greeks had a proverb: "You can not avoid what is written" (Tο πεπρωμένο φυγείν αδύνατον). Of course, the fact that I am around reminiscing with you [George] is a testament to the wisdom of that aphorism. As another example, I remember being ordered to send one of my turret's crewmen to the fore turret to replace one of theirs who had hurt himself and was sent to the sick bay. As Toumbas had made an arbitrary but fateful decision to assign me to the aft turret and Themelis to the fore, I too made an arbitrary decision when I sent one of my men to the fore turret. He was killed within the hour along with most of Themelis' men in the fore turret.

Leros, Kalymnos, Kos

Around 9:00 p.m. we went through the strait of Kos. Turkish coastal batteries fired at us with small weapons without any effect. We were approaching Kalymnos and according to the plan we were to commence shelling at 10:00 p.m. whether we met enemy ships or not.

The order came down loud and clear in my earphones to “load and stand by." We loaded the guns and the breeches were shut, breaking the quietness of the night with that characteristic dry metallic sound.

The night was black as Erebus. I was standing next to the loaded guns [1], scouring the pitch black horizon with my binoculars and keeping an eye on my wristwatch waiting for the order to commence firing.

Suddenly, at 9:56 p.m. (approx. 36° 59'N, 27° 06'E) the ship rocked and staggered. There was a blinding flash of light followed by that dreadful whump sound of a huge explosion and the whistling hail of metal that knocked us over and send the ship skyward. Within seconds the dark nighttime sky flashed into daylight as ADRIAS violently shook under my feet. The world went away, as well as, every part of my heart. My first thought was that I had accidentally fired my gun. "Goddamn, the Skipper is going to skin me alive," I thought. But before I had time to process that thought an enormous double tremor shook the ship and everything went up in the air flinging projectiles against us in the darkness. And then, for what felt like an eternity, I felt a tremendous force pushing me, and the ship, down, down, down! It seemed that there was nothing to separate us from the after-world—clearly, we were at God's mercy.

The ship took a considerable downward angle, and I slid forward, against the gun base, while bits of metal and human parts flew in all directions, raining down like hail. When normal senses began to return, I was lying face down on the deck. What the hell had happened? I heard hardly distinguishable distant bellows of rage and cries of agony. And a hot putrid air wave reeking of diesel fuel and burning flesh stormed trough the ship that stung my eyeballs and made my lungs hurt. Then I realized that I was sprawled on the floor, pain pulsing through my left leg, still holding the binoculars on the one hand while the other was buried under some debris that had rained down on us. I looked up in the darkness for signs of life in the turret and not sensing any movement I yelled "men, are you here?" They were! All sprawled on the floor and, thankfully, alive!

I felt like I was in a time warp, one I hoped I would soon come out of and realize that all was just a bad dream! Slowly, I flexed my right hand, it seemed okay. I started feeling around for my helmet that had flown off my head. Instead, my fingers found a boot. I grabbed it and pushed it as hard as I could. I felt resistance, Thank God, that meant it was still attached to a living body! I twitched my left foot and bend my knees. Everything worked, although I could not imagine how this was possible. With my heart pounding nearly out of my chest I got up and finally caught my breath. I put the helmet on, adjusted the strap and with a growing determination, I took a quick visual inventory of the turret and the men, ignoring the aches and pains I felt. The impenetrable darkness of the night was gone. Holy f...ing shit! We were alive and the sea was on fire.

Amazingly, besides a few bruises and tears in my uniform and still tasting blood in my mouth from being slammed to the deck, I did not feel anything broken, although the mine's blast had knocked me violently into the turrets' shield. And with the exception for our uniforms being splattered with blood and a superficial laceration zigzagging across a sailor's forehead and some other minor injuries and bruises, nobody in the turret was seriously hurt, although we were all badly shaken. What a relief!

Although by now I was accustomed to living on familiar terms with Death, I never before had it so close, or so persistent. Subconsciously, fishing in my pocket, I thumbed the small cross I had attached to my "komboloi!"* Later I rationalized that the reason we were not burned or crashed was that our turret being in the stern of the ship was as far from where the mine hit as it could possibly be. Or, in more realistic terms, "it was not our time to go."

In the glow of the burning sea and and death staring us in the face, while the ship under me was foundering in the water, I saw clusters of debris, a broken raft, and oil drums float by and tangled wires stretched taut across the deck hanging on the side of the deck disappearing into the sea. That made me think that the mainmast had snapped off taking everything attached to it over the side. But that was not the case. Those were cables from the forecastle that the explosion had blown toward the back of the ship.

Eventually, the ship stopped moving and took a huge list to starboard. The stern was pointing noticeably up. I tried to call the bridge but no answer. The telephone was dead. A quick look around told me that all power was gone. Except for some flashlights and the glow of the burning sea, darkness was everywhere. Because I had not heard any planes, I thought that we had been torpedoed. What else could explain that terrifying explosion and its devastating results? Of course, hitting a mine never crossed my mind because the previous night we had cleared that sector. Later on, we learned that the Germans had laid mines again in that sector early that morning.

For a while, that felt like eons, ADRIAS lay broken on the surface burning and smoking and with a cross-section of her innards exposed to the sea. I am sure we all thought we were doomed. But then she began moving again, slowly backward in a semi-circular path, while the odor of burning flesh permeated the whole ship. With the ship moving, seemingly animated by our defiant will to survive, our spirits soared. Only then did I clearly hear the groans and moans of the wounded coming from the front of the ship. Without orders coming down the line, I was torn between staying put or rushing toward the sound of the moaning to help. I tried the telephone but it was still dead. A few minutes later, which felt like eternity, I saw the damage control brigade and bloodied disheveled sailors and officers rushing by to put out small electrical fires. I yelled to them hoping the officer in charge would order me to join them, but no answer. I tried again the telephone but it was still dead. I was literally and figuratively in the dark as to what had happened or what my new orders were. Amid the chaos, and without orders, I decided not to leave my post. I figured it would be best to stick to my orders, having the guns ready to defend our ship. I am glad I did, because shortly after the explosion a threat to our ship appeared out of nowhere.[7]

The order came down loud and clear in my earphones to “load and stand by." We loaded the guns and the breeches were shut, breaking the quietness of the night with that characteristic dry metallic sound.

The night was black as Erebus. I was standing next to the loaded guns [1], scouring the pitch black horizon with my binoculars and keeping an eye on my wristwatch waiting for the order to commence firing.

Suddenly, at 9:56 p.m. (approx. 36° 59'N, 27° 06'E) the ship rocked and staggered. There was a blinding flash of light followed by that dreadful whump sound of a huge explosion and the whistling hail of metal that knocked us over and send the ship skyward. Within seconds the dark nighttime sky flashed into daylight as ADRIAS violently shook under my feet. The world went away, as well as, every part of my heart. My first thought was that I had accidentally fired my gun. "Goddamn, the Skipper is going to skin me alive," I thought. But before I had time to process that thought an enormous double tremor shook the ship and everything went up in the air flinging projectiles against us in the darkness. And then, for what felt like an eternity, I felt a tremendous force pushing me, and the ship, down, down, down! It seemed that there was nothing to separate us from the after-world—clearly, we were at God's mercy.

The ship took a considerable downward angle, and I slid forward, against the gun base, while bits of metal and human parts flew in all directions, raining down like hail. When normal senses began to return, I was lying face down on the deck. What the hell had happened? I heard hardly distinguishable distant bellows of rage and cries of agony. And a hot putrid air wave reeking of diesel fuel and burning flesh stormed trough the ship that stung my eyeballs and made my lungs hurt. Then I realized that I was sprawled on the floor, pain pulsing through my left leg, still holding the binoculars on the one hand while the other was buried under some debris that had rained down on us. I looked up in the darkness for signs of life in the turret and not sensing any movement I yelled "men, are you here?" They were! All sprawled on the floor and, thankfully, alive!

I felt like I was in a time warp, one I hoped I would soon come out of and realize that all was just a bad dream! Slowly, I flexed my right hand, it seemed okay. I started feeling around for my helmet that had flown off my head. Instead, my fingers found a boot. I grabbed it and pushed it as hard as I could. I felt resistance, Thank God, that meant it was still attached to a living body! I twitched my left foot and bend my knees. Everything worked, although I could not imagine how this was possible. With my heart pounding nearly out of my chest I got up and finally caught my breath. I put the helmet on, adjusted the strap and with a growing determination, I took a quick visual inventory of the turret and the men, ignoring the aches and pains I felt. The impenetrable darkness of the night was gone. Holy f...ing shit! We were alive and the sea was on fire.

Amazingly, besides a few bruises and tears in my uniform and still tasting blood in my mouth from being slammed to the deck, I did not feel anything broken, although the mine's blast had knocked me violently into the turrets' shield. And with the exception for our uniforms being splattered with blood and a superficial laceration zigzagging across a sailor's forehead and some other minor injuries and bruises, nobody in the turret was seriously hurt, although we were all badly shaken. What a relief!

Although by now I was accustomed to living on familiar terms with Death, I never before had it so close, or so persistent. Subconsciously, fishing in my pocket, I thumbed the small cross I had attached to my "komboloi!"* Later I rationalized that the reason we were not burned or crashed was that our turret being in the stern of the ship was as far from where the mine hit as it could possibly be. Or, in more realistic terms, "it was not our time to go."

In the glow of the burning sea and and death staring us in the face, while the ship under me was foundering in the water, I saw clusters of debris, a broken raft, and oil drums float by and tangled wires stretched taut across the deck hanging on the side of the deck disappearing into the sea. That made me think that the mainmast had snapped off taking everything attached to it over the side. But that was not the case. Those were cables from the forecastle that the explosion had blown toward the back of the ship.

Eventually, the ship stopped moving and took a huge list to starboard. The stern was pointing noticeably up. I tried to call the bridge but no answer. The telephone was dead. A quick look around told me that all power was gone. Except for some flashlights and the glow of the burning sea, darkness was everywhere. Because I had not heard any planes, I thought that we had been torpedoed. What else could explain that terrifying explosion and its devastating results? Of course, hitting a mine never crossed my mind because the previous night we had cleared that sector. Later on, we learned that the Germans had laid mines again in that sector early that morning.

For a while, that felt like eons, ADRIAS lay broken on the surface burning and smoking and with a cross-section of her innards exposed to the sea. I am sure we all thought we were doomed. But then she began moving again, slowly backward in a semi-circular path, while the odor of burning flesh permeated the whole ship. With the ship moving, seemingly animated by our defiant will to survive, our spirits soared. Only then did I clearly hear the groans and moans of the wounded coming from the front of the ship. Without orders coming down the line, I was torn between staying put or rushing toward the sound of the moaning to help. I tried the telephone but it was still dead. A few minutes later, which felt like eternity, I saw the damage control brigade and bloodied disheveled sailors and officers rushing by to put out small electrical fires. I yelled to them hoping the officer in charge would order me to join them, but no answer. I tried again the telephone but it was still dead. I was literally and figuratively in the dark as to what had happened or what my new orders were. Amid the chaos, and without orders, I decided not to leave my post. I figured it would be best to stick to my orders, having the guns ready to defend our ship. I am glad I did, because shortly after the explosion a threat to our ship appeared out of nowhere.[7]

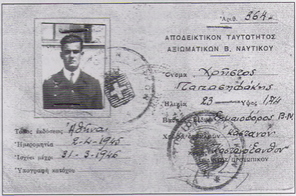

Christos' ID card

As I was going about my business checking the readiness of the turret, the dauntless sub-lieutenant Mourikis rushed up the steel rungs to the turret platform giving me the order to be ready to engage the enemy! "Gun manned and ready, sir," I replied as he was receding in the darkness.

A short distance from our ship a low dark target had been spotted and word had quickly spread through ADRIAS that the "torpedo boat" who had "torpedoed" us was coming back to finish the job!

From my lofty perch on the turret I could hear and see in the glow of a fire at the forecastle the pandemonium that broke out on the deck—men rushing toward the front, some pointing blindly into the darkness and others pointing and trading tales on what they saw. One claiming he saw a sub! Another said he saw a torpedo boat with her men standing on her deck ready to fire ... etc.

Unbeknownst to me, my turret’s guns were the only ones left for the defense of our ship. Nevertheless, I had my orders and I was ready to fire at the target as soon as I could make visual contact. But at that moment, Hurworth pulled close, between us and the target. Waiting for Hurworth to leave so I could get a clear view of the target, I saw her suddenly rush headlong toward the would-be enemy ship.

From our ship we could clearly hear the metallic sound of the closing of the breech lever of all of her guns. But in just few minutes Hurworth gave up the chase. What looked like a "torpedo boat" was in reality ADRIAS' air locked and still floating cut-off bows that the currents had carried some distance away.

Incidentally, it has been said that had I fired at the target, ADRIAS, and to a lesser extend I, would have had the dubious honor of being the first ship in history where her stern had fired at her bow!

With the "imminent" danger gone, Captain D, our flotilla commander and captain of Hurworth, and future 2nd Lord of the Sea, signals our captain to “stop engines” so he could come alongside to rescue us and then deliver the coup de grâce to our ship. Toumbas was adamant. He was not ready to accept loss or defeat. He refused the order to have our ship sunk—perhaps the most daunting decision in his long and illustrious career. He would only accept the transfer of the wounded and permission to sail towards the Turkish coast. Apparently, the two captains agreed and Hurworth began coming close to us.

At 10:10 Hurworth was about 50-100 yards away from us. All eyes were on her when a thunderous orange fireball erupted at her middle, lifting her up in the air and cutting her into two pieces. Immediately, a torrent of water, lethal objects, and human body parts rained on us—arms, legs, guts, scalps, tongues etc. When I kicked to the side a boot that bounced off my helmet, to my horror, I realized that there was a severed foot still in it.

An eerie quietness had fallen over Adrias as we were watching in horror and disbelief Hurworth disappear in the glow of the burning sea; while the deck around our feet was literally filled with all sorts of debris and human parts—a grim harbinger of our ship's human devastation that we were to see at dawn.

We heard a climatic earsplitting hissing that ended with a thunderclap like sound, and then the unearthly silence of eternity, and Hurworth was no more. In less than a few minutes she disappears before our eyes.[2] Now, we could only see a glow of burning oil more than 100 feet high where Hurworth used to be. That confirmed the end of our small flotilla's partner. In the pitch black night all we could now see were oil stains burning on the surface of the sea [3], like a requiem for the repose of the souls of our dead comrades-in-arms.

In the darkness we could only hear voices coming from the sea. We called friends' names and other common English names we could think of—John, Jim, ... Perry— but no answer. Only indistinguishable cries from victims in the water and from those in the devastation around us on Adrias.

With the small fire that had broken out on Adrias extinguished, a rescue effort was mounted. Sub-lieutenant Mourikis came rushing back toward the stern followed by a few of men. From our station, my men and I heard his order (to his men) to launch the lifeboat. With the danger of the "submarine" stalking us over and my earphone dead, that was the excuse I wanted. I took it as my order, as well, and without challenging it or asking for order clarification me and my crew rushed down to the boat deck. Mourikis was kind of surprised but appreciative of the extra hands. He immediately put me in charge of the operation—now, I had my new orders!

We pulled the pins, hoisted the boat off its blocks, and swung her about her davits over the water. We lowered her on a rather calm but oily sea and once entirely water-borne we grabbed the lifelines and lowered ourselves aboard her—myself, two of my men and one of Mourikis'. Then, very slowly, we began rowing; dodging bobbing corpses and being careful to avoid hitting any survivors. We plucked two of our men from the oily sea who had been blown overboard. It was pure luck that we found them among the floating debris, it gave us high hopes of finding others. Carefully we approached the waters where Hurworth had sunk. We circled and crisscrossed the area several times hoping to find more survivors, but no more were to be found. Disappointed and with heavy hearts and eyes burning from the acrid smoke of the burning sea, but still thankful for finding our two sailors, we turned and rowed back.

We tied the boat at ADRIAS' side, and as she was rocking in the water and banging against ADRIAS' hull, we lifted up the survivors to outstretched waiting hands, dripping oil and sea water on us; and then, we climbed up. As Mourikis' men were taking care of the rescued survivors, we hauled up and secured the boat. And without waiting for any further orders we hurried back to our turret, wet and oily, walking up a steep angle to get to it. But, as ADRIAS took her first precarious steps to her survival trip for Turkey, we rushed down, again, to the main deck to help throw overboard life vests, rafts, and planks of wood for possible survivors that we perhaps had not seen or heard during the rescue effort.

As we were retreating toward Turkey, for a few miles we could still see, in waters steadily burning from the oil slicks, ADRIAS' bow remaining afloat, drifting away with the currents. And as darkness began enveloping the ship, the flicker of flashlights and the diminished glow of the distant fires made Death more present and terror (Δεῖμος) [7] more palpable than before—even the shadows thrown on the bulkhead looked like threatening ghosts on the prowl. And every pitch of the ship was feared as her last.

About ten Hayworth sailors, who had the physical strength, or the will to live, managed to swim ashore and land on Pserimos, a German-controlled small island of fishermen, goat-herders, and small farmers. But because of its small population did not have a German garrison on it. Later on, the survivors had nothing but praise for the locals and especially for Basilis Mamouzelos, the local "Mayor" of sorts, under whose leadership the islanders cleaned, fed, sheltered, and helped them escape to Turkey. They arrived in Gumusluk a couple of days after we did and were immediately taken to Ali's Coffeehouse, the de facto "hospital" and "General Staff" Headquarters, for debriefing, feeding and medical attention of the wounded. Then the able-bodied came over for a "tour" of ADRIAS. We knew them all, because our ships had worked as a team before the disaster. A couple of days later the wounded were taken to Smyrna and the other 5-6 were taken to Bodrum.

Adrias had a special fondness for Hurworth, her officers, and her crew. She had been our long time companion in so many missions that her tragic end, under our unfortunate circumstances, made us feel very sad and alone.

A short distance from our ship a low dark target had been spotted and word had quickly spread through ADRIAS that the "torpedo boat" who had "torpedoed" us was coming back to finish the job!

From my lofty perch on the turret I could hear and see in the glow of a fire at the forecastle the pandemonium that broke out on the deck—men rushing toward the front, some pointing blindly into the darkness and others pointing and trading tales on what they saw. One claiming he saw a sub! Another said he saw a torpedo boat with her men standing on her deck ready to fire ... etc.

Unbeknownst to me, my turret’s guns were the only ones left for the defense of our ship. Nevertheless, I had my orders and I was ready to fire at the target as soon as I could make visual contact. But at that moment, Hurworth pulled close, between us and the target. Waiting for Hurworth to leave so I could get a clear view of the target, I saw her suddenly rush headlong toward the would-be enemy ship.

From our ship we could clearly hear the metallic sound of the closing of the breech lever of all of her guns. But in just few minutes Hurworth gave up the chase. What looked like a "torpedo boat" was in reality ADRIAS' air locked and still floating cut-off bows that the currents had carried some distance away.

Incidentally, it has been said that had I fired at the target, ADRIAS, and to a lesser extend I, would have had the dubious honor of being the first ship in history where her stern had fired at her bow!

With the "imminent" danger gone, Captain D, our flotilla commander and captain of Hurworth, and future 2nd Lord of the Sea, signals our captain to “stop engines” so he could come alongside to rescue us and then deliver the coup de grâce to our ship. Toumbas was adamant. He was not ready to accept loss or defeat. He refused the order to have our ship sunk—perhaps the most daunting decision in his long and illustrious career. He would only accept the transfer of the wounded and permission to sail towards the Turkish coast. Apparently, the two captains agreed and Hurworth began coming close to us.

At 10:10 Hurworth was about 50-100 yards away from us. All eyes were on her when a thunderous orange fireball erupted at her middle, lifting her up in the air and cutting her into two pieces. Immediately, a torrent of water, lethal objects, and human body parts rained on us—arms, legs, guts, scalps, tongues etc. When I kicked to the side a boot that bounced off my helmet, to my horror, I realized that there was a severed foot still in it.

An eerie quietness had fallen over Adrias as we were watching in horror and disbelief Hurworth disappear in the glow of the burning sea; while the deck around our feet was literally filled with all sorts of debris and human parts—a grim harbinger of our ship's human devastation that we were to see at dawn.

We heard a climatic earsplitting hissing that ended with a thunderclap like sound, and then the unearthly silence of eternity, and Hurworth was no more. In less than a few minutes she disappears before our eyes.[2] Now, we could only see a glow of burning oil more than 100 feet high where Hurworth used to be. That confirmed the end of our small flotilla's partner. In the pitch black night all we could now see were oil stains burning on the surface of the sea [3], like a requiem for the repose of the souls of our dead comrades-in-arms.

In the darkness we could only hear voices coming from the sea. We called friends' names and other common English names we could think of—John, Jim, ... Perry— but no answer. Only indistinguishable cries from victims in the water and from those in the devastation around us on Adrias.

With the small fire that had broken out on Adrias extinguished, a rescue effort was mounted. Sub-lieutenant Mourikis came rushing back toward the stern followed by a few of men. From our station, my men and I heard his order (to his men) to launch the lifeboat. With the danger of the "submarine" stalking us over and my earphone dead, that was the excuse I wanted. I took it as my order, as well, and without challenging it or asking for order clarification me and my crew rushed down to the boat deck. Mourikis was kind of surprised but appreciative of the extra hands. He immediately put me in charge of the operation—now, I had my new orders!

We pulled the pins, hoisted the boat off its blocks, and swung her about her davits over the water. We lowered her on a rather calm but oily sea and once entirely water-borne we grabbed the lifelines and lowered ourselves aboard her—myself, two of my men and one of Mourikis'. Then, very slowly, we began rowing; dodging bobbing corpses and being careful to avoid hitting any survivors. We plucked two of our men from the oily sea who had been blown overboard. It was pure luck that we found them among the floating debris, it gave us high hopes of finding others. Carefully we approached the waters where Hurworth had sunk. We circled and crisscrossed the area several times hoping to find more survivors, but no more were to be found. Disappointed and with heavy hearts and eyes burning from the acrid smoke of the burning sea, but still thankful for finding our two sailors, we turned and rowed back.

We tied the boat at ADRIAS' side, and as she was rocking in the water and banging against ADRIAS' hull, we lifted up the survivors to outstretched waiting hands, dripping oil and sea water on us; and then, we climbed up. As Mourikis' men were taking care of the rescued survivors, we hauled up and secured the boat. And without waiting for any further orders we hurried back to our turret, wet and oily, walking up a steep angle to get to it. But, as ADRIAS took her first precarious steps to her survival trip for Turkey, we rushed down, again, to the main deck to help throw overboard life vests, rafts, and planks of wood for possible survivors that we perhaps had not seen or heard during the rescue effort.

As we were retreating toward Turkey, for a few miles we could still see, in waters steadily burning from the oil slicks, ADRIAS' bow remaining afloat, drifting away with the currents. And as darkness began enveloping the ship, the flicker of flashlights and the diminished glow of the distant fires made Death more present and terror (Δεῖμος) [7] more palpable than before—even the shadows thrown on the bulkhead looked like threatening ghosts on the prowl. And every pitch of the ship was feared as her last.

About ten Hayworth sailors, who had the physical strength, or the will to live, managed to swim ashore and land on Pserimos, a German-controlled small island of fishermen, goat-herders, and small farmers. But because of its small population did not have a German garrison on it. Later on, the survivors had nothing but praise for the locals and especially for Basilis Mamouzelos, the local "Mayor" of sorts, under whose leadership the islanders cleaned, fed, sheltered, and helped them escape to Turkey. They arrived in Gumusluk a couple of days after we did and were immediately taken to Ali's Coffeehouse, the de facto "hospital" and "General Staff" Headquarters, for debriefing, feeding and medical attention of the wounded. Then the able-bodied came over for a "tour" of ADRIAS. We knew them all, because our ships had worked as a team before the disaster. A couple of days later the wounded were taken to Smyrna and the other 5-6 were taken to Bodrum.

Adrias had a special fondness for Hurworth, her officers, and her crew. She had been our long time companion in so many missions that her tragic end, under our unfortunate circumstances, made us feel very sad and alone.

Hurworth, L28

Meanwhile, ADRIAS' list to starboard had increased considerably.

Besides the bow being cut off, the force of the explosion had thrown the forward four-inch twin-gun turret, with its base, on the top of the bridge with its guns pointing toward the stern. Consequently, everything on the bridge was destroyed. Glass, sheets of metal, bodies, and torn woodwork were strewn everywhere.

Toumbas, although wounded, was determined to beach the ship in the nearby Turkish coast. With the aid of Sub-Lieutenant Mourikis the "bridge" was transferred at the middle searchlight where there was a secondary command post. And slowly but surely captain Toumbas began the first leg of Adrias' epic journey—chronicled in detail in his superb book "Enemy in Sight." [4]

ADRIAS had taken a starboard list and had settled by the head. The crew was undaunted; all able-bodied men who had survived the explosion remained in their posts. Fortunately, the boilers and the engines were working fine. The ship was moving, albeit two steps forward one backward, swerving from her course, and hardly responding to the rudder because the wreckage hanging underneath acted as rudder.

The artillery guidance system was destroyed. So the only means of defending our ship was my turret’s twin four-inch guns,[5] although we all knew that these guns could not adequately defend the ship in case of a sea or aerial attack.

The damage control party, led by the First Engineer, Lieutenant Arapes, and the Second Engineer, Sub-Lieutenant Efthimiou, was valiantly trying to stave off the sea pouring in the officers’ lounge and take care of other most urgent repairs.

Meanwhile, the listing of the ship was increasing; we transferred weights and anything that could be moved, including the crew quarters, at the very end of the stern to counterbalance the forward tilt of the boat. Then the oil reservoirs were emptied trying to fight a hard and relentless struggle with time--under the circumstances, a formidable enemy. We were approaching land but the listing was increasing. Pretty soon the propeller will begin breaking the surface. By now it was impossible to steer the ship, she did not respond to the rudder at all. Captain Toumbas kept her in course with the engines. Meanwhile, in case we were sunk, anything of tactical value—codes, ciphers, secret documents—were stuffed in special weighted sacks and thrown into the sea. My men and I joined special demolition parties to destroy the damaged radar, the anti-submarine equipment, and the cryptography machines. A superhuman effort was made by all to save our ship and new pages of heroism and self-sacrifice were written in the annals of our Navy.

Since we all were relocated toward the stern, it was decided to sail the normal way, bow first—although the bow was missing. That way, if we were unlucky enough to hit another mine, it was hoped that we would save many of the crew and the wounded . All maps and the compass were destroyed. Captain Toumbas kept on course guided by the Polar Star. The course was difficult due to the many islands around us. A small mistake and we could arrive into a German-occupied island where captivity or death was awaiting. We were sailing on a zigzag course and only God’s hand steered us safely through the minefields—it was verified later that there were three.

Although danger and the grotesque were the normal course of life now, morale seemed higher than should have been possible under the circumstances. All able-bodied men, officers, petty officers, and sailors were doing their best to save the ship. As the ship groped her way toward Turkey, from my post, while scanning the darkness for potential threats, I could hear captain Toumbas, with a strain in his voice, calling on the first Engineer, Lt. Arape, imploring him to keep the engines going for a bit more: “Arapeee..., [6] hold on for ten…for five minutes!. Just do what you can for me. Just keep the engine going; just give me two more minutes. That’s all I ask for.”

Undoubtedly, our superbly talented Firsts Engineer, Lt. Arapes, never heard Toumbas' pleadings. Nevertheless, thanks to his engineering genius, Toumbas got the extra few minutes he asked for!

How a ship in that condition could still make headway defied logic. No doubt, it is a testament to her builder's technical know-how, Toumbas' masterful seamanship, and Arapes' engineering acumen. Adrias limped, inch-by-harrowing-inch in the darkness. And shortly after midnight, in the early hours of October 23, 1943, although the ship was in danger of capsizing, was finally beached, as if she were a landing craft, in the sandy cove of Gümüşlük, the ancient city of Myndos. It was a matter of minutes and she would have capsized.

Besides the bow being cut off, the force of the explosion had thrown the forward four-inch twin-gun turret, with its base, on the top of the bridge with its guns pointing toward the stern. Consequently, everything on the bridge was destroyed. Glass, sheets of metal, bodies, and torn woodwork were strewn everywhere.

Toumbas, although wounded, was determined to beach the ship in the nearby Turkish coast. With the aid of Sub-Lieutenant Mourikis the "bridge" was transferred at the middle searchlight where there was a secondary command post. And slowly but surely captain Toumbas began the first leg of Adrias' epic journey—chronicled in detail in his superb book "Enemy in Sight." [4]

ADRIAS had taken a starboard list and had settled by the head. The crew was undaunted; all able-bodied men who had survived the explosion remained in their posts. Fortunately, the boilers and the engines were working fine. The ship was moving, albeit two steps forward one backward, swerving from her course, and hardly responding to the rudder because the wreckage hanging underneath acted as rudder.

The artillery guidance system was destroyed. So the only means of defending our ship was my turret’s twin four-inch guns,[5] although we all knew that these guns could not adequately defend the ship in case of a sea or aerial attack.

The damage control party, led by the First Engineer, Lieutenant Arapes, and the Second Engineer, Sub-Lieutenant Efthimiou, was valiantly trying to stave off the sea pouring in the officers’ lounge and take care of other most urgent repairs.

Meanwhile, the listing of the ship was increasing; we transferred weights and anything that could be moved, including the crew quarters, at the very end of the stern to counterbalance the forward tilt of the boat. Then the oil reservoirs were emptied trying to fight a hard and relentless struggle with time--under the circumstances, a formidable enemy. We were approaching land but the listing was increasing. Pretty soon the propeller will begin breaking the surface. By now it was impossible to steer the ship, she did not respond to the rudder at all. Captain Toumbas kept her in course with the engines. Meanwhile, in case we were sunk, anything of tactical value—codes, ciphers, secret documents—were stuffed in special weighted sacks and thrown into the sea. My men and I joined special demolition parties to destroy the damaged radar, the anti-submarine equipment, and the cryptography machines. A superhuman effort was made by all to save our ship and new pages of heroism and self-sacrifice were written in the annals of our Navy.

Since we all were relocated toward the stern, it was decided to sail the normal way, bow first—although the bow was missing. That way, if we were unlucky enough to hit another mine, it was hoped that we would save many of the crew and the wounded . All maps and the compass were destroyed. Captain Toumbas kept on course guided by the Polar Star. The course was difficult due to the many islands around us. A small mistake and we could arrive into a German-occupied island where captivity or death was awaiting. We were sailing on a zigzag course and only God’s hand steered us safely through the minefields—it was verified later that there were three.

Although danger and the grotesque were the normal course of life now, morale seemed higher than should have been possible under the circumstances. All able-bodied men, officers, petty officers, and sailors were doing their best to save the ship. As the ship groped her way toward Turkey, from my post, while scanning the darkness for potential threats, I could hear captain Toumbas, with a strain in his voice, calling on the first Engineer, Lt. Arape, imploring him to keep the engines going for a bit more: “Arapeee..., [6] hold on for ten…for five minutes!. Just do what you can for me. Just keep the engine going; just give me two more minutes. That’s all I ask for.”

Undoubtedly, our superbly talented Firsts Engineer, Lt. Arapes, never heard Toumbas' pleadings. Nevertheless, thanks to his engineering genius, Toumbas got the extra few minutes he asked for!

How a ship in that condition could still make headway defied logic. No doubt, it is a testament to her builder's technical know-how, Toumbas' masterful seamanship, and Arapes' engineering acumen. Adrias limped, inch-by-harrowing-inch in the darkness. And shortly after midnight, in the early hours of October 23, 1943, although the ship was in danger of capsizing, was finally beached, as if she were a landing craft, in the sandy cove of Gümüşlük, the ancient city of Myndos. It was a matter of minutes and she would have capsized.

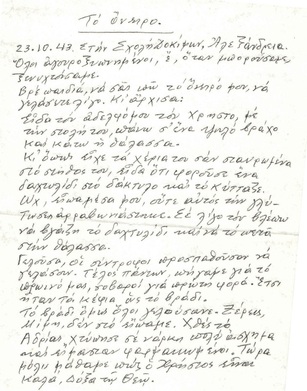

A page from Mimis' diary

A page from Mimis' diary

-------------------- THE DREAM -------------------------

(from Mimis' Diary)

23.10.43 (10/23/1943) Cadet in the Naval Academy in Alexandria.

We got up in the morning as usual, tired from last night's partying, and as we were walking toward the mess hall for breakfast I told my buddies "let me tell you about my dream so you can laugh!" And I began:

I dreamed that my brother, Christos, was standing on the top of a cliff above the sea, in full uniform. He had his hands crossed on his chest looking at an engagement ring in his finger.

Oh, no, I thought, not even he could escape from getting engaged! But then I saw him take the ring off of his finger and throw it in the sea!

I laughed, expecting the others to laugh and make the usual irreverent comments! But I was rather surprised that my friends did not burst into laughter. They just smiled in a rather patronizing way without the usual banter. The rest of the day they were unusually quiet but I did not make anything of it.

Late in the evening they burst into my room, laughing and joking. Then the leader of the group, in a serious voice, said: "You know Mimis, we did not know how to break the news to you. Last night ADRIAS hit a mine with devastating results. We were expecting the worst. However, we just learned that Christos is OK."

Thank you God!

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

(from Mimis' Diary)

23.10.43 (10/23/1943) Cadet in the Naval Academy in Alexandria.

We got up in the morning as usual, tired from last night's partying, and as we were walking toward the mess hall for breakfast I told my buddies "let me tell you about my dream so you can laugh!" And I began:

I dreamed that my brother, Christos, was standing on the top of a cliff above the sea, in full uniform. He had his hands crossed on his chest looking at an engagement ring in his finger.

Oh, no, I thought, not even he could escape from getting engaged! But then I saw him take the ring off of his finger and throw it in the sea!

I laughed, expecting the others to laugh and make the usual irreverent comments! But I was rather surprised that my friends did not burst into laughter. They just smiled in a rather patronizing way without the usual banter. The rest of the day they were unusually quiet but I did not make anything of it.

Late in the evening they burst into my room, laughing and joking. Then the leader of the group, in a serious voice, said: "You know Mimis, we did not know how to break the news to you. Last night ADRIAS hit a mine with devastating results. We were expecting the worst. However, we just learned that Christos is OK."

Thank you God!

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

___________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Toumbas, in his book "Enemy in Sight," page 340-341, writes:

On September 17, Adrias and Hursley arrived in Alexandria to escort with two other destroyers a very important convoy to

Taranto, Italy's Southern Naval Base....

It was then that two new officers came on board. Ensigns Christos Papasifakis and K. Themelis, both recent graduated from the Naval

Academy in Alexandria. Both were from the first who had escaped from Greece. Papasifakis was the one whom I had met on Aetos when

he arrived in Pot Said. Themelis was my nephew. Both these young lads were willing and eager to serve, with high morale and love

for the navy. And in no time at all they proved themselves to be very competent and capable officers.

[2] HURWORTH, on the night of October 22nd, blew up and sank in a matter of minutes. Losses were heavy, but 85 were saved over the

next few days. Her skipper, Cmdr. Wright, was blown off the bridge into the water, with a fractured back, but was rescued by crewman

Savakis from ADRIAS who was also blown of his ship when Adrias hit the mine.

[3] Years later, Admiral Toumbas, on behalf of a thankful nation, was instrumental for the erection of a monument in tribute of the men of HMS HURWORTH. The inscription on the memorial reads:

"Remember that on October 22nd 1945, 134 British Officers and Men of HMS Hurworth

commanded by Commander R. Wright DSO RN nobly risked and lost their ship and lives

to save the company of HHMS Adrias which was in peril."

[4] "Enemy in Sight" an excellent book. A "must read" for every Greek under the age of 80 who would like to learn the glorious role the Greek navy played during WW II.

[5] Toumbas on page 372 in his book "Enemy in Sight" praises Christos. He wrote: "Papasifakis, that young Ensign of only two months, performs his duties with astonishing calm."

[6] Arapes, The 1st Engineer's last name.

[*] "komboloi" : A rosary like string of colorful beads manipulated with one or two hands and used to pass time. A remnant of the Ottoman Empire culture that after the 1960's was fast relegated to the tourist shops.

[7] Deimos and Fovos (Δειμος και Φοβος), (Terror and Fear) are the twin sons of Ares, the God of War in Greek mythology. They always accompanied their father to the war! They are also the moons of Mars.

[1] Toumbas, in his book "Enemy in Sight," page 340-341, writes:

On September 17, Adrias and Hursley arrived in Alexandria to escort with two other destroyers a very important convoy to

Taranto, Italy's Southern Naval Base....

It was then that two new officers came on board. Ensigns Christos Papasifakis and K. Themelis, both recent graduated from the Naval

Academy in Alexandria. Both were from the first who had escaped from Greece. Papasifakis was the one whom I had met on Aetos when

he arrived in Pot Said. Themelis was my nephew. Both these young lads were willing and eager to serve, with high morale and love

for the navy. And in no time at all they proved themselves to be very competent and capable officers.

[2] HURWORTH, on the night of October 22nd, blew up and sank in a matter of minutes. Losses were heavy, but 85 were saved over the

next few days. Her skipper, Cmdr. Wright, was blown off the bridge into the water, with a fractured back, but was rescued by crewman

Savakis from ADRIAS who was also blown of his ship when Adrias hit the mine.

[3] Years later, Admiral Toumbas, on behalf of a thankful nation, was instrumental for the erection of a monument in tribute of the men of HMS HURWORTH. The inscription on the memorial reads:

"Remember that on October 22nd 1945, 134 British Officers and Men of HMS Hurworth

commanded by Commander R. Wright DSO RN nobly risked and lost their ship and lives

to save the company of HHMS Adrias which was in peril."

[4] "Enemy in Sight" an excellent book. A "must read" for every Greek under the age of 80 who would like to learn the glorious role the Greek navy played during WW II.

[5] Toumbas on page 372 in his book "Enemy in Sight" praises Christos. He wrote: "Papasifakis, that young Ensign of only two months, performs his duties with astonishing calm."

[6] Arapes, The 1st Engineer's last name.

[*] "komboloi" : A rosary like string of colorful beads manipulated with one or two hands and used to pass time. A remnant of the Ottoman Empire culture that after the 1960's was fast relegated to the tourist shops.

[7] Deimos and Fovos (Δειμος και Φοβος), (Terror and Fear) are the twin sons of Ares, the God of War in Greek mythology. They always accompanied their father to the war! They are also the moons of Mars.