Touched by History

Christos, Sub Lt.

Upon arrival in Alexandria, Costas Notaras, Mimis, and I were sent to the cruiser AVEROF which was laid up in the port and on which the Greek Naval Academy (Scholi Dokimon) had been re-instituted. Thus, the four of us, that is Costas, Pericles [who had arrived in Alexandria after his disappearance in Kousadasi] Mimis, and I were again reunited.

My two classmates and I were 2nd-year cadets when we left Athens. From the beginning of June to the end of July we were the only 2nd-year Naval Academy cadets on AVEROF, even when she sailed for Bombay. Others who had escaped from Greece to Alexandria were sent to Bombay and joined our class there.

Because there was a dearth of qualified young men an exception was made for Mimis, he was allowed to take the Academy entrance exam although he was only sixteen-years-old. He passed it, thus becoming the Naval Academy's-in-exile first student and the only first-year cadet until he got to Bombay. Once there, four other young men joined his class. Thus his class becoming the first class of the Greek Naval Academy-in-exile.

One of the first things we did when we arrived in Alexandria was to mail a card to our parents through the Red Cross, to let them know about our safe arrival. There was no way we could have communicated with them during our escape travails. Of course, it took the card more than a couple of months to arrive. But it did! And as Nikos remembers, once our father got it in December, he dropped everything he was doing and excitedly ran home to tell the good news to our mother.

My two classmates and I were 2nd-year cadets when we left Athens. From the beginning of June to the end of July we were the only 2nd-year Naval Academy cadets on AVEROF, even when she sailed for Bombay. Others who had escaped from Greece to Alexandria were sent to Bombay and joined our class there.

Because there was a dearth of qualified young men an exception was made for Mimis, he was allowed to take the Academy entrance exam although he was only sixteen-years-old. He passed it, thus becoming the Naval Academy's-in-exile first student and the only first-year cadet until he got to Bombay. Once there, four other young men joined his class. Thus his class becoming the first class of the Greek Naval Academy-in-exile.

One of the first things we did when we arrived in Alexandria was to mail a card to our parents through the Red Cross, to let them know about our safe arrival. There was no way we could have communicated with them during our escape travails. Of course, it took the card more than a couple of months to arrive. But it did! And as Nikos remembers, once our father got it in December, he dropped everything he was doing and excitedly ran home to tell the good news to our mother.

AVEROF

AVEROF

AVEROF's skipper, where The Academy-in-Exile was operating, was Captain K. Kontogiannis and his executive officer was Lt. Commander A. Spanidis. The Academy was operating with the same standards as the academy in Piraeus. That is lectures, exams, training exercises, punishments, liberties, and naturally the "necessary" hazings of the freshman class.

In addition to being students, all cadets worked as sailors aboard AVEROF [1]. We participated in all on board activities like watch standing, whether in anchorage or at sea, tactical action duty, etc.—while trying to survive on a 3.5 British Pounds per month cadet's salary. Consequently, money was a source of constant worry, hurt, and envy. Over time, we adopted some forms of frugality. For example, sharpening and using razor blades over and over again, etc. Without a doubt, our perks and salaries could hardly be compared with those of our British counterparts, they made a lot more money than we did!

Between May and June of 1941, before leaving for Bombay, the port of Alexandria was daily bombed by the German air force in an effort to establish a reign of terror, especially on nights when the moon was shining. [The island of] Crete had already been captured and Rommel was advancing from the west. Alexandria was at risk. AVEROF with her heavy anti-aircraft weaponry had been assigned her own sector of defense. Notaras, Soutsos and I were assigned to a Vickers [2], where I was the direction-operator and the gun-aimer. My brother Mimis' post was at the searchlight at the stern.

Every night after the moon rose, the air-raid sirens would go off, which meant we had to run to our battle stations. Eventually, due to the changing time of the moon rise, the sirens would go off after we had gone to bed. When the GQ (General Quarters) alarm began ringing all hell would break loose, and the sleeping ship would come alive. There was no question in anyone's mind where to go or what to do. "Rudely awaken," we would jump out of our bunks and run to our posts, barefooted and in our skivvies, sprinting through narrow passageways, only slowing to duck through hatches, racing up ladders and shivering for hours in the cold humid night.

In addition to being students, all cadets worked as sailors aboard AVEROF [1]. We participated in all on board activities like watch standing, whether in anchorage or at sea, tactical action duty, etc.—while trying to survive on a 3.5 British Pounds per month cadet's salary. Consequently, money was a source of constant worry, hurt, and envy. Over time, we adopted some forms of frugality. For example, sharpening and using razor blades over and over again, etc. Without a doubt, our perks and salaries could hardly be compared with those of our British counterparts, they made a lot more money than we did!

Between May and June of 1941, before leaving for Bombay, the port of Alexandria was daily bombed by the German air force in an effort to establish a reign of terror, especially on nights when the moon was shining. [The island of] Crete had already been captured and Rommel was advancing from the west. Alexandria was at risk. AVEROF with her heavy anti-aircraft weaponry had been assigned her own sector of defense. Notaras, Soutsos and I were assigned to a Vickers [2], where I was the direction-operator and the gun-aimer. My brother Mimis' post was at the searchlight at the stern.

Every night after the moon rose, the air-raid sirens would go off, which meant we had to run to our battle stations. Eventually, due to the changing time of the moon rise, the sirens would go off after we had gone to bed. When the GQ (General Quarters) alarm began ringing all hell would break loose, and the sleeping ship would come alive. There was no question in anyone's mind where to go or what to do. "Rudely awaken," we would jump out of our bunks and run to our posts, barefooted and in our skivvies, sprinting through narrow passageways, only slowing to duck through hatches, racing up ladders and shivering for hours in the cold humid night.

Averof, live fire exercise

Averof, live fire exercise

The whole port seemed to light up. Besides bombs, flares, and incendiaries, they were also dropping "parachute" mines. Land-based lookouts, as well as those on AVEROF, were tracing them and recording their landing position for the morning's mine-sweeping operations. Men would run along the deck lighting up smoke screens covering the ship with white smoke. Guns and tracer bullets were shot tracing parabolas in the sky while land-based searchlights lit up wandering aimlessly on the sky until they caught a mass in their sight. In one of those night raids, one mine was descending directly on top of our ship with another one close by. Pandemonium broke out—shouts, orders, and fire hoses intermingled. In the chaos, one of our protective balloons was shot down by our own gun fire while a mass of curling flame floated down to die slowly in the water. Luckily, a gust of wind, at the last minute, blew the other mine a few yards away.

It is worth mentioning that although AVEROF never engaged in surface warfare, because of her armaments she was a formidable floating "gun encasement." Wherever she was assigned, be it a convoy escort operation or the protection of a port, her huge guns were a formidable defender.

It is worth mentioning that although AVEROF never engaged in surface warfare, because of her armaments she was a formidable floating "gun encasement." Wherever she was assigned, be it a convoy escort operation or the protection of a port, her huge guns were a formidable defender.

Cadet Calss of 1941, Mimis 5th L-R

Cadet Calss of 1941, Mimis 5th L-R

Although no ships were lost during those raids, the High Command decided to move AVEROF to the Indian Ocean for safety reasons and for regular maintenance repairs. Also to reinforce convoy escort operations with her big guns since the Germans had commandeered merchant ships and had outfitted them with guns using them as decoys (Q-Ships) to attack other merchant ships.

AVEROF escorted many allied ships, British, Greek, etc. in the Indian Ocean until October 1942, where we returned to Alexandria.

Of course, an additional reason for which the Minister of the Navy, RAdm A. Sakellariou [3] and the Chief of Naval Operations, RAdm E. Kabbadias, wanted AVEROF far from Alexandria was the underlying "revolutionary' mood on AVEROF since the "revolt" in April 1941, when AVEROF was still in Greece. Fortunately, she was saved from being scuttled and was moved to Alexandria [4].

When the decision for AVEROF's departure was announced, Ensign P. Hliomarkakis, who had been the leader of the April revolt, tried to organize another revolt to prevent AVEROF from leaving Egypt. He was spewing the old trite proletariat slogans claiming that by moving AVEROF to India amounted to putting her out of commission in faraway waters, thus preventing her from fighting for Greece's Liberation. His propaganda attracted a few sailors to his cause but none of the cadets or the new Ensigns got involved. As a matter of fact, once the ship's Master At Arms, Ensign G. Drosinos, got wind of the brewing trouble he locked all side arms in a secure storage room. It was a wise move that put an end to that potential revolt.

AVEROF escorted many allied ships, British, Greek, etc. in the Indian Ocean until October 1942, where we returned to Alexandria.

Of course, an additional reason for which the Minister of the Navy, RAdm A. Sakellariou [3] and the Chief of Naval Operations, RAdm E. Kabbadias, wanted AVEROF far from Alexandria was the underlying "revolutionary' mood on AVEROF since the "revolt" in April 1941, when AVEROF was still in Greece. Fortunately, she was saved from being scuttled and was moved to Alexandria [4].

When the decision for AVEROF's departure was announced, Ensign P. Hliomarkakis, who had been the leader of the April revolt, tried to organize another revolt to prevent AVEROF from leaving Egypt. He was spewing the old trite proletariat slogans claiming that by moving AVEROF to India amounted to putting her out of commission in faraway waters, thus preventing her from fighting for Greece's Liberation. His propaganda attracted a few sailors to his cause but none of the cadets or the new Ensigns got involved. As a matter of fact, once the ship's Master At Arms, Ensign G. Drosinos, got wind of the brewing trouble he locked all side arms in a secure storage room. It was a wise move that put an end to that potential revolt.

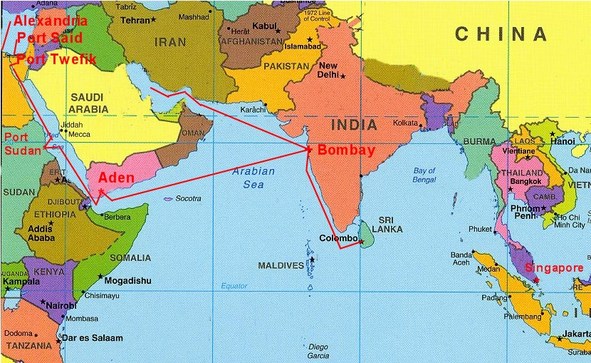

Alex to India, on Averof

On July 1, 1941, a small flotilla of four ships, AVEROF, the submarine KATSONIS—being towed by AVEROF —the Destroyer SFENDONI, and the auxiliary vessel (a floating repair shop) HEPHAESTUS sailed from Alexandria for Port Said, our first stop on our way to India.

We did not stay long in Port Said. Perhaps the only reason we stopped was for the Navy to take care of some unfinished business! Soon after our arrival, captain Kontogiannis arrested Hliomarkakis at gunpoint. He ordered him off the ship and into a waiting motor-boat. Later on, we learned that he was sentenced to eight months in jail and discharged from the Navy.

A few hours later through the Suez Canal, we arrived at Port Tewfiq where we stayed for twenty extremely hot days for maintenance and repairs. Port Tewfik was also being bombed by the Germans. One night the liner GEORGIC [5], carrying families and servicemen on leave, was hit by a bomb and caught on fire. Her captain tried to beach her in shallow waters, but due to steering malfunction, I suppose, to our horror, we saw her coming directly toward us. The general alarm "collision with a burning ship" was sounded on AVEROF. The hoses came out and the fire brigades were ready when GEORGIC suddenly changed direction. She bounced off a merchant marine ship and beached in the shallows. We immediately launched our lifeboats plucking out of the water several of GEORGIC's passengers who had jumped, some burning, into the sea. GEORGIC was burning for eight days.

We did not stay long in Port Said. Perhaps the only reason we stopped was for the Navy to take care of some unfinished business! Soon after our arrival, captain Kontogiannis arrested Hliomarkakis at gunpoint. He ordered him off the ship and into a waiting motor-boat. Later on, we learned that he was sentenced to eight months in jail and discharged from the Navy.

A few hours later through the Suez Canal, we arrived at Port Tewfiq where we stayed for twenty extremely hot days for maintenance and repairs. Port Tewfik was also being bombed by the Germans. One night the liner GEORGIC [5], carrying families and servicemen on leave, was hit by a bomb and caught on fire. Her captain tried to beach her in shallow waters, but due to steering malfunction, I suppose, to our horror, we saw her coming directly toward us. The general alarm "collision with a burning ship" was sounded on AVEROF. The hoses came out and the fire brigades were ready when GEORGIC suddenly changed direction. She bounced off a merchant marine ship and beached in the shallows. We immediately launched our lifeboats plucking out of the water several of GEORGIC's passengers who had jumped, some burning, into the sea. GEORGIC was burning for eight days.

Averof: Christos, Periklis, Costas (L to R)

Averof: Christos, Periklis, Costas (L to R)

We left Port Tewfiq around July 20, 1941, and arrived at Port Sudan at the end of the month during scorching hot weather. At that time, Mimis was confined in the ship’s sick bay with tonsillitis. But he took a turn for the worse because the ship’s sick bay was on the side exposed to the sun. As a result, he suffered heatstroke. Fortunately, they immediately put him in ice and transferred him to the British hospital on shore where he recovered. Unfortunately, three other sailors did not survive.

Captain Kontogiannis was concerned about Mimis’ welfare. When Mimis was released from the hospital he saw to it that he was sent to a British convalescing center in Khartoum. At the end of September, when Mimis was well enough to travel, he returned to Alexandria where he boarded AETOS which was going to meet with AVEROF in Bombay.

Once aboard AVEROF, he was officially sworn into the Greek Navy on November 8, 1941. He was supposed to have taken the oath on September 21, 1941, on his 17th birthday, but it was postponed because at that day he was hospitalized in Sudan.

-------- from Mimis' diary -------------------------------------------------------

Khartoum Convalescing Camp (after my release from the hospital in Port Sudan to convalesce from the heatstroke I had suffered):

A pleasant cool breeze was blowing down from the mountains entering the ward through the thatch of the bamboo walls. I was lying on my bed looking out the window, in a semi-conscious state, with half-closed eyes, when I noticed in the distance two Arabs on their camels coming closer and closer to the camp.

After a while, I see them entering the ward. They talked to the doctor on duty who nodded in my direction. They looked at me and came to my bed. They were tall, fit, and looking handsome in their white burnooses.

“Good Morning! We heard that a compatriot of ours was in the camp and we came to wish him a fast recovery.”

“How are you, friend?” they said in Greek, with a Cretan accent!

“I am fine, thank you,” I said, completely puzzled.

“Are you Cretans? “ How did you hear about me?” I asked.

“We hear everything,” they replied.

"How are you doing? Do you feel better? " they inquired.

"Yes, I feel fine. When am I going back to my ship?" I replied.

“Well, that's good." " O.K., Goodbye and Godspeed,” they said.

" Thank you," I replied.

“We've got to go, now,” they said.

"But, so soon?” I said.

“Yes, we have work to do," they replied.

“What kind of work?” I inquired, but they did not answer. Instead, they gave me a heartfelt handshake, wished me well and took their leave.

Through the window, I saw them on their camels receding in the vastness of the scrubby wasteland and finally fading away, like a dream.

“You did not eat your butter, again,” thundered the doctor on duty angrily, jolting me out of my reverie.

“Eat it, if you don’t want to die,” he continued. And then, he turned to the patient on the bed next to me.

The sad truth was that every day someone in the camp passed away. So, with no farther ado, I quietly spread lots of marmalade on the butter, so I could not see it, and I swallowed the whole slab!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Another casualty of the hot weather was the (long) trousers. "Shorts" became the "fashion," although they were not readily accepted. However, after the initial "shock" and the inevitable teasing and jaded, acidic, and largely humorless jokes among the officers and the ratings, they became the norm. Incidentally, it was rumored that even Toumbas, reluctantly, succumbed to the new "fashion" after he saw his British counterparts wearing them!

Captain Kontogiannis was concerned about Mimis’ welfare. When Mimis was released from the hospital he saw to it that he was sent to a British convalescing center in Khartoum. At the end of September, when Mimis was well enough to travel, he returned to Alexandria where he boarded AETOS which was going to meet with AVEROF in Bombay.

Once aboard AVEROF, he was officially sworn into the Greek Navy on November 8, 1941. He was supposed to have taken the oath on September 21, 1941, on his 17th birthday, but it was postponed because at that day he was hospitalized in Sudan.

-------- from Mimis' diary -------------------------------------------------------

Khartoum Convalescing Camp (after my release from the hospital in Port Sudan to convalesce from the heatstroke I had suffered):

A pleasant cool breeze was blowing down from the mountains entering the ward through the thatch of the bamboo walls. I was lying on my bed looking out the window, in a semi-conscious state, with half-closed eyes, when I noticed in the distance two Arabs on their camels coming closer and closer to the camp.

After a while, I see them entering the ward. They talked to the doctor on duty who nodded in my direction. They looked at me and came to my bed. They were tall, fit, and looking handsome in their white burnooses.

“Good Morning! We heard that a compatriot of ours was in the camp and we came to wish him a fast recovery.”

“How are you, friend?” they said in Greek, with a Cretan accent!

“I am fine, thank you,” I said, completely puzzled.

“Are you Cretans? “ How did you hear about me?” I asked.

“We hear everything,” they replied.

"How are you doing? Do you feel better? " they inquired.

"Yes, I feel fine. When am I going back to my ship?" I replied.

“Well, that's good." " O.K., Goodbye and Godspeed,” they said.

" Thank you," I replied.

“We've got to go, now,” they said.

"But, so soon?” I said.

“Yes, we have work to do," they replied.

“What kind of work?” I inquired, but they did not answer. Instead, they gave me a heartfelt handshake, wished me well and took their leave.

Through the window, I saw them on their camels receding in the vastness of the scrubby wasteland and finally fading away, like a dream.

“You did not eat your butter, again,” thundered the doctor on duty angrily, jolting me out of my reverie.

“Eat it, if you don’t want to die,” he continued. And then, he turned to the patient on the bed next to me.

The sad truth was that every day someone in the camp passed away. So, with no farther ado, I quietly spread lots of marmalade on the butter, so I could not see it, and I swallowed the whole slab!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Another casualty of the hot weather was the (long) trousers. "Shorts" became the "fashion," although they were not readily accepted. However, after the initial "shock" and the inevitable teasing and jaded, acidic, and largely humorless jokes among the officers and the ratings, they became the norm. Incidentally, it was rumored that even Toumbas, reluctantly, succumbed to the new "fashion" after he saw his British counterparts wearing them!

Christos on Averof

Meanwhile, in Port Sudan, the hot weather continued unabated. Everybody had problems with skin heat rash, the constant sweating made it impossible to get rid of it. And to avoid more heatstroke casualties the work schedule was adjusted so that we started work at daybreak, worked for a few hours, then stopped and resumed work after sunset, until midnight. Even the coaling was done at night—a dirty and labor intensive job from which none was excused, except the Captain and the first Engineer.

Barges loaded with coal would sidle up to Averof, two on each side. Then, Averof's cranes would lower big canvas tarps onto the barges where their crews would stretch them on the deck and load them with coal. Then they would secure the corners of the tarps on the hook of the cranes. The cranes would lift the loaded tarps and deposit them on AVEROF's deck.

AVEROF's Executive Officer was in charge of the coaling operation with the officers acting as coaling-gang leaders. The cadets' job was shoveling the coal dumped on the deck into hoppers leading to the coal-storage in the bowels of the ship. Sometimes we had to carry the coal in zembils (straw baskets) on our backs while the ship’s Music detachment was playing various Navy marches, to imbue patriotism and stiffen the spine. From then on, whenever I heard those marches I was reminded of those days on AVEROF, shoveling coal. And if loading 1,500 tons of coal was not bad enough, trying to get rid of the coal-dust that had penetrated every nook and cranny of the ship was an equally hard and dirty job that was prolonging our "spitting black" for days after inhaling that stuff. It is understood that Navy life is not meant to be a perpetual entertainment, but "ship coaling," even with the band playing is not fun.

Barges loaded with coal would sidle up to Averof, two on each side. Then, Averof's cranes would lower big canvas tarps onto the barges where their crews would stretch them on the deck and load them with coal. Then they would secure the corners of the tarps on the hook of the cranes. The cranes would lift the loaded tarps and deposit them on AVEROF's deck.

AVEROF's Executive Officer was in charge of the coaling operation with the officers acting as coaling-gang leaders. The cadets' job was shoveling the coal dumped on the deck into hoppers leading to the coal-storage in the bowels of the ship. Sometimes we had to carry the coal in zembils (straw baskets) on our backs while the ship’s Music detachment was playing various Navy marches, to imbue patriotism and stiffen the spine. From then on, whenever I heard those marches I was reminded of those days on AVEROF, shoveling coal. And if loading 1,500 tons of coal was not bad enough, trying to get rid of the coal-dust that had penetrated every nook and cranny of the ship was an equally hard and dirty job that was prolonging our "spitting black" for days after inhaling that stuff. It is understood that Navy life is not meant to be a perpetual entertainment, but "ship coaling," even with the band playing is not fun.

Averof in rough waters in the Persian Gulf

Averof in rough waters in the Persian Gulf

AVEROF, being a juggernaut of the WW I era, was one of the few ships, if not the only one, using coal as fuel. I still remember the curious looks of a group of visiting Dutch officers in Bombay who came aboard to see "a coal-fueled ship from the past!" I am glad they did not ask for a "coaling" demonstration!

We completed the scheduled maintenance and departed Port Sudan for Aden [6]. By then Captain S. Matesis had taken over as skipper.

With the thermometer reading 86 F degrees, we were glad to get moving again. The headwind made us feel cooler although the temperature kept rising to 95 F degrees, and the forecast was that by the time we reach Bombay we would be well cooked!

We got out into the Red Sea heading south with land visible on both sides, most of the time. We passed Thor, a small island and a group of bare rocky islands, and after miles of scarcely inhabited but picturesque coastal landscape, on the African side, the minarets of Mocha, a relatively large town on the Arabian peninsula, came to view in front of us in the distance. We left Mocha to our left and headed for the straits of Bab el Mandeb, the Gate-of-Tears. Perhaps the straits got their name from stories about mariners sailing through them being reduced to tears; those going south for their deliverance from the infernal heat, and for the northbound for the thermal ordeal awaiting them!

Once we crossed the strait, a narrow passage about ten miles in width between Perim island and Africa, we entered the Gulf of Aden. It was like entering paradise—there was a pleasant cool breeze blowing making the heat tolerable. This sudden change in weather seemed to re-energize the whole ship, as well as the fish in the sea that looked like was swarming around us!

After a few hours and countless long choppy swells hitting the old lady on the side, every slap raising a salty mist enveloping everyone on deck, with a sharp turn of the rudder to port we arrived in Aden where we immediately began the usual port routine. Aden was a different kind of town. It vaguely resembled Monemvasia with its old fortifications and being connected with Arabia by a narrow isthmus—and the comparisons stop there. From my guard post on AVEROF's main deck, the spectacle before me was sufficient to hold my attention, although not much different from that on the docks of Tewfik or Port Sudan. Several small ships of various and rather strange shapes were moored farther up unloading troops, animals, passengers, and supplies. And even more lay in the distance in what looked like a cluster of three small, possibly abandoned, warship. On the docks, the activity looked chaotic; semi-clad peddles and stevedores milling around, wagons drawn by oxen with long curved horns, heavily caparisoned donkeys with tassels and embroideries, camels, and soldiers guarding something covered with canvas tarps. There were also our sailors attending to the ship's various needs while well-dressed Englishmen and British officers were conducting business with our Executive Officer and with Arabs in long flowing white robes.

Our stay in Aden was short and uneventful. We got some provisions and without fanfare slipped out of the port and back in the Gulf of Aden steaming at standard speed toward Bombay.

We completed the scheduled maintenance and departed Port Sudan for Aden [6]. By then Captain S. Matesis had taken over as skipper.

With the thermometer reading 86 F degrees, we were glad to get moving again. The headwind made us feel cooler although the temperature kept rising to 95 F degrees, and the forecast was that by the time we reach Bombay we would be well cooked!

We got out into the Red Sea heading south with land visible on both sides, most of the time. We passed Thor, a small island and a group of bare rocky islands, and after miles of scarcely inhabited but picturesque coastal landscape, on the African side, the minarets of Mocha, a relatively large town on the Arabian peninsula, came to view in front of us in the distance. We left Mocha to our left and headed for the straits of Bab el Mandeb, the Gate-of-Tears. Perhaps the straits got their name from stories about mariners sailing through them being reduced to tears; those going south for their deliverance from the infernal heat, and for the northbound for the thermal ordeal awaiting them!

Once we crossed the strait, a narrow passage about ten miles in width between Perim island and Africa, we entered the Gulf of Aden. It was like entering paradise—there was a pleasant cool breeze blowing making the heat tolerable. This sudden change in weather seemed to re-energize the whole ship, as well as the fish in the sea that looked like was swarming around us!

After a few hours and countless long choppy swells hitting the old lady on the side, every slap raising a salty mist enveloping everyone on deck, with a sharp turn of the rudder to port we arrived in Aden where we immediately began the usual port routine. Aden was a different kind of town. It vaguely resembled Monemvasia with its old fortifications and being connected with Arabia by a narrow isthmus—and the comparisons stop there. From my guard post on AVEROF's main deck, the spectacle before me was sufficient to hold my attention, although not much different from that on the docks of Tewfik or Port Sudan. Several small ships of various and rather strange shapes were moored farther up unloading troops, animals, passengers, and supplies. And even more lay in the distance in what looked like a cluster of three small, possibly abandoned, warship. On the docks, the activity looked chaotic; semi-clad peddles and stevedores milling around, wagons drawn by oxen with long curved horns, heavily caparisoned donkeys with tassels and embroideries, camels, and soldiers guarding something covered with canvas tarps. There were also our sailors attending to the ship's various needs while well-dressed Englishmen and British officers were conducting business with our Executive Officer and with Arabs in long flowing white robes.

Our stay in Aden was short and uneventful. We got some provisions and without fanfare slipped out of the port and back in the Gulf of Aden steaming at standard speed toward Bombay.

Aden - Bombay - Persian Gulf - Ceylon

Aden - Bombay - Persian Gulf - Ceylon

After sailing about two thousand uneventful miles from Alexandria, we arrived in Bombay in the middle of September and went directly to dry-dock for a few days.

Bombay was a typical WW II colonial army/navy town teeming with people, animals, brothels, spies, hucksters and street magicians of all descriptions—from the grotesque to macabre—and clouds of flies feasting on fetid garbage and the ubiquitous cow and elephant dung piles.

After another coaling and toward the end of September 1941, we went out on our first mission escorting a convoy of five navy transports to the Persian Gulf and back to Bombay.

A couple of days before our departure, my old "friend" (the Destroyer) AETOS, from my "DURENTA 7" days, dropped anchor in Bombay. She did not stay long, but I remember the day she passed by AVEROF on her way to Ceylon with Commander Toumbas on her bridge. She paused to salute the old warrior (AVEROF), with a thunderous "AERAAAA." [7]

Besides the pride and joy I felt seeing AETOS going by and hearing her crew's thunderous salutation, for me it was a double joy. I knew one of those voices was my brother Mimis' whom I had not see for months after he got sick and sent to convalesce in Khartoum.

Just before Christmas of 1941, we sailed from Bombay toward Singapore escorting five ships. South from Ceylon, we met the British cruiser GLASGOW. At that point, four of the ships detached and went with her. And we continued with the fifth toward the Gulf of Ceylon arriving at the port of Colombo sometime between Christmas and New Year's.

I remember that we, the cadets, spent New Year's Eve 1942, in a British cruiser's midshipman's lounge among British cadets and junior officers. It was a long and boisterous night, for British standards. At some point before midnight the Captain came in. "A toast all around, gentlemen," the Captain said, and once we were all standing with glasses re-filled or topped up, the Captain paused in thought for a moment, then said, "to the VICTORY, gentlemen!" "To the VICTORY," we all chorused enthusiastically. And after a couple of more libations to the King and Country, the Captain departed as a small army of orderlies flamboyantly carrying platters of Ham, Roast Beef, fried chicken, gravy, several bottles of wine and huge canisters of black tea entered the lounge. A memorable feast that made the war temporarily go away.

I also remember that one evening Lt. Commander E. Mpoundouris, our Dean of Students, took Costas [Notaras], Mimis, and me to a famous local hotel, the "Grand Oriental Hotel " for dinner. When we entered the hotel's main dining room the orchestra, which apparently recognized our uniforms, began playing the popular Greek song of the day: "Δυο Πρασινα Ματια" (Two green eyes).

We waltzed through the dining room, humbly acknowledging the applause, as we were ushered to a table in the middle. A couple of British and Allied officers came over to exchange pleasantries and a group of British civilians began singing songs mocking "Il Duce," Benito Mussolini. Outside, the veranda was besieged with rowdy and rather drunken military colonials-- Indian, Rhodesian, South African, Aussies and NZs.

And if that was not enough of a pleasant surprise, the waiter, in typical Indian attire, while taking our order, smiled and said "sorry, no gyros for the heroes," and "sorry again, no ouzo, only rum." Undoubtedly, Greece's 1940-41 epic victory against the Italians in the Albanian front had to do something with that display of public affection for our country around the world.

Bombay was a typical WW II colonial army/navy town teeming with people, animals, brothels, spies, hucksters and street magicians of all descriptions—from the grotesque to macabre—and clouds of flies feasting on fetid garbage and the ubiquitous cow and elephant dung piles.

After another coaling and toward the end of September 1941, we went out on our first mission escorting a convoy of five navy transports to the Persian Gulf and back to Bombay.

A couple of days before our departure, my old "friend" (the Destroyer) AETOS, from my "DURENTA 7" days, dropped anchor in Bombay. She did not stay long, but I remember the day she passed by AVEROF on her way to Ceylon with Commander Toumbas on her bridge. She paused to salute the old warrior (AVEROF), with a thunderous "AERAAAA." [7]

Besides the pride and joy I felt seeing AETOS going by and hearing her crew's thunderous salutation, for me it was a double joy. I knew one of those voices was my brother Mimis' whom I had not see for months after he got sick and sent to convalesce in Khartoum.

Just before Christmas of 1941, we sailed from Bombay toward Singapore escorting five ships. South from Ceylon, we met the British cruiser GLASGOW. At that point, four of the ships detached and went with her. And we continued with the fifth toward the Gulf of Ceylon arriving at the port of Colombo sometime between Christmas and New Year's.

I remember that we, the cadets, spent New Year's Eve 1942, in a British cruiser's midshipman's lounge among British cadets and junior officers. It was a long and boisterous night, for British standards. At some point before midnight the Captain came in. "A toast all around, gentlemen," the Captain said, and once we were all standing with glasses re-filled or topped up, the Captain paused in thought for a moment, then said, "to the VICTORY, gentlemen!" "To the VICTORY," we all chorused enthusiastically. And after a couple of more libations to the King and Country, the Captain departed as a small army of orderlies flamboyantly carrying platters of Ham, Roast Beef, fried chicken, gravy, several bottles of wine and huge canisters of black tea entered the lounge. A memorable feast that made the war temporarily go away.

I also remember that one evening Lt. Commander E. Mpoundouris, our Dean of Students, took Costas [Notaras], Mimis, and me to a famous local hotel, the "Grand Oriental Hotel " for dinner. When we entered the hotel's main dining room the orchestra, which apparently recognized our uniforms, began playing the popular Greek song of the day: "Δυο Πρασινα Ματια" (Two green eyes).

We waltzed through the dining room, humbly acknowledging the applause, as we were ushered to a table in the middle. A couple of British and Allied officers came over to exchange pleasantries and a group of British civilians began singing songs mocking "Il Duce," Benito Mussolini. Outside, the veranda was besieged with rowdy and rather drunken military colonials-- Indian, Rhodesian, South African, Aussies and NZs.

And if that was not enough of a pleasant surprise, the waiter, in typical Indian attire, while taking our order, smiled and said "sorry, no gyros for the heroes," and "sorry again, no ouzo, only rum." Undoubtedly, Greece's 1940-41 epic victory against the Italians in the Albanian front had to do something with that display of public affection for our country around the world.

L-R: I. Lagonikas, Christos, unknown in India-- Teasing an avian denizen

L-R: I. Lagonikas, Christos, unknown in India-- Teasing an avian denizen

Periodically, in between missions and the maintenance of the ship's boilers, groups of about twenty men—sailors, officers, and petty officers—were sent for R & R (Rest and Recreation) to Deolali, a "resort" facility operated by the British Navy in the hills about a hundred fifty miles northeast of Bombay.

The "resort," open to other Allies, as well, was in the vicinity of several "transit" camps, including a hospital for British troops destined for operations in the India-Burma-China theater of war and for those returning from Burma and other parts of India on their way home.

Naturally, the "resort" was off limits to those in the camps. And as I later found out, although the "resort" resembled the camps, the difference was like night and day. Consequently, my fond memories of Deolali were (and still are) in stark contrast with the memories of those who passed through the camps. For the British troops who spent time there, Deolali had a rather negative reputation. It was known as a place of boredom, illness, and severe mental problems. As a matter of fact, for the British, "gone Deolali" meant someone had gone crazy or was mentally disturbed.

My group's Deolali "dream vacation" began when we were dropped at the Bombay train station, a magnificent Victorian building, and one of the indisputable benefits of British colonialism. We arrived at the time when countless dabbawalas (food delivery boys), on foot or riding bicycles, were fanning out in a chaotic fashion to deliver tiffing boxes of homemade lunches. We entered a cavernous hall packed with people yelling and screaming and hands waving in the air. Thus, from the orderly life aboard the ship we found ourselves in the midst of a noisy and frenetic place; trains, people, cows, soldiers, flies, magicians, more flies, beggars, carts, more cows ... and hordes of semi-clad barefooted street urchins swarming us, arms extended and palms up, begging: “Backsheesh, Sahib”—and trying to hire themselves as porters. Thus, for half a rupee(?), not only did I have my bag carried but from being a young officer, a mere Ensign of no importance, I was instantly elevated to ... “Sahib!”

In anticipation of the four-hour trip and not knowing what accommodations were on the train, we thought it would be prudent to take care of our physical needs before boarding; what a horrible mistake! Half of the group stayed put keeping an eye on our luggage—that is, on our newly hired porters from absconding with them—while about five of us headed for the "restroom." Well, that "restroom" defied description. Besides the horrid stench aggravated by the humid summer-like Indian weather, the flies, and the wet floor, the facility was primitive and beyond disgusting. A ten-meter-long and half-meter-wide concrete ditch, separated into stalls by one-meter-tall walls without doors, filled with a stew of feces and urine—men and women squatting over it, disturbing the flies feasting on that filth. And no water in sight for flushing it or for washing hands.

With a quick about-face, wildly flailing our arms in the air to ward off flies buzzing about with their hairy legs dipped in feces, we exited the room before being asphyxiated by the noxious odors and joined our party, trying to expunge that revolting image from our brain.

"Backsheesh" accounts settled, me and the other AVEROF newly anointed "Sahibs," following our "porters," pushed, shoved, and squeezed our way through a churning sea of people, animals, baggage, and piles of rubbish to get to our train. The train was a sight to behold! We got into it, whereas the hordes of "untouchables" and their possessions were on it—crammed on the hot steel roofs or hanging from the rust-pocked handrails—and kids hanging from the windows begging for money. if I had not seen them when I boarded the train, I would have thought that they were on stilts.

Our coach was full but not crowded. Just Indian and Allied officers and upper-caste civilians with their servants taking care of the children, most of them resembling miniature Maharajas in corpulence and attire; in stark contrast to the kids hanging outside the windows. Well, "c'est la vie!"

We all had comfortable seats, albeit the wooden-bench variety. Of course, luggage filled the aisle in the middle of the car between the two rows of benches which made it quite a challenging obstacle race to visit the restroom. That is, a 4'x4' foot enclosure at the end of the car with just a hole in the floor, with a clear view of the railroad ties speeding in the opposite direction below your feet. And God only knows what was going on in the second class coaches or on the roofs. The air inside the car, despite the open windows, was hot and stifling, a mixture of sweat, curry, and rotten food. Although it improved considerably once we got going.

With a shriek blow of the train's whistle, the clank of the couplings, and a jolt our Deolali trip began. Instinctively, I turned my head to take a last look through the window, while waving away a fly from landing on my hair, when I saw a terrifying scene unfolding: A tsunami of desperate humanity rushing toward the train. Men, women, and children running alongside the tracks trying to get a hold of the ever faster-moving train. Some made it, some fell off, and the rest gave up the chase huffing and puffing like cheetahs outrun by the prey. Were there any casualties? Who knows! And worst yet, it was apparent that nobody cared!

We moved at a good clip being serenaded by the clack-clack, clickety-clack of the wheels while the scenery outside was constantly changing with every sharp turn; from lush green valley to semi-desert, from flat terrain to horrifying drops down to rugged canyons, and from horrendous precipices to deep jungle gorges. To this day I wonder how the "outsiders," the people on the roofs and those hanging outside, using unimaginable nook and crannies for a foothold, did not fly off the train or did not fry being exposed to the scorching Indian sun!

After about four hours we arrived in Deolali. Although the train station was considerably smaller than the one in Bombay, the scenery was equally, if not more, chaotic. Even before the train came to a complete stop, people were clambering down from the roofs. Animals and packages were thrown, pushed, or dropped to the ground. The privileged kids in our coach were guided tenderly by their nannies and the infants were handed over people's heads and passed carefully to a waiting servant—whereas the children of the plebeian masses were tossed from the roofs to someone's extended arms on the platform.

However, unlike our experience boarding the train in Bombay where we had to push our way through a sea of people and animals, here, as guests of the (British) Crown, we found ourselves under the "protection" of a British-Indian detachment waiting for us. It acted like "Moses," parting the sea of people and animals, leading us to "the promised land"--a somewhat comfortable looking military vehicle for the short ride to the resort.

On the way, we were treated to some more exotic adventures, as far as we were concerned, but a huge nuisance for the driver who had to deal with them regularly. As we rounded a curve, the bus came to an abrupt stop, while the billowing dust enveloped us. Fanning ourselves and squinting at the plume of dust we saw in the shimmering distance a half-necked fakir brandishing a rather lethal-looking stick coming toward us. He began banging on the sides of the bus with his stick and demanding, you guessed it, “baksheesh!”

But having already been anointed "Sahibs" at the Bombay train station, and being in the relative safety of “His Majesty’s” vehicle, and, more importantly, still carrying our sidearms, none of us was sympathetic towards a wild self-appointed "toll collector" demanding baksheesh to let us pass. So, he got nothing but scornful looks and snide comments. And with a few more gratuitous bangs on the side of the bus with his stick, accompanied with several less than holy hand-gestures and loud curses, he retreated to the shade under a tree assuming the lotus position, legs crossed and arms folded, waiting for the next passing conveyance to attack.

Relieved and mostly amused by the incident we were ready to go. But the bus did not move. While we were preoccupied with the fakir another "holy entity" blocked our way; a Brahman bull! He had plopped himself in the middle of the road and despite our irreverent and “politically incorrect” yelling and shouting, he would not budge. He kept staring at us with that characteristic bovine indifference regardless of our lack of reverence. Eventually, we had to drive off the road around him. However, unlike the fakir, he did not shout or gesticulate at us. He did not seem to be bothered at all—he looked impressive in his state of absolute divine serenity!

With the fakir and the bull being the hot topic of conversation, and the butt of some irreverent jokes, before long, we were let out at a "dak bungalow," a typical Indian Government structure. In essence, it was a big hall that served as the "reception" facility, whose center was occupied by a wooden life-size sculptured figure of some rather grotesque looking deity. And there was where our dream vacation really began.

Deolali was an idyllic place in every aspect, partly Indian and partly English, with abundance of greenery and spectacular scenic vistas of forested hills. The weather was hot and sultry, the locale rural, and the mosquitoes ... big as elephants! Of course, that's nothing if you consider the ever-present danger of crossing paths with a cobra, a scorpion, or being dive-bombed by a hawk to steal your lunch—and gargantuan vermin was a common sight.

Luckily, in the residence hall and at the club, nets, huge electric ceiling- and pankah-fans, complete with pankah boys in turban thrashing away, made the heat comfortable, if not bearable, and kept the mosquitoes at bay. The hawks, when they were not stealing lunches, were taking care of the scorpions and the vermin—I never had my lunch stolen by a hawk, because I never ate outdoors, as some British did. And at night we were lulled to sleep counting the mosquito kamikaze-attacks on our mosquito bed nets.

Cobras, however, was a different story! Since they had mystical powers over the natives, pestering or killing one would have been the modern-day equivalent of an "international incident of foreign aggression!" Fortunately, my encounter with a cobra was from a safe distance, in a crowded street in Bombay! It cost me a couple of coins to see one coming up from a snake charmer's basket—a mesmerizing and rather repulsive spectacle!

Notwithstanding the heat, the mosquitoes, and the cobras, my stay in Deolali was pleasant and very relaxing; hobnobbing with British "servants of the Empire"—R.N. officers, H.M.'s Highlanders, ANZACs (Australian and New Zealanders), South Africans, Rhodesians and others—in the opulence of the Officers' Lounge being treated like royalty, where the conversation revolved more about Polo, Golf, and Tennis rather than Rommel, Auchinleck, or El Alamein! In short, the overall ambiance was something new for us, a combination of the excesses of British aristocracy and the pleasures of colonial India. There is where I saw the splendor of the British Empire in all its "glory."

In addition to the Sepoys—Indian natives serving in the British army—there was an army of turbaned servants; valets, barbers, porters, shoe-shine boys, and cloth-washing women. They were everywhere, in the sleeping quarters, the Club House, the Billiards Rooms, the gardens, and at the rarely used, because of the heat, Tennis, Rugby, and Racket courts, ready to render their services.

Some orderlies wore a small sword, slung short from their waste. It reminded me of my "Cadet's Dagger" the Turkish officer stole from me when we landed in Turkey on our way to Alexandria.

Besides the plentiful food and the cocktail mini-parties at the club, the cool hours of the day were spent on all kinds of leisurely activities such as falconry! Well, a modified form of falconry! That is, teasing the hawks by throwing in the air bones or pieces of meat from the dumpster and watching them dive to catch them mid-air. Of course, the elephant vs. camel races were one of the favorites. They did not require any physical exertion on our part except having a strong stomach to down those cool but spicy beverages freely served by roving servants in our private, cordoned off and sun protected section of the field. Tennis, of course, was the "un-required" but "obligatory" activity for proclaiming our European elan and sophistication. However, after a couple of volleys, we would get drenched with sweat and rush back to our living quarters for a refreshing shower. And, at least once during our stay—and that was enough—we had to make the arduous trek to the "rock," in the hottest time of the day. The "rock" was a massive rock, in the periphery of the resort, heated by the sun to the point where we could fry eggs on it, for the day's ritualistic tiffin (lunch)!

Another pastime was the escorted visits to the town. It was a diversion from the dreamy life at the resort. The town ambiance was a scaled-down version of Bombay; the good sections and the bad sections, the roaming cows, and the feasting flies on the cow dung; the red light district offering a cornucopia of forbidden pleasures, and the upper caste section of the town; the rich store owners and the begging children; the usual street merchants and the Bazaar. The Bazaar was no different than other bazaars but it seemed to have many more produce stands with delicious looking and hard to resist fresh fruits. Unfortunately, though, once we were informed that some (most?) of the fruit was grown in sewage farms their appeal instantly disappeared.

Incidentally, the same happened when our guide took us to the red-light district. The merchandise looked as delicious and as juicy as the fruit in the bazaar; incredibly beautiful young women with exquisite exotic features, some hardly over the age of consent! But looking at the surroundings and the slime bubbling up from the open sewers in the middle of the street made any youthful urges we may have had to be instantly killed—perhaps a blessing in disguise. It also killed the real or mostly imaginary tails of conquests of fetching young ladies span by men following the return from the town visits.

On a happier note, strolling down the street we came across a loud, sleigh-of-hand magician entertaining the crowd with levitation and a trick involving a coin and a chicken. We stood off to the side trying not to distract the crowd with our presence, and with hands in our pockets to discourage any pickpockets working independently or with the magician, and trying to look nonchalantly at the magician's antics.

Perhaps, due to our western culture which makes light of magic, we were not as awed by the magician's levitation as the rest of the crowd, or about the disappearing coin; seemingly swallowed by the chicken and then retrieved from the chicken's other end. Nevertheless, his performance was awe-inspiring and highly entertaining. Naturally, we joined the rest of the audience in make-believe puzzlement, patronizingly declining the magician's calls to bear him out to provide credence to his machinations. And as he continued his routine, we dropped a few coins in the can held by his partner working the crowd and resumed our strolling down the street.

However, the highlight of our stay was an unscheduled, and certainly unexpected, officers only, invitation to a banquet in honor of a visiting delegation of high British and Indian officials. Alas, we did not have with us the appropriate for the occasion uniform! But the "Deus ex machina" (Ο απο μηχανης Θεος), in the person of the Appuhamy, the Hospitality chief(?), saved the day. He loaned us clean British uniforms, which were, and still are, practically identical to the Greek/British uniforms; some a tad oversized and a bit less fancy than the ones worn by our British counterparts.

The whole affair was like a story out of "Shahrazad's 1001 Arabian Nights!" An introduction to the fabled mysteries and allures of the Indian subcontinent. We were picked up from the residence hall in an open gilded carriage, drawn by a richly caparisoned elephant—an immense animal with huge tusks—for the less than hundred yards to the club located at the center of the "resort." The building looked unusual in its design but beautiful in its décor—in stark contrast to the gleaming white-marble grandeur of the ancient Greek buildings.

Upon arrival, white-turbaned torch-bearers in white uniforms and gloves formed a reception line and footmen helped us down from the carriage. Then, a colorful four-man honor guard, swords drawn, in shawls and red turbans escorted us, two in front and two in the back, to the reception room through a long corridor whose walls were covered with murals of ethereal beauties, jungle animals, hunting scenes, portraits of past and present British Royals, battles of another day, and mirrors to no end.

The reception was a kaleidoscope of Allied uniforms; swords, rubies, feathers, and more mirrors. Deolali's beau monde, bejeweled upper caste notables, highfalutin British officers bedizened with resplendent military medals, and dignitaries of all descriptions, some with upturned slippers, were in attendance. We got in the reception line and after the usual introductions and compliments were over we were all ushered into the adjacent room, followed by the dignitaries, where the dinner tables were laid out in splendid décor attended by, you guessed it, another army of white-gloved and white-turbaned stewards and pages bustling about to wait on us.

After the physical and the musical "Procession of the Nobles" were finished, and they were standing in front of their appointed seats, three loud cheers: "Long live the King," followed by a libation to the king's health, given of course, by the British present, signaled the beginning of a gastronomical extravaganza beyond fantastic in quantity and variety of foods and spirits, even though we were in the midst of a raging World War. "Food shortage" or "rationing" were foreign words that nobody knew how to pronounce, much less talk about them! And a colonial band enlivened the party with patriotic/popular British tunes of the day. Ah, music, the crowning embellishment of a Lucullan feast!

Fortunately, there were some fair ladies in the milieu, both British and native, who graced with their elegance the banquet more than any of the exquisite table ornaments or the headdress panaches of the portly bejeweled dignitaries. Their aristocratic necks were laden with diamond and emerald necklaces and their arms and fingers sparkled with diamond rings and gold bracelets. There was enough gold and precious stones in the room to put a ship's company in high style for the duration of the war and beyond! Needless to say, I have never seen so many and so big diamonds, rubies, and emeralds in my life as I did that night.

In between the fustian speeches and the stewards circling the room carrying trays of all kinds of delicacies, we began swapping war stories. Next to me was sitting a British colonial army lieutenant from Rhodesia who regaled me with horrific stories about Japanese brutality, wading through ankle-deep mud, malaria, blood-sucking leeches, dysentery, typhus, and infantry's relentless hacking through the hot and humid India-Burma jungles. Listening to him, I thanked my lucky stars for joining the navy instead of following in my father's footsteps [he was an Army Colonel].

After dinner, we adjourned to the candlelit veranda overlooking a lush garden dominated by an imposing water-fountain inhabited by a troop of monkeys scavenging for tidbits of food and causing a spectacle with their antics. It was also illuminated by the ambient light of torches carried by uniformed sepoys on horses, while they were putting them through their paces, as peacocks nonchalantly strutted along the periphery of the lawn. The night was cool and pleasant. And as if on cue, when the dignitaries finally joined us on the veranda, the much talked about fireworks display began. With a loud "BOOM" the pitch black sky exploded into brilliant waterfalls of crackling fire cascading down and filling the night air with acrid smoke. It was a rather spectacular affair, but after one has experienced "real" fireworks it's hard to be bedazzled by such a benign display of innocuous pyrotechnics.

Incidentally, the monkeys did not appear to be bothered much by the horses, the peacocks, the loud noise, or the flashes of the fireworks. Apparently, they were used to it. And despite the apparent valiant effort of the attendants on the ground to shoo them away, they still managed to come under the veranda to grab the nuts and the fruit morsels we were throwing to them, thus adding to our amusement. And, I suppose, our laughter and our "Ahs and Ohs" exclamations were entertaining to the monkeys!

At about 10:00 pm. the fireworks were over and the "exit ceremony" began; military salutes, handshakes, curtsies, thanks and compliments were given all around. Elephants, cars, and carriages were summoned, and we took our leave.

And, like all dreams, this particularly pleasant one came to an end on a lovely morning day. After breakfast, we packed our belongings and, unceremoniously, were ushered to the main hall to wait for our turn to be transferred to the train station; thus we were instantly demoted from exalted "Sahibs," taxied to the tennis courts and the tea parties on rickshaws pulled by coolies at a trot, to servicemen carrying our own luggage! A similar situation to which today's passengers on luxury cruises experience at the end of the cruise! That is, back to reality!

Back on the train, after those ten days of opulence, the huge social inequalities of the Indian society, the beggars, and the squalor overwhelmed me. I felt uneasy sitting in the relative luxury of a comfortable clean seat knowing that above my head, on the roof, the wretched quotidian masses were roasting in the fierce Indian sun while hanging on for dear life. But then, I thought, if ninety years of the British Raj did not change these conditions, nothing will! So I relaxed and mentally prepared myself to enjoyed the long ride back to my ship!

To our consternation, in early March 1942, there was a change of command. A new skipper, Captain Petropoulos, arrived in Bombay to take over from Captain Matesis. Petropoulos was a martinet, with an unpleasant aura of arrogance. A distant short-temperate commander, economical with words of encouragement or praise, who did not miss an opportunity, in matters of inferior moment, to harass and demean all under him. His cold personality and his tendency to drive his men hard made him widely disliked by his officers; and he never missed an opportunity to bully those around him. He was often sullen and ill-tempered for hours. He was as disliked by sailors and officers as Matesis was liked and admired. And before long, the rumors circulating were that he was either crazy, beyond redemption, or a petty tyrant and a liar.

A rather tall and skinny man with a heavily wrinkled face, thus the moniker "Xaradras," (canyons) [8] a not-so-complementary moniker for a senior officer, but in short time, it was replaced with the treasonous nickname "Red Captain," which stayed with him for the rest of his life for his involvement in the naval Mutiny in Egypt!

He had the reputation of a smart and capable Staff Officer, up to his limitations. And although he had a good war record during the 1940-41 period, unfortunately, he also had many negative personality traits. Cold, aloof, and with a quick and cutting wit sharp enough to smart. As a result, it did not take long before his perverse personality and his penchant for always finding something wrong to berate subordinates created a toxic and hostile work environment. Consequently, soon after his arrival, the famously congenial camaraderie that marked AVEROF's wardroom disappeared—lest one wanted to be subjected to Petropoulos' shrill voice upbraiding someone for some minor infraction.

The disdain for the man was palpable. There was no doubt as to how matters stood between him and his officers. He had rubbed a lot of people the wrong way, and we were not alone in our ill-sentiments. Even the land-based crews attached to AVEROF despised him and feared his wrath. Hence, it did not take long before the unspoken wish of all those on board was that during a dark and stormy night Petropoulos would be met with a "tragic accident!" But fortunately, nobody had to act on such a malevolent wish, fate intervened.

By mid-May, a situation reminiscent of Captain Bligh and his First Officer Christian Fletcher aboard the Bounty developed. After Petropoulos publicly manhandled a sailor, the senior officers kind of mutinied. They ordered him off the ship and confined him in a hotel—lucky him we were not in the middle of the Indian Ocean to be thrown in his captain's gig and set adrift with food and water enough for a couple of days, as Christian did to Bligh!

Fortunately, the senior officers very wisely, I may add, kept the cadets out of AVEROF's internal problems. And although we were aware of what was happening, we continued our studies normally, especially now that AVEROF was not going out on escort missions, being aware of the circulating rumors that the captain was suffering from some kind of mental imbalance.

As the news of the events on AVEROF reached the high command in Egypt, Captain Antonopoulos was dispatched to investigate. Shortly after, trials and severe penalties were meted out, "on the guilty and not guilty." Several Staff Officers were retired and others imprisoned. Even the ship's doctor did not escape punishment. Meanwhile, the cause of it all, Petropoulos, like Bligh, was court-martialed and given a slap on the wrist for punishment. I believe he received some kind of reprimand and sent back to active service. However, two years later he got his just deserts. He was sentenced to twenty years in prison and discharged for his active involvement in "The mutiny in the Middle East." And ever after he was known in the Fleet as "The Red Captain."

The "resort," open to other Allies, as well, was in the vicinity of several "transit" camps, including a hospital for British troops destined for operations in the India-Burma-China theater of war and for those returning from Burma and other parts of India on their way home.

Naturally, the "resort" was off limits to those in the camps. And as I later found out, although the "resort" resembled the camps, the difference was like night and day. Consequently, my fond memories of Deolali were (and still are) in stark contrast with the memories of those who passed through the camps. For the British troops who spent time there, Deolali had a rather negative reputation. It was known as a place of boredom, illness, and severe mental problems. As a matter of fact, for the British, "gone Deolali" meant someone had gone crazy or was mentally disturbed.

My group's Deolali "dream vacation" began when we were dropped at the Bombay train station, a magnificent Victorian building, and one of the indisputable benefits of British colonialism. We arrived at the time when countless dabbawalas (food delivery boys), on foot or riding bicycles, were fanning out in a chaotic fashion to deliver tiffing boxes of homemade lunches. We entered a cavernous hall packed with people yelling and screaming and hands waving in the air. Thus, from the orderly life aboard the ship we found ourselves in the midst of a noisy and frenetic place; trains, people, cows, soldiers, flies, magicians, more flies, beggars, carts, more cows ... and hordes of semi-clad barefooted street urchins swarming us, arms extended and palms up, begging: “Backsheesh, Sahib”—and trying to hire themselves as porters. Thus, for half a rupee(?), not only did I have my bag carried but from being a young officer, a mere Ensign of no importance, I was instantly elevated to ... “Sahib!”

In anticipation of the four-hour trip and not knowing what accommodations were on the train, we thought it would be prudent to take care of our physical needs before boarding; what a horrible mistake! Half of the group stayed put keeping an eye on our luggage—that is, on our newly hired porters from absconding with them—while about five of us headed for the "restroom." Well, that "restroom" defied description. Besides the horrid stench aggravated by the humid summer-like Indian weather, the flies, and the wet floor, the facility was primitive and beyond disgusting. A ten-meter-long and half-meter-wide concrete ditch, separated into stalls by one-meter-tall walls without doors, filled with a stew of feces and urine—men and women squatting over it, disturbing the flies feasting on that filth. And no water in sight for flushing it or for washing hands.

With a quick about-face, wildly flailing our arms in the air to ward off flies buzzing about with their hairy legs dipped in feces, we exited the room before being asphyxiated by the noxious odors and joined our party, trying to expunge that revolting image from our brain.

"Backsheesh" accounts settled, me and the other AVEROF newly anointed "Sahibs," following our "porters," pushed, shoved, and squeezed our way through a churning sea of people, animals, baggage, and piles of rubbish to get to our train. The train was a sight to behold! We got into it, whereas the hordes of "untouchables" and their possessions were on it—crammed on the hot steel roofs or hanging from the rust-pocked handrails—and kids hanging from the windows begging for money. if I had not seen them when I boarded the train, I would have thought that they were on stilts.

Our coach was full but not crowded. Just Indian and Allied officers and upper-caste civilians with their servants taking care of the children, most of them resembling miniature Maharajas in corpulence and attire; in stark contrast to the kids hanging outside the windows. Well, "c'est la vie!"

We all had comfortable seats, albeit the wooden-bench variety. Of course, luggage filled the aisle in the middle of the car between the two rows of benches which made it quite a challenging obstacle race to visit the restroom. That is, a 4'x4' foot enclosure at the end of the car with just a hole in the floor, with a clear view of the railroad ties speeding in the opposite direction below your feet. And God only knows what was going on in the second class coaches or on the roofs. The air inside the car, despite the open windows, was hot and stifling, a mixture of sweat, curry, and rotten food. Although it improved considerably once we got going.

With a shriek blow of the train's whistle, the clank of the couplings, and a jolt our Deolali trip began. Instinctively, I turned my head to take a last look through the window, while waving away a fly from landing on my hair, when I saw a terrifying scene unfolding: A tsunami of desperate humanity rushing toward the train. Men, women, and children running alongside the tracks trying to get a hold of the ever faster-moving train. Some made it, some fell off, and the rest gave up the chase huffing and puffing like cheetahs outrun by the prey. Were there any casualties? Who knows! And worst yet, it was apparent that nobody cared!

We moved at a good clip being serenaded by the clack-clack, clickety-clack of the wheels while the scenery outside was constantly changing with every sharp turn; from lush green valley to semi-desert, from flat terrain to horrifying drops down to rugged canyons, and from horrendous precipices to deep jungle gorges. To this day I wonder how the "outsiders," the people on the roofs and those hanging outside, using unimaginable nook and crannies for a foothold, did not fly off the train or did not fry being exposed to the scorching Indian sun!

After about four hours we arrived in Deolali. Although the train station was considerably smaller than the one in Bombay, the scenery was equally, if not more, chaotic. Even before the train came to a complete stop, people were clambering down from the roofs. Animals and packages were thrown, pushed, or dropped to the ground. The privileged kids in our coach were guided tenderly by their nannies and the infants were handed over people's heads and passed carefully to a waiting servant—whereas the children of the plebeian masses were tossed from the roofs to someone's extended arms on the platform.

However, unlike our experience boarding the train in Bombay where we had to push our way through a sea of people and animals, here, as guests of the (British) Crown, we found ourselves under the "protection" of a British-Indian detachment waiting for us. It acted like "Moses," parting the sea of people and animals, leading us to "the promised land"--a somewhat comfortable looking military vehicle for the short ride to the resort.

On the way, we were treated to some more exotic adventures, as far as we were concerned, but a huge nuisance for the driver who had to deal with them regularly. As we rounded a curve, the bus came to an abrupt stop, while the billowing dust enveloped us. Fanning ourselves and squinting at the plume of dust we saw in the shimmering distance a half-necked fakir brandishing a rather lethal-looking stick coming toward us. He began banging on the sides of the bus with his stick and demanding, you guessed it, “baksheesh!”

But having already been anointed "Sahibs" at the Bombay train station, and being in the relative safety of “His Majesty’s” vehicle, and, more importantly, still carrying our sidearms, none of us was sympathetic towards a wild self-appointed "toll collector" demanding baksheesh to let us pass. So, he got nothing but scornful looks and snide comments. And with a few more gratuitous bangs on the side of the bus with his stick, accompanied with several less than holy hand-gestures and loud curses, he retreated to the shade under a tree assuming the lotus position, legs crossed and arms folded, waiting for the next passing conveyance to attack.

Relieved and mostly amused by the incident we were ready to go. But the bus did not move. While we were preoccupied with the fakir another "holy entity" blocked our way; a Brahman bull! He had plopped himself in the middle of the road and despite our irreverent and “politically incorrect” yelling and shouting, he would not budge. He kept staring at us with that characteristic bovine indifference regardless of our lack of reverence. Eventually, we had to drive off the road around him. However, unlike the fakir, he did not shout or gesticulate at us. He did not seem to be bothered at all—he looked impressive in his state of absolute divine serenity!

With the fakir and the bull being the hot topic of conversation, and the butt of some irreverent jokes, before long, we were let out at a "dak bungalow," a typical Indian Government structure. In essence, it was a big hall that served as the "reception" facility, whose center was occupied by a wooden life-size sculptured figure of some rather grotesque looking deity. And there was where our dream vacation really began.

Deolali was an idyllic place in every aspect, partly Indian and partly English, with abundance of greenery and spectacular scenic vistas of forested hills. The weather was hot and sultry, the locale rural, and the mosquitoes ... big as elephants! Of course, that's nothing if you consider the ever-present danger of crossing paths with a cobra, a scorpion, or being dive-bombed by a hawk to steal your lunch—and gargantuan vermin was a common sight.

Luckily, in the residence hall and at the club, nets, huge electric ceiling- and pankah-fans, complete with pankah boys in turban thrashing away, made the heat comfortable, if not bearable, and kept the mosquitoes at bay. The hawks, when they were not stealing lunches, were taking care of the scorpions and the vermin—I never had my lunch stolen by a hawk, because I never ate outdoors, as some British did. And at night we were lulled to sleep counting the mosquito kamikaze-attacks on our mosquito bed nets.

Cobras, however, was a different story! Since they had mystical powers over the natives, pestering or killing one would have been the modern-day equivalent of an "international incident of foreign aggression!" Fortunately, my encounter with a cobra was from a safe distance, in a crowded street in Bombay! It cost me a couple of coins to see one coming up from a snake charmer's basket—a mesmerizing and rather repulsive spectacle!

Notwithstanding the heat, the mosquitoes, and the cobras, my stay in Deolali was pleasant and very relaxing; hobnobbing with British "servants of the Empire"—R.N. officers, H.M.'s Highlanders, ANZACs (Australian and New Zealanders), South Africans, Rhodesians and others—in the opulence of the Officers' Lounge being treated like royalty, where the conversation revolved more about Polo, Golf, and Tennis rather than Rommel, Auchinleck, or El Alamein! In short, the overall ambiance was something new for us, a combination of the excesses of British aristocracy and the pleasures of colonial India. There is where I saw the splendor of the British Empire in all its "glory."

In addition to the Sepoys—Indian natives serving in the British army—there was an army of turbaned servants; valets, barbers, porters, shoe-shine boys, and cloth-washing women. They were everywhere, in the sleeping quarters, the Club House, the Billiards Rooms, the gardens, and at the rarely used, because of the heat, Tennis, Rugby, and Racket courts, ready to render their services.

Some orderlies wore a small sword, slung short from their waste. It reminded me of my "Cadet's Dagger" the Turkish officer stole from me when we landed in Turkey on our way to Alexandria.

Besides the plentiful food and the cocktail mini-parties at the club, the cool hours of the day were spent on all kinds of leisurely activities such as falconry! Well, a modified form of falconry! That is, teasing the hawks by throwing in the air bones or pieces of meat from the dumpster and watching them dive to catch them mid-air. Of course, the elephant vs. camel races were one of the favorites. They did not require any physical exertion on our part except having a strong stomach to down those cool but spicy beverages freely served by roving servants in our private, cordoned off and sun protected section of the field. Tennis, of course, was the "un-required" but "obligatory" activity for proclaiming our European elan and sophistication. However, after a couple of volleys, we would get drenched with sweat and rush back to our living quarters for a refreshing shower. And, at least once during our stay—and that was enough—we had to make the arduous trek to the "rock," in the hottest time of the day. The "rock" was a massive rock, in the periphery of the resort, heated by the sun to the point where we could fry eggs on it, for the day's ritualistic tiffin (lunch)!

Another pastime was the escorted visits to the town. It was a diversion from the dreamy life at the resort. The town ambiance was a scaled-down version of Bombay; the good sections and the bad sections, the roaming cows, and the feasting flies on the cow dung; the red light district offering a cornucopia of forbidden pleasures, and the upper caste section of the town; the rich store owners and the begging children; the usual street merchants and the Bazaar. The Bazaar was no different than other bazaars but it seemed to have many more produce stands with delicious looking and hard to resist fresh fruits. Unfortunately, though, once we were informed that some (most?) of the fruit was grown in sewage farms their appeal instantly disappeared.

Incidentally, the same happened when our guide took us to the red-light district. The merchandise looked as delicious and as juicy as the fruit in the bazaar; incredibly beautiful young women with exquisite exotic features, some hardly over the age of consent! But looking at the surroundings and the slime bubbling up from the open sewers in the middle of the street made any youthful urges we may have had to be instantly killed—perhaps a blessing in disguise. It also killed the real or mostly imaginary tails of conquests of fetching young ladies span by men following the return from the town visits.

On a happier note, strolling down the street we came across a loud, sleigh-of-hand magician entertaining the crowd with levitation and a trick involving a coin and a chicken. We stood off to the side trying not to distract the crowd with our presence, and with hands in our pockets to discourage any pickpockets working independently or with the magician, and trying to look nonchalantly at the magician's antics.