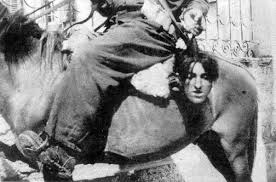

"On the way to collect the price on someone's head" A shocking picture illustrating the extreme barbarity and the magnitude of inhumanity during the fratricidal 1946-49 Greek Civil War.

"On the way to collect the price on someone's head" A shocking picture illustrating the extreme barbarity and the magnitude of inhumanity during the fratricidal 1946-49 Greek Civil War.

"Vae Victis" [1]

"Ουαί τοις ηττημένοις"

"Woe to the vanquished," a diachronic truth since Brennus first uttered it in 390 BC.

Although the Greek Civil War ended in 1949, the gap between "victors" and "vanquished" was unfathomable. Its corrosive legacy—Makronisos, Police Surveillance, Security Dossiers, Certificates of National Allegiance (πιστοποιητικό κοινωνικών φρονημάτων), etc.—lasted until the mid-1980s. Makronisos, Greece's Devil's Island, was the most horrific of all the other internment prison camps--the universities of the Aegean [2]--where communists, suspected communists, former Andartes*, unsophisticated country-folk dreaming of a utopian communist paradise of milk and honey, and those thought to be politically or ideologically a threat to the Government, even vaguely, were thrown in to be "deprogrammed" with various forms of brutality; degradation, humiliation and physical assault on the detainees. Stalin and Churchill, divvying up the spoils of war, drew a line on the map of Europe -- The Percentage Agreement -- thus creating the New World Order with Greece firmly embedded in the Western Alliance. Therefore, any opposition to it had to be crushed.

From the dawn of civilization, Greece has gone through many upheavals, trials and tribulations. The Civil War was but one of them, albeit costly in lives, national treasure, and social integrity, not to mention the devastation of the countryside and the horrific atrocities of vengeance and retribution perpetrated by those on both side of the conflict, although these pale in comparison with the inhumanity at Auschwitz or Hiroshima. But as a Greek Army barrack-ballad says: “Greece Never Dies." ( “Η Ελλαδα Ποτε Δεν Πεθαινει” ).

Greece’s WWII postbellum period is arguably a murky one. Although as I was growing up I had heard a few disconnected stories, because the history we were taught in high school stopped at the 1821 heroes of the War of Independence from the Ottoman Empire. I did not get interested in the subject until the summer of 2013 when I visited my cousin Christos and heard his ADRIAS stories, which are interlinked with the political circumstances that eventually brought about the Greek Civil War tragedy, or as some historians have dubbed it: The first "hot" war of the "Cold War," and where Napalm bombs were used for the first time.

So, I began reading books (see bibliography below) written by both Greek and non-Greek authors to get a balanced picture of the events; events detailing stories of horrific atrocities, incredible acts of bravery and betrayal, love of country and unprecedented savagery, persecution and compassion, and finally redemption.

I include two personal stories below, the "Uncle John" and The "Symmoritis," which brought relevance to me as to the agony Greece was going through in order to maintain her free postwar existence. They give, I believe, a perspective of the prevailing conditions after the Civil War, and although there is no excuse for torture, those were treacherous times, the "Red Tide" was rising threatening to swallow the country. The nation was at risk, the Government had to act. And from what I have read, although her actions were lamentable, not merely severe but barbaric, they were no different than the actions of any other "civilized" nation when faced with danger; brutal internment camps, abusive interrogation methods, sleep deprivation, beatings, death and humiliations.

The “Uncle John”

My father was a cradle-to-grave Royalist born around the turn of the 20th century in the small town of Kranidi, Argolida, Greece, into a rather prosperous family. His grandfather owned and operated a small fleet of boats in the lucrative sponge-diving business of the day, where all of his four sons—my grandfather and his three brothers— worked in the business in various capacities. However, shortly after the family patriarch passed away, as often happens in families with many heirs, the business was torn apart and the brothers were rent asunder by dissension. Thus, to put distance between his brothers, my grandfather moved his family to Piraeus, the port of Athens, where my father grew up having little, if any, further contact with Kranidi or his relatives.

Consequently, I was rather surprised when suddenly one day in the late ‘50s, out of the blue, this “Uncle John” (Μπαρμπα Γιαννης), a cousin of my father’s from Kranidi, came visiting! He was one of those simple country-folk all bone and sinew, a small man with a spark of fervor in his eyes. He was a pleasant man who used to eke out a living for his family by going around the surrounding villages of Kranidi with his donkey peddling ribbons, yarns and sewing notions—a traveling salesman of the day. He had come to Athens to replenish his inventory with the latest threads, pins and needles!

One summer evening in 1968 while visiting Greece, and only after considerable nagging, I finally got my father talking about the war years, of which I knew so little, but had heard so many tall and conflicting stories during my university years from Greek old-timers trying to impress us, college boys.

Here is a sampling of those gems rivaling Munchhausen’s stories, told during meetings of our little “Coffee Society” (παρεα). With the exception of Mr. Lykos, whose name is part of the story, I don’t use real names out of respect for the memory of the protagonists:

- Apostolis: He was boasting that as an OSS [3] operative he was parachuted behind enemy lines in Greece. He was captured by two Germans. One kicked him in the ribs and knocked him to his knees while the other jabbed him in the kidney with his gun and told him, "Mach schnell!" As they were marching him to be interrogated, he dropped to the ground, grabbed a stone, reared back and with perfect aim acquired from months of intense OSS survival training, threw the stone at them. As luck would have it, the stone exploded at the temple of one of his captors, ricocheted and hit the other at the forehead (“στο Δοξα Πατρι”), killing them both, instantly!

PS: I guess the Wehrmacht soldiers were like the Keystone Cops that did not how to handle a prisoner!!! Nevertheless, the group broke into a standing ovation for the "hero" in our midst and into a ton of puzzlement while trying to conceal our dismissive comments under our breath.

- Kostas: He claimed that during a fierce battle at Grammos,[4] while surrounded by Symmorites, his squad ran out of ammunition. He crossed himself three times while loudly reciting the Lord’s Prayer (Πατερ Ημων), and then, after yelling "Guys, let's get the bastards“ ("AERAAA [5] παιδια kαι τους φαγαμε τους πουστηδες )" [6], he and his buddies jumped out of the foxholes and charged toward the rebels (Symmorites). They killed them all with their bare hands, grabbing them two at a time by the hair and smashing their heads together!

PS: For a moment everyone in the group gazed with astonishment, and then broke into a roaring laughter when John Barus, the coffeehouse owner who overheard the story, chimed from behind the counter: "Well, Kosta, were the Symmorites throwing chickpeas at you instead of bullets? “ (Καλα ρε Κωστα, αυτοι στραγαλια σας πεταγανε αντι για σφαιρες? “)

- Rakis: He was another OSS parachutist, who like Apostolis was dropped behind the enemy lines in Gree ce. He was bragging that because he had caused so much damage and mayhem to the Wehrmacht, Hitler had put a price on his head. Hitler, according to him, had issued strict orders, if he were to be captured not be executed. He was to be brought to Berlin so Hitler, himself, could execute him!!!

PS: Apparently Hitler did not have anything else to worry about but obsessing about Rakis. Incidentally,

a more embellished version of this story was printed in Rakis' obituary!

- Mr. Lykos: He was an elderly gentleman, an undersized Santa Clause with his white beard, and an adjunct member of our “Coffee Society,”[8] and we enjoyed his company, too. He was from the environs of Thebes, Greece, claiming that the Symmorites (guerillas) had pillaged his village, stolen his folk's goats and burned his family's house.

His last name, "Lykos," means “wolf” in Greek. So, when sometime later, Tassos, a young engineer

new in town and hailing from Thebes, joined our group, Mr. Lykos eagerly asked him "Are there any

' wolves' [ meaning any of his relatives] left in Thebes?"(Υπαρχουν ακομα Λυκοι στη Θηβα?)

Tassos, unaware of Mr. Lykos' last name answered, "No, the gendarmes killed them all

with poison!" (oχι, οι χωροφυλακες τους σκοτωσαν oλους με φωλα"). The old man was taken aback.

He was horrified! His rosy cheeks turned white, and with sadness in his voice lamented, "The scumbags,

they killed all my relatives!" ("Τα καθικια, μου σκοτωσαν τους συγγενοις." )

PS: With the "Lykos" semantics clarified, Mr. Lykos wholeheartedly joined in the laughter and the

levity that ensued at his expense. Sadly though, at a later "meeting" when the conversation came

around to Alexander the Great, someone interjected that historical evidence were pointing to

Alexander being gay. Mr. Lykos took umbrage to that and stormed out of the coffeehouse—and we

never saw him again! Rest in peace Mr. Lykos!

I guess my father realized that I was not the little boy anymore that he had to protect from the ugly realities of the war and its aftermath; he opened up and told me several stories. The one which brought relevance to me, however, was the one about Uncle John (“Μπαρμπα Γιαννης.”)

Evidently, uncle John, like so many other village and small-town people, was a “coffee-house Communist” who I doubt even knew how to spell the word “communism,” much less that he had ever read or heard about Marx’s or Engel’s theories, nor that had he ever held a gun in his hands. Moreover, I doubt if he could find Moscow on the map!

Apparently, he had been parroting the "coffee-house" communist propaganda around the villages during his “business” rounds. He was arrested and thrown in prison on the island of Hydra (Υδρα).

As soon as the Civil war was over, the Government realized that the majority of the detainees were like "Uncle John;" simple-minded country-folk—communist only in their dreams. Dreaming about social equality and the easy life for all -- between ταβλι, ουζο, and “δεν βαριεσε” (backgammon, ouzo, and “forget about it”)[12]. Evidently, it became clear to the Government that most of the prisoners did not present a clear and present danger to the security of the country. So, they offered amnesty if the prisoner were to declare "μετανοια” (repentance), a declaration that he would denounce the communist “disease”[13] afflicting him or her.

The “uncle,” like most of the other detainees, was not immediately impressed with the idea. Nobody wanted to be known as a "Denouncer" (Δηλωσιας) in their small hometown communities. So, the government tried various ways to sweeten the deal. In uncle John’s case, the National Security apparatus thought of my father, a Royalist, that he might, and should, go to Hydra to persuade his cousin to comply.

My father, prudently, obliged them. The necessary arrangements were made, and he went to Hydra to have a “private” discussion with the uncle. All was good. The uncle was persuaded. The only thing remaining was the next day's formalities before the "prodigal son " free of the communism miasma could return home as a certified real patriot.

The following day, the uncle, brimming with pride having his “Captain” cousin come to his rescue, was ready and eager to denounce any and all things that had to do with the “Left” (την Αριστερα.) He was led in by two gendarmes (χωροφυλακες) into the warden’s office where my father was waiting, having coffee with the warden and making small talk with "Torquemada," a colonel of the National Royal Gendarmerie in charge of the “pardons” proceedings, who was seated behind a huge flat desk in the middle of the room.

Apparently, my father had done a good job because his cousin answered all of the colonel’s questions more than satisfactorily—questions akin to the "Spanish Inquisition" ones: "Do you renounce Communism ? " I do," (“Αποταξασω τον Σατανα? Αποταξαμειν”), etc..

Smiles and "attaboys" were floating all around. The warden was happy, the colonel elated, my father content, and the gendarmes all trying to conceal approving smiles under their authoritative Gendarme mustaches. Freedom was at hand, nothing else to be said or done!

Alas, this chummy muster of sweetness, fellowship, and good manners came to an abrupt end when the colonel shoved a form in front of the uncle and ordered him to sign it. The uncle, although verbally had freely denounced everything that had to do with "the Left," froze when he saw “the form.” Apparently, like many of them, he thought of the social repercussions of being on record as the "village Denouncer," (Δηλωσιας), a stigma exponentially worse than being thought of as the "village idiot," and he refused to sign!

And if that was not enough of a bombshell, to make the awkward situation even worse, he turned to my father and said, “Cousin I don’t care if I denounce them orally, but I don’t want to sign, unless I receive a “dispatch” from Moscow! " (“Ξαδερφε δεν με νοιαζει να τα πω, αλλα δεν υπογραφω αν δεν λαβω “σημα” απο την Μoσχα!")

WHAAAT??? A dispatch?? From wheeere???

My father was thunderstruck, the warden dumbfounded, the colonel furious, and the gendarmes went wild. They grabbed him from the collar of his jacket, lifted him up from the chair in which he was sitting, swung him around, and pushing and shoving got him out of the office, pix-lax (πύξ, λάξ) [17], cussing and spewing a torrent of expletives at him.

My father, apologizing profusely to the warden and the colonel, left as fast and as inconspicuously as he could, getting into the first boat he could find for Piraeus, thankful that they did not arrest him on some drummed up charges, like associating with known communists who receive “dispatches” from Moscow, no less!

Undoubtedly, after that stunt he pulled, the uncle was treated to the notorious “Gendarmerie Hospitality”[14], "ξυλοκοπημα" (a beating), a common Gendarmerie practice at the time. But that rather "unwise" and undoubtedly painful stunt earned him the face-saving excuse he needed to get out without the social stigma of being a Denouncer/Police informant since he was "forced" to sign; and most likely had the bruises to prove it! Nevertheless, the uncle not only survived, but his business thrived, as well!

Incidentally, this story-telling with my father took place after we had returned from visiting that uncle in Kranidi (see picture below). Naturally, the uncle was an old man by now and his donkey had died long time ago. However, he was still peddling pins and needles, but from a small ultra-modern fabric store he owned in which two huge pictures of King Paul and Queen Frederica were prominently displayed on the wall above the cash register.

I am sure there were many like “Uncle John” ensnared in the White Terror’s wide cast net. And although

the country was in peril, in my opinion, there is no excuse for torture and brutality of prisoners and detainees. But with McCarthyism sweeping through America and to keep the Marshall Plan pouring millions of dollars to resuscitate the country after the devastation of the WWII war and the fratricide of the Civil War, in the eyes of the powers that be, the "Policy of Containment " justified anything and everything.

The grim alternative, of course, would have been Greece becoming another Eastern Block satellite, struggling for food and freedom under totalitarian slavery until the fall of the Soviet Union. However, in my opinion, and with the benefit of seventy years of hindsight since the civil war, reprisals not only should have been prohibited but severely punished. The victors should have reached out to the vanquished across the chasm of the national schism to expedite reconciliation and national unity for a faster emergence of a new and dynamic post-war Greece.

The “Symmoritis”

In 1988 cousin Mimis (the Rear Admiral) came visiting me in California. He told me the following poignant story related to his position as the president of the Commission for the Repatriation of the Victims of the Civil War. It's a story about those who willingly or unwillingly had sought refuge in the communist countries at the end of the Civil War and now wanted to return to their towns and villages in Greece.

The Commission's ultimate task was to judge each applicant’s fitness for repatriation depending mainly on whether he/she had committed war crimes, as have been broadly defined by the Nuremberg principles, and not for fighting during the Civil War.

Mimis had arrived at the conclusion that most of those who paraded in front of him were men and women like “Uncle John,” provincial or small-town people swept up by the deceitful promise of equality and the equal distribution of wealth under communism. He described them as a bunch of old men and women, beaten down by life in those inhospitable countries they ran to, or taken to, and an antithesis to those ferocious-looking Andartes and bearded Symmorites he remembered seeing in the newspapers. To him, they looked more like the beaten and demoralized ragtag prisoners he had seen in 1951, when as a young naval lieutenant had led a landing party in the port of Volos to prevent bloodshed between the Gendarmes and their detainees after a food riot had erupted at the pier.

Mimis began: For some reason, I was in uniform that particular day interviewing this old man. It was apparent that he was intimidated by the proceedings and very reserved with his answers. I tried to allay his fears by asking him questions about general and well-known events of the Civil war because from his answers to the other Board members and the security reports I had seen it was evident that he had committed no war crimes.

When I gave him my hand to congratulate and “Welcome” him back to Greece, he held it and with tears in his eyes told me, "May God keep you in good health, Mr. Policeman." ("Ο Θεος να σ’εχη καλα, κυριε Αστυνομε!“)

I smiled and I told him, “I am not a policeman, I am a sailor,” [16] whereupon, he dropped to his knees and kissed my hand. I was stunned. I tried to pull him up but he stayed down holding my hand and with tears in his eyes said, "My brave young man, why didn’t you tell me and I was afraid of you?" ("Παλληκαρι μου γιατι δεν μου τ’ολεγες και σε φοβομουνα? ") And he continued, "I saw the stripes on your sleeves and I thought you were a National Security Officer." (" Ιδα τα σιριτια στα μανικια και σε περασα για Σεκουριστα." )

As I was pulling him up, with a crackle in his voice and tears in his eyes, said, "I was young and hungry. They had promised us Equality under a new Greece. I believed them. I fought and killed compatriots. Please forgive me. I want to die in my village!" ("Ημουν νεος και πειναγα, μας υποσχονταν ισοτητα σε μια Νεα Ελλαδα, πολεμισα και σκοτωσα συμπατριωτες, συγχωραμε, θελω να πεθανω στο χωριο μου!" ).

Τhe will of a magnanimous nation forgave him and welcomed him back to Greece.

God only knows what terrors these people had faced dealing with security officers in those foreign countries behind the Iron Curtain where they sought refuge that the sight of stripes on my uniform's sleeves would strike terror in his heart.

Mimis

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++