Adrias beached at Gumusluk—all that remained from a once-mighty ship.

Adrias beached at Gumusluk—all that remained from a once-mighty ship.

"They that go down to the sea in ships ... So He bringeth them unto their desired haven."

Psalm 107, The Sailor's Psalm.

Half-drowned, filthy, torn, exhausted, and with tearful thanks to God we arrived in Gumusluk, a tiny little village with a long jetty and a narrow inlet, around 1:00 a.m. on October 23, 1943.

When "rosy-fingered Dawn," quoting Homer, appeared she revealed a panorama of wreckage and carnage. ADRIAS, a beautiful ship a day earlier, was now an apocalyptic ruin of violence, misery, and horror beyond imagining—a frightful scene, corpses everywhere. The ship was a pulverized cauldron of mangled steel and flesh. Men lay where they had fallen, bloated and contorted into grotesque poses, on the deck, the gun encasements, and the passageways. Most of the wounded were not moving and some writhing in pain from wounds, wounds from which some did not recover. Death was all over the place.

ADRIAS was beached on a 7-degree starboard list and where the bows used to be now was a heap of crimped amorphous metal. Dead and wounded strewn everywhere and the stench of blood and decomposing bodies was in the air. The forward turret that was now precariously resting on the top of what used to be the bridge had become a death trap for most of its crew. It was then that I truly realized the magnitude and the horrors of the explosion. Without a doubt, Adrias was the most smashed-up ship that anyone has ever seen come in from the sea. A disaster of epic proportions.

As soon as the ship was beached and secured from capsizing I left my station and ran with my crew toward the front responding to captain Toumbas' directive: "boys*, let's save them [the wounded] "—which was more of a cajoling request than an order, although no order or cajoling was needed.

I vividly remember my horror, making my way toward the front, among the competing yells and commands, slipping on blood and stepping on a severed hand. Ever since, whenever I step on a soft surface like a carpet, I am reminded of that.

On my way to the front, through the cacophony of moans and shouts, broken glass and twisted beams, I saw commander Toumbas coming from the opposite direction, visibly in pain from the wounds he had suffered but very much in control. I stepped aside to let him pass but he stopped in front of me. He looked at me in the eyes for a few seconds and in a low but steady voice said: "Themelis is trapped in the turret."

I felt the deck open under me! The statement hung in a silence that his eyes expected me to fill, and a chill of absolute fear for my friend's life ran through my spine. I don't remember whether I said "yes, sir," "aye, aye, sir," or asked for permission to leave. I turned and rushed forward passing bent metal, dripping oil, and horribly mangled bodies stained with dark blood and mentally preparing myself for what I would find in the turret. The passage grew more gloomy as me and a couple of sailors climbed up, ladder after ladder, high toward the bridge, my crew right on my heels, with the unmistakable odor of death offending our nostrils. And as we went up the air smelled fresher.

When I got to what used to be the bridge, I could not believe my eyes; utter devastation—a horrendous sight, horrible and hellish. Charts, signal flags, sextants, and binoculars were strewn all over. The compass was torn away and the binnacle was ripped off its fastenings. And just above me the turret was precariously resting with its guns pointing backward toward the sky, and lying on the floor among broken glass and splintered wood were four-inch shells. That is, shells two and a half feet long and four inches in diameter, some of them bent to right angles—that gives you an idea of the power of the explosion. And if that was not enough of a shock, among the debris I see Androulakis, my old childhood Cretan friend, dead on the floor with a horrific gaping wound in his throat and his Cretan buddy, E. Kokkolakis, crying next to him.

I was shocked and deeply saddened, but I knew there was nothing I could do for him now. With a heavy heart, I waved to my men to follow me. We climbed on what used to be the forward turret and found my friend, Kostas Themelis, and his crew trapped in the crumpled metal. It took us hours and a superhuman effort to free him and his men, the ones who were still alive. They were all in bad shape. Themelis' both knees were broken. He could not move. And all this time he suffered in silence, not a single moan escaped his lips, despite the unbearable pain he must have felt.

Once freed, I got hold of him and personally carried him [1] in my arms to the makeshift "hospital" Dr. Kapodistrias had made out of the non-commissioned officers' lounge.

The "hospital" was a house of horrors. In fact, the sight was shocking, beyond horrific, and grotesque. The outside racket of hollering, repairs, and orders was drowned out by a low-level wail of amorphous anguish, and the smells of iodine and cauterization hung in a pall. I had seen wounds before, seen men gutted by shrapnel, cut in half by machine gun, seen heads split open by a bullet. But nothing could have prepared me for what I saw. Severely wounded, maimed, and dying men, some still dazed and befouled with excrement and oil, lay supine on tables or sitting slumped in anguish on the floor or against the bulkhead, awash with gall and gore. At the corner, a sailor lying flat on the floor, racked by fever, thinking that the ambient voices were the ghosts of lost mates, was calling their names like a macabre requiem for the fallen. And those who could stand were at the back wall in various bandages and slings, while cries of pain were coming out of those under treatment.

As soon as I entrusted Themelis into Dr. Kapodistrias' skilled hands, I felt a clawed hand groping for my sidearm. Instinctively, I turned and grabbed the intrusive hand by the wrist. Eyes of fading life belonging to a sailor's face whiter than death, whose name I don't remember, gazed up at me begging for deliverance from the pain of a horrendous head wound oozing blood all over his face.

As I was gently returning his hand to his side, he whispered to me: “Ensign, sir, please kill me.” I was stunned. I'll never forget the expression on that man's bloodied face and that he still had the presence of mind to call me "Ensign, sir! " I stayed by his side and began to whisper comforting words, which I doubted he even heard, as I used a cotton pad to wipe away the blood from dripping in his mouth. His eyes were open and fluttering with that characteristic lifeless sheen of his eyeballs and gasping for breath trying to hold on to life. Dr. Kapodistrias' assistant, attending to the wounds of another man nearby, looked at me and shook his head to let me know that "my patient's" situation was hopeless. I nodded back in silent understanding and continued wiping the blood until I was relieved by a medic. Later on, I learned that the sailor had died. To this day I shiver thinking about his request to kill him. I could not even begin to imagine of doing such a thing.

Shortly after, the engine Quartermaster G. Papafrantzeskos walked in holding with his right hand his almost severed left arm. Dr. Kapodistrias had to amputate his arm—with a common pair of scissors and without anesthesia! Papafrantzeskos’s reply “what is a hand for our country,” to Toumbas, when the latter came to visit him in the sickbay, has become a legend in our Navy. Incidentally, Papafrantzescos' requested to stay in active service, and although he had lost one arm, his request was granted.

As I stepped outside the "hospital" to the open deck, I barely could contain myself from crying seeing those men lying there severely wounded, maimed or dying. I turned to take a last look at the nightmare behind me and the thought crossed my mind that if ever there was a time to doubt the existence of a benevolent God, it must be this one. But then, recalling my mother's advice, I quickly perished the though, I always knew He existed.

Themelis eventually recovered, but his wounds in effect put an end to his active naval career. He was placed on the reserves and passed away in 1984 with the rank of Commander.

The ship’s doctor, the indefatigable Sub-Lieutenant Kapodistrias was outstanding. With hardly any sleep since the explosion, he radiated a steadfast composure even though his sickbay was demolished—left without tools or pharmaceuticals. He cared for the wounded with compassion and sensitivity with whatever drugs he could scrounge from the emergency First Aid kits. He had converted the non-commissioned officers’ lounge in the stern, into an operating room without having the basic equipment, the luxury of an anesthesiologist, or unlimited amounts of morphine. With skilled hands that even veteran surgeons would envy, he was plucking out metal fragments from deep wounds, bandaging, and amputating limbs. He remained tireless and cool-headed using the shaving cologne he had scrounged from the non-commissioned officers quarters as antiseptic. He saved many lives.

Sadly, several of those trapped in the wreckage could not be freed without heavy-duty equipment capable of bending metal. The only thing we could do for them until the equipment arrived was to give them shots of morphine to ease their pain. So, for days, we were subjected to the ghastly view of a motionless hand here or a foot there protruding from the wreckage. And if that was not enough, due to the summer-like weather, the trapped bodies had already started to decompose making their removal, if nothing else, a public health necessity. The only way this could be done was by cutting the corpses to pieces. Naturally, none of us wanted to do such a thing. Thankfully, our bold Exec, Lt. Haritopoulos, found a tolerable solution—he hired locals for that macabre job.

So, for days a strong odor of burnt metal and rotting flesh hung in the air. But, there were "miracles" among the carnage, as well. A sailor who had been blown to the sea when we hit the mine was swept back on board by a big wave, suffering only a minor wound on his nose. Another was blown on the torpedo tubes and survived, although he broke his back. And let us not forget our sailor A. Savvakis and captain "D" showing up from Hurworth's dead and missing! [2]

Of course, besides me and my crew, there were many others whose acts of heroism and self-sacrifice, I am afraid, will never be known, even though Admiral Toumbas has chronicled most of them in detail in his book [3].

For the lucky ones who were not wounded the emotional toll was high. It is hard to hear about friends being wounded or lost in another ship, but it is an entirely different story seeing men, in your own ship, with whom until a while ago you were talking to and laughing with being maimed, disfigured, or dead.

Sadly, the mine's ghastly toll in lives and injuries was about 30% of Adrias' complement: Twenty one dead and thirty wounded. Moreover, daybreak brought another slew of problems to be addressed: Taking care and transferring the wounded, burial of the dead, survival of the crew, legalities, British support, and last but not least, the repair of our ship.

Which reminds me of a comment I had heard long time ago, I can not recall from whom, perhaps in the Academy, that "glory and honor (Δοξα και Τιμη) are won if battle happened over there, but when one is personally involved, it's only terror, confusion, and sorrow."

----------- . ---------------

Psalm 107, The Sailor's Psalm.

Half-drowned, filthy, torn, exhausted, and with tearful thanks to God we arrived in Gumusluk, a tiny little village with a long jetty and a narrow inlet, around 1:00 a.m. on October 23, 1943.

When "rosy-fingered Dawn," quoting Homer, appeared she revealed a panorama of wreckage and carnage. ADRIAS, a beautiful ship a day earlier, was now an apocalyptic ruin of violence, misery, and horror beyond imagining—a frightful scene, corpses everywhere. The ship was a pulverized cauldron of mangled steel and flesh. Men lay where they had fallen, bloated and contorted into grotesque poses, on the deck, the gun encasements, and the passageways. Most of the wounded were not moving and some writhing in pain from wounds, wounds from which some did not recover. Death was all over the place.

ADRIAS was beached on a 7-degree starboard list and where the bows used to be now was a heap of crimped amorphous metal. Dead and wounded strewn everywhere and the stench of blood and decomposing bodies was in the air. The forward turret that was now precariously resting on the top of what used to be the bridge had become a death trap for most of its crew. It was then that I truly realized the magnitude and the horrors of the explosion. Without a doubt, Adrias was the most smashed-up ship that anyone has ever seen come in from the sea. A disaster of epic proportions.

As soon as the ship was beached and secured from capsizing I left my station and ran with my crew toward the front responding to captain Toumbas' directive: "boys*, let's save them [the wounded] "—which was more of a cajoling request than an order, although no order or cajoling was needed.

I vividly remember my horror, making my way toward the front, among the competing yells and commands, slipping on blood and stepping on a severed hand. Ever since, whenever I step on a soft surface like a carpet, I am reminded of that.

On my way to the front, through the cacophony of moans and shouts, broken glass and twisted beams, I saw commander Toumbas coming from the opposite direction, visibly in pain from the wounds he had suffered but very much in control. I stepped aside to let him pass but he stopped in front of me. He looked at me in the eyes for a few seconds and in a low but steady voice said: "Themelis is trapped in the turret."

I felt the deck open under me! The statement hung in a silence that his eyes expected me to fill, and a chill of absolute fear for my friend's life ran through my spine. I don't remember whether I said "yes, sir," "aye, aye, sir," or asked for permission to leave. I turned and rushed forward passing bent metal, dripping oil, and horribly mangled bodies stained with dark blood and mentally preparing myself for what I would find in the turret. The passage grew more gloomy as me and a couple of sailors climbed up, ladder after ladder, high toward the bridge, my crew right on my heels, with the unmistakable odor of death offending our nostrils. And as we went up the air smelled fresher.

When I got to what used to be the bridge, I could not believe my eyes; utter devastation—a horrendous sight, horrible and hellish. Charts, signal flags, sextants, and binoculars were strewn all over. The compass was torn away and the binnacle was ripped off its fastenings. And just above me the turret was precariously resting with its guns pointing backward toward the sky, and lying on the floor among broken glass and splintered wood were four-inch shells. That is, shells two and a half feet long and four inches in diameter, some of them bent to right angles—that gives you an idea of the power of the explosion. And if that was not enough of a shock, among the debris I see Androulakis, my old childhood Cretan friend, dead on the floor with a horrific gaping wound in his throat and his Cretan buddy, E. Kokkolakis, crying next to him.

I was shocked and deeply saddened, but I knew there was nothing I could do for him now. With a heavy heart, I waved to my men to follow me. We climbed on what used to be the forward turret and found my friend, Kostas Themelis, and his crew trapped in the crumpled metal. It took us hours and a superhuman effort to free him and his men, the ones who were still alive. They were all in bad shape. Themelis' both knees were broken. He could not move. And all this time he suffered in silence, not a single moan escaped his lips, despite the unbearable pain he must have felt.

Once freed, I got hold of him and personally carried him [1] in my arms to the makeshift "hospital" Dr. Kapodistrias had made out of the non-commissioned officers' lounge.

The "hospital" was a house of horrors. In fact, the sight was shocking, beyond horrific, and grotesque. The outside racket of hollering, repairs, and orders was drowned out by a low-level wail of amorphous anguish, and the smells of iodine and cauterization hung in a pall. I had seen wounds before, seen men gutted by shrapnel, cut in half by machine gun, seen heads split open by a bullet. But nothing could have prepared me for what I saw. Severely wounded, maimed, and dying men, some still dazed and befouled with excrement and oil, lay supine on tables or sitting slumped in anguish on the floor or against the bulkhead, awash with gall and gore. At the corner, a sailor lying flat on the floor, racked by fever, thinking that the ambient voices were the ghosts of lost mates, was calling their names like a macabre requiem for the fallen. And those who could stand were at the back wall in various bandages and slings, while cries of pain were coming out of those under treatment.

As soon as I entrusted Themelis into Dr. Kapodistrias' skilled hands, I felt a clawed hand groping for my sidearm. Instinctively, I turned and grabbed the intrusive hand by the wrist. Eyes of fading life belonging to a sailor's face whiter than death, whose name I don't remember, gazed up at me begging for deliverance from the pain of a horrendous head wound oozing blood all over his face.

As I was gently returning his hand to his side, he whispered to me: “Ensign, sir, please kill me.” I was stunned. I'll never forget the expression on that man's bloodied face and that he still had the presence of mind to call me "Ensign, sir! " I stayed by his side and began to whisper comforting words, which I doubted he even heard, as I used a cotton pad to wipe away the blood from dripping in his mouth. His eyes were open and fluttering with that characteristic lifeless sheen of his eyeballs and gasping for breath trying to hold on to life. Dr. Kapodistrias' assistant, attending to the wounds of another man nearby, looked at me and shook his head to let me know that "my patient's" situation was hopeless. I nodded back in silent understanding and continued wiping the blood until I was relieved by a medic. Later on, I learned that the sailor had died. To this day I shiver thinking about his request to kill him. I could not even begin to imagine of doing such a thing.

Shortly after, the engine Quartermaster G. Papafrantzeskos walked in holding with his right hand his almost severed left arm. Dr. Kapodistrias had to amputate his arm—with a common pair of scissors and without anesthesia! Papafrantzeskos’s reply “what is a hand for our country,” to Toumbas, when the latter came to visit him in the sickbay, has become a legend in our Navy. Incidentally, Papafrantzescos' requested to stay in active service, and although he had lost one arm, his request was granted.

As I stepped outside the "hospital" to the open deck, I barely could contain myself from crying seeing those men lying there severely wounded, maimed or dying. I turned to take a last look at the nightmare behind me and the thought crossed my mind that if ever there was a time to doubt the existence of a benevolent God, it must be this one. But then, recalling my mother's advice, I quickly perished the though, I always knew He existed.

Themelis eventually recovered, but his wounds in effect put an end to his active naval career. He was placed on the reserves and passed away in 1984 with the rank of Commander.

The ship’s doctor, the indefatigable Sub-Lieutenant Kapodistrias was outstanding. With hardly any sleep since the explosion, he radiated a steadfast composure even though his sickbay was demolished—left without tools or pharmaceuticals. He cared for the wounded with compassion and sensitivity with whatever drugs he could scrounge from the emergency First Aid kits. He had converted the non-commissioned officers’ lounge in the stern, into an operating room without having the basic equipment, the luxury of an anesthesiologist, or unlimited amounts of morphine. With skilled hands that even veteran surgeons would envy, he was plucking out metal fragments from deep wounds, bandaging, and amputating limbs. He remained tireless and cool-headed using the shaving cologne he had scrounged from the non-commissioned officers quarters as antiseptic. He saved many lives.

Sadly, several of those trapped in the wreckage could not be freed without heavy-duty equipment capable of bending metal. The only thing we could do for them until the equipment arrived was to give them shots of morphine to ease their pain. So, for days, we were subjected to the ghastly view of a motionless hand here or a foot there protruding from the wreckage. And if that was not enough, due to the summer-like weather, the trapped bodies had already started to decompose making their removal, if nothing else, a public health necessity. The only way this could be done was by cutting the corpses to pieces. Naturally, none of us wanted to do such a thing. Thankfully, our bold Exec, Lt. Haritopoulos, found a tolerable solution—he hired locals for that macabre job.

So, for days a strong odor of burnt metal and rotting flesh hung in the air. But, there were "miracles" among the carnage, as well. A sailor who had been blown to the sea when we hit the mine was swept back on board by a big wave, suffering only a minor wound on his nose. Another was blown on the torpedo tubes and survived, although he broke his back. And let us not forget our sailor A. Savvakis and captain "D" showing up from Hurworth's dead and missing! [2]

Of course, besides me and my crew, there were many others whose acts of heroism and self-sacrifice, I am afraid, will never be known, even though Admiral Toumbas has chronicled most of them in detail in his book [3].

For the lucky ones who were not wounded the emotional toll was high. It is hard to hear about friends being wounded or lost in another ship, but it is an entirely different story seeing men, in your own ship, with whom until a while ago you were talking to and laughing with being maimed, disfigured, or dead.

Sadly, the mine's ghastly toll in lives and injuries was about 30% of Adrias' complement: Twenty one dead and thirty wounded. Moreover, daybreak brought another slew of problems to be addressed: Taking care and transferring the wounded, burial of the dead, survival of the crew, legalities, British support, and last but not least, the repair of our ship.

Which reminds me of a comment I had heard long time ago, I can not recall from whom, perhaps in the Academy, that "glory and honor (Δοξα και Τιμη) are won if battle happened over there, but when one is personally involved, it's only terror, confusion, and sorrow."

----------- . ---------------

K. Themelis

K. Themelis

Lieutenant Themelis (picture courtesy of his son, Tony Themelis)

Konstantinos Themelis, one of the heroes of the ADRIAS epic story. Although severely wounded he eventually recovered, but his wounds put an end to his active naval career. He was placed on the reserves and served in that capacity for many years. He passed away in 1984 with the rank of Commander.

Christos and Konstantinos remained friends. Years later, according to his son, Tony, every time the Themelis family would visit Greece, his father would spend a whole day with Christos.

Konstantinos Themelis, one of the heroes of the ADRIAS epic story. Although severely wounded he eventually recovered, but his wounds put an end to his active naval career. He was placed on the reserves and served in that capacity for many years. He passed away in 1984 with the rank of Commander.

Christos and Konstantinos remained friends. Years later, according to his son, Tony, every time the Themelis family would visit Greece, his father would spend a whole day with Christos.

[Author’s note: I never had the honor of meeting Admiral Toumbas in person. However, because of my cousins, his name and illustrious career, in and out of the uniform, were well known in the family circles. Moreover, anyone who has read the Admiral’s book, EXTHROS EN OPSI, should not be surprised for his sensitivity, perfect choice of words, and his insightful historical presentation of Greece's naval involvement during WW II—it's a masterpiece].

Cousin Christos gave me a copy of it as souvenir of our visit to the Nautical Museum. I read it for first time during my 10-hour layover at the Berlin airport waiting for my return flight to San Francisco.

----------------------------- . -----------------------------------

Cousin Christos gave me a copy of it as souvenir of our visit to the Nautical Museum. I read it for first time during my 10-hour layover at the Berlin airport waiting for my return flight to San Francisco.

----------------------------- . -----------------------------------

Gumusluk, men returning from Liberty

Gumusluk, men returning from Liberty

Gumusluk was a small fishing village, as you can see from the picture. It was inhabited by Turko-Cretans who spoke Greek fluently. Its center of "social life" was Ali's coffeehouse [Kafeneion]. Also, there was a small gendarmerie detachment and a certain Hasan Bey, who in reality was a Greek army lieutenant, in the reserves, living there for some time. His real name was N. Myristis, a wireless operator in the [British] "hush-hush business," an Intelligence Service agent in contact with Cairo. Needless to say that his services were of paramount importance since Adrias' radio and all her other communications equipment was destroyed.

Early in the morning, we transferred the wounded to Ali's café. Meanwhile, a British consular representative from Smyrna arrive. No sooner than the consular rep had arrived, we were visited by a German observation plane, circling the bay watching us. Because of its subsequent regularity of its visit, it became a pastime for us watching the plane watching us!

Around noon, a Turkish Army officer with an entourage of a few armed soldiers showed up. That did not bode well for our future. Toumbas was immediately notified and came ashore to meet him. The Turkish officer proceeded to inform Toumbas that if we did not depart within twenty-four hours he would seize Adrias. Toumbas stood his ground. He smirked and nodded toward "my turret."

"Pekiyi, effendi," the Turkish officer said, slipping his voice to a higher register, and took his leave. And that was the end of it.

As we were watching them go away we could hardly restrain our sense of pride, relief, and enthusiasm. However, Toumbas, who was always on the lookout for potential dangers, trying not to squash our enthusiasm, turned toward me and in a calm and self-deprecating tone of voice said: "Papasifaki, be sure your [turret's] guns are ready [for action]."

I immediately knew what he meant. "Aye aye, sir," I perked up with glee, backing out of the group and with a smart salute I made a right about-face and ran toward the service launch to get to my turret.

However, as much as I want to believe that it was my turret's "ominous looking" guns and Toumba's bravado that convinced the Turks not to bother us during the next thirty-nine days we stayed there in clear violation of International Treaties, in reality, this favorable for us, or to be more precise for the British, stance of "Neutrality" had to do more with the fact that by then the scale of victory was tipping toward the Allies. Moreover, the Turks were well aware that Churchill was always looking for an excuse to avenge Gallipoli.

Evidently, the Turks very wisely thought that provoking the British Lion, even wounded, with its powerful American ally behind it, was not prudent—they left us alone, going about our business repairing ADRIAS, thus after the war Turkey becoming the "enfant gâté " of the NATO Alliance and its concomitant enormous American Military and financial aid.

With that problem solved, our attention was turned back to cleaning our ship from the oil that had covered everything and taking care of the wounded. In the early afternoon we transferred them into two caiques, we bade them "Godspeed," and under Dr. Kapodistrias' care they left for a hospital in Bodrum.

Early in the morning, we transferred the wounded to Ali's café. Meanwhile, a British consular representative from Smyrna arrive. No sooner than the consular rep had arrived, we were visited by a German observation plane, circling the bay watching us. Because of its subsequent regularity of its visit, it became a pastime for us watching the plane watching us!

Around noon, a Turkish Army officer with an entourage of a few armed soldiers showed up. That did not bode well for our future. Toumbas was immediately notified and came ashore to meet him. The Turkish officer proceeded to inform Toumbas that if we did not depart within twenty-four hours he would seize Adrias. Toumbas stood his ground. He smirked and nodded toward "my turret."

"Pekiyi, effendi," the Turkish officer said, slipping his voice to a higher register, and took his leave. And that was the end of it.

As we were watching them go away we could hardly restrain our sense of pride, relief, and enthusiasm. However, Toumbas, who was always on the lookout for potential dangers, trying not to squash our enthusiasm, turned toward me and in a calm and self-deprecating tone of voice said: "Papasifaki, be sure your [turret's] guns are ready [for action]."

I immediately knew what he meant. "Aye aye, sir," I perked up with glee, backing out of the group and with a smart salute I made a right about-face and ran toward the service launch to get to my turret.

However, as much as I want to believe that it was my turret's "ominous looking" guns and Toumba's bravado that convinced the Turks not to bother us during the next thirty-nine days we stayed there in clear violation of International Treaties, in reality, this favorable for us, or to be more precise for the British, stance of "Neutrality" had to do more with the fact that by then the scale of victory was tipping toward the Allies. Moreover, the Turks were well aware that Churchill was always looking for an excuse to avenge Gallipoli.

Evidently, the Turks very wisely thought that provoking the British Lion, even wounded, with its powerful American ally behind it, was not prudent—they left us alone, going about our business repairing ADRIAS, thus after the war Turkey becoming the "enfant gâté " of the NATO Alliance and its concomitant enormous American Military and financial aid.

With that problem solved, our attention was turned back to cleaning our ship from the oil that had covered everything and taking care of the wounded. In the early afternoon we transferred them into two caiques, we bade them "Godspeed," and under Dr. Kapodistrias' care they left for a hospital in Bodrum.

Gumusluk, Burial of Adrias' dead.

Gumusluk, Burial of Adrias' dead.

The next most urgent task was the burial of the dead. We rented a field on the shoreline nearby where ADRIAS was beached and we dug a huge grave to bury our fallen comrades, both Greek and British [9].

We wrapped each body in tarps and placed them one next to the other keeping track of each body's position for identification purposes upon re-burial [6] after the war.

We did the same for the British, Hurworth's dead, who were cast up on shore by the sea. We also wrapped, in one tarp, all the human parts that had fallen on our deck when Hurworth exploded.

We all lined up for the "call of the fallen "—all young men with dreams of victory and glory in their hearts. Toumbas called one-by-one the names of the dead and each time the Executive Officer replied "Absent, he fell for the Country" and then gave a brief eulogy.

I, being the youngest officer, was assigned to offer the funeral prayers. I had no idea what I should say and there were no books or literature left in the ship's library for such an occasion. Although grief-stricken, I said whatever I could think of at the moment, drawing inspiration from the Epitaph on the Cenotaph in Thermopylae, "ὦ ξεῖν', ἀγγέλλειν Λακεδαιμονίοις ὅτι τῇδε κείμεθα τοῖς κείνων ῥήμασι πειθόμενοι," (roughly translated, "Oh stranger, go tell the Spartans that here we lie, obedient to their orders.") But whatever I said it came from my heart. Incidentally, I am the one in black in the center of the picture kneeling and reciting the Lord's prayer.

After that simple but solemn and very emotional ceremony, we covered the grave with dirt and on top of it we poured a thick layer of concrete, and enclosed it with a barbed wire fence. But this did not put an end to our sorrow for our departed friends and comrades. I remember one night being the guard-duty officer when a sailor came to me shaking and told me that he could not stand guard at the same spot where Diopos Papamakarios was killed because he was afraid his ghost would appear!

We wrapped each body in tarps and placed them one next to the other keeping track of each body's position for identification purposes upon re-burial [6] after the war.

We did the same for the British, Hurworth's dead, who were cast up on shore by the sea. We also wrapped, in one tarp, all the human parts that had fallen on our deck when Hurworth exploded.

We all lined up for the "call of the fallen "—all young men with dreams of victory and glory in their hearts. Toumbas called one-by-one the names of the dead and each time the Executive Officer replied "Absent, he fell for the Country" and then gave a brief eulogy.

I, being the youngest officer, was assigned to offer the funeral prayers. I had no idea what I should say and there were no books or literature left in the ship's library for such an occasion. Although grief-stricken, I said whatever I could think of at the moment, drawing inspiration from the Epitaph on the Cenotaph in Thermopylae, "ὦ ξεῖν', ἀγγέλλειν Λακεδαιμονίοις ὅτι τῇδε κείμεθα τοῖς κείνων ῥήμασι πειθόμενοι," (roughly translated, "Oh stranger, go tell the Spartans that here we lie, obedient to their orders.") But whatever I said it came from my heart. Incidentally, I am the one in black in the center of the picture kneeling and reciting the Lord's prayer.

After that simple but solemn and very emotional ceremony, we covered the grave with dirt and on top of it we poured a thick layer of concrete, and enclosed it with a barbed wire fence. But this did not put an end to our sorrow for our departed friends and comrades. I remember one night being the guard-duty officer when a sailor came to me shaking and told me that he could not stand guard at the same spot where Diopos Papamakarios was killed because he was afraid his ghost would appear!

Adrias' Guard Detachment

Adrias' Guard Detachment

Although bone tired and filled with melancholy, with the wounded taken care of and the burial out of the way, our attention turned toward our ultimate task: to rebuild our ship in hell's wake and to sail her home, to Alexandria.

The ship was in terrible structural condition, but she was a "happy ship." We all looked with anticipation to the adventure that awaited us because we had full confidence in our captain's ability to get us home. However, the formalities of life on board were strictly followed. Guards were posted and orders were given and carried out. Very soon with the help of land cranes and other equipment under the general supervision of our superb First Engineer, Lt. Commader K. Arapis, the repair of the ship was progressing at a fast pace.

Late in the afternoon of the next day, we had an unexpected but very joyful surprise. A caique approached ADRIAS and Captain "D" and our sailor Savakis emerged from it. Both were missing and presumed dead. However, Savakis, who had been blown to the sea when ADRIAS hit the mine, had rescued captain "D" when he, in turn, had been blown to the sea when his ship, Hurworth, hit a mine and sunk within minutes.

We all dropped what we were doing and ran toward the ladder. We lined up for the official salute for our flotilla commander coming on board [4]. Savvakis was exhausted but in good shape. However, captain "D," Sir Royston Wright, was obviously suffering (with a broken back). Luckily there was a caique available and he was immediately transferred to Smyrna. In time he recovered and went on to become an Admiral and Second Sea Lord.

The ship was in terrible structural condition, but she was a "happy ship." We all looked with anticipation to the adventure that awaited us because we had full confidence in our captain's ability to get us home. However, the formalities of life on board were strictly followed. Guards were posted and orders were given and carried out. Very soon with the help of land cranes and other equipment under the general supervision of our superb First Engineer, Lt. Commader K. Arapis, the repair of the ship was progressing at a fast pace.

Late in the afternoon of the next day, we had an unexpected but very joyful surprise. A caique approached ADRIAS and Captain "D" and our sailor Savakis emerged from it. Both were missing and presumed dead. However, Savakis, who had been blown to the sea when ADRIAS hit the mine, had rescued captain "D" when he, in turn, had been blown to the sea when his ship, Hurworth, hit a mine and sunk within minutes.

We all dropped what we were doing and ran toward the ladder. We lined up for the official salute for our flotilla commander coming on board [4]. Savvakis was exhausted but in good shape. However, captain "D," Sir Royston Wright, was obviously suffering (with a broken back). Luckily there was a caique available and he was immediately transferred to Smyrna. In time he recovered and went on to become an Admiral and Second Sea Lord.

Gumusluk, R&R

Gumusluk, R&R

Of course there was time for R&R, but there was nothing to do more than visiting Ali's Café and sitting on the beach. Or climbing on the nearby hill to watch the explosions and the paratroopers Luftwaffe was dropping on Leros. As strange as this pastime may sound today, it was a diversion from the ship's every day monotony, and a grim reminder of the potential dangers lurking for us on our way to Alexandria--Luftwaffe had absolute dominance of the sky in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Although the repairs were on schedule, still we were living in cramped quarters on board Adrias. Also several of the ship's compartments could not be repaired. So, in anticipation of our departure, in early November, Toumbas decided to send away all those whose jobs were not absolutely necessary for the sailing of the ship.

Shock, alarm, and bewilderment hit Ali's Café and Adrias' decks when the order was announced. The first reaction of those ordered to leave was to protest, nobody wanted to leave. But Toumbas, although touched by their patriotism, sense of duty, and their desire to continue risking their lives to follow him, hardening his heart against the pleas, headed off the objections with aplomb and some blunt explanations that he did not let sentiment influence his selection; they reluctantly realized that Toumbas was right.

The group under Drakaris and Kouremenos sailed on two caiques to Kastelorizo, and from there were transported to Alexandria. Thus, Adrias was left with a skeleton crew of nine officers and forty-six petty officers and sailors plus the British (communications) Liaison Officer, Lt. Walkinsaw, and a couple of his men.

We were saddened to see our friends and comrades go, but the truth of the matter was that our on board living conditions improved dramatically—as we had more and better food in addition to less cramped living quarters.[7] However, as the caiques receded in the horizon, we came together, we vowed to double and triple our efforts. And defying every rule of self-preservation we forged a cohesive workforce for our ship's survival and her eventual legendary return to her base.

Although the repairs were on schedule, still we were living in cramped quarters on board Adrias. Also several of the ship's compartments could not be repaired. So, in anticipation of our departure, in early November, Toumbas decided to send away all those whose jobs were not absolutely necessary for the sailing of the ship.

Shock, alarm, and bewilderment hit Ali's Café and Adrias' decks when the order was announced. The first reaction of those ordered to leave was to protest, nobody wanted to leave. But Toumbas, although touched by their patriotism, sense of duty, and their desire to continue risking their lives to follow him, hardening his heart against the pleas, headed off the objections with aplomb and some blunt explanations that he did not let sentiment influence his selection; they reluctantly realized that Toumbas was right.

The group under Drakaris and Kouremenos sailed on two caiques to Kastelorizo, and from there were transported to Alexandria. Thus, Adrias was left with a skeleton crew of nine officers and forty-six petty officers and sailors plus the British (communications) Liaison Officer, Lt. Walkinsaw, and a couple of his men.

We were saddened to see our friends and comrades go, but the truth of the matter was that our on board living conditions improved dramatically—as we had more and better food in addition to less cramped living quarters.[7] However, as the caiques receded in the horizon, we came together, we vowed to double and triple our efforts. And defying every rule of self-preservation we forged a cohesive workforce for our ship's survival and her eventual legendary return to her base.

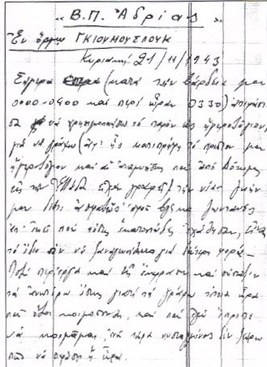

A page from Christos' log

A page from Christos' log

Soon after the groups' departure, I got the feeling I was witnessing some momentous events. I decided to keep a real log and not just notes here and there, as I had done up to then. So, one day while on watch duty at the stern, I found a booklet [5] whose title was "BOOK for the ACCOUNTING of EXCESS VICTUALS." In the first few pages there are still entries of the excess victuals. In the rest, I recorded what was happening from November 21, 1943 up to the middle of February 1945.

It's a treasured keepsake, tightly written with very small letters that I, too, have difficulty reading even with a magnifying glass! So, no wonder cousin George needed my brother Nikos to transcribe it for him.

It's a treasured keepsake, tightly written with very small letters that I, too, have difficulty reading even with a magnifying glass! So, no wonder cousin George needed my brother Nikos to transcribe it for him.

Caiques re-fueling Adrias

Caiques re-fueling Adrias

During our stay in Gumusluk we had become an object of curiosity, and a source of entertainment for the locals. Every day local residents, men and women, as well as, people from the surrounding villages, would come and sit on the beach, across from ADRIAS, for hours, watching us going about our business. Undoubtedly, among the lookyloos were spies reporting our progress.

In the afternoon of November 29, with all repairs done, Toumbas called a general meeting where he informed us about his plans without hiding or trivializing the dangers lurking in every mile on our way to Alexandria.

Besides his concern about the ship's seaworthiness for a 730 mile trip, he had an even bigger concern: Luftwaffe, the German air force, who had absolute control of the sky, even beyond the island of Rhodes.

Late that night a caique loaded with fuel in tin cans came to our starboard side to refuel us. We unloaded half of the cans the first night, each man carrying two 4-gallon petrol tins, pouring their contents into Adrias' fuel intake pipe. At dawn the caique shoved off and dropped anchor far away from us to avoid raising any suspicions about our impending departure. And the next night the process was repeated. In those two nights we replenish our tanks with approximately fifty tons of fuel. A very labor intensive job reminiscent of the coaling of Averof in India—but much cleaner than coaling, and, thankfully, without Adrias' "music detachment" playing music!

In the afternoon of November 29, with all repairs done, Toumbas called a general meeting where he informed us about his plans without hiding or trivializing the dangers lurking in every mile on our way to Alexandria.

Besides his concern about the ship's seaworthiness for a 730 mile trip, he had an even bigger concern: Luftwaffe, the German air force, who had absolute control of the sky, even beyond the island of Rhodes.

Late that night a caique loaded with fuel in tin cans came to our starboard side to refuel us. We unloaded half of the cans the first night, each man carrying two 4-gallon petrol tins, pouring their contents into Adrias' fuel intake pipe. At dawn the caique shoved off and dropped anchor far away from us to avoid raising any suspicions about our impending departure. And the next night the process was repeated. In those two nights we replenish our tanks with approximately fifty tons of fuel. A very labor intensive job reminiscent of the coaling of Averof in India—but much cleaner than coaling, and, thankfully, without Adrias' "music detachment" playing music!

Gumusluk, The Monument of Adrias' fallen.

Gumusluk, The Monument of Adrias' fallen.

The day and time of departure was set for December 1, 1943 at 8:30 pm, to give us as much of nighttime cover as possible. The overall plan was for three British MGBs (motor gunboats) to escort us to Kastellorizo for protection and for "pointing the way" because Adrias' compass and other navigation and detection systems were destroyed during the explosion.

Also, Captain Boutsaras, our Naval attaché in Smyrna, volunteered, above and beyond the call of duty, to act as our scout. He left Gumusluk a few hours ahead of us on a Turkish caique to warn us in case there were German ships awaiting for us.

On the day of our departure we installed on the grave the marble cross that had arrived from Smyrna, bearing the inscription "ΑΝΔΡΩΝ ΕΠΙΦΑΝΩΝ ΠΑΣΑ ΓΗ ΤΑΦΟΣ" (Andrōn epiphanōn pasa gē taphos) ,which roughly translates "For illustrious men their tomb could be at any land" —an excerpt from Pericles' funeral oration for the fallen after the first battles of the Peloponnesian War. ADRIAS' ship complement gathered around the monument and a priest who had come from Smyrna conducted a solemn memorial service. We bade an emotional "good by" to our fallen comrades and vowed to return some day [8] as victors to take them home.

After the service we returned to our "regular" routine to avoid arousing any suspicions about our impending departure.

I should mention here that after our departure rumors circulated that the Turks dug up our dead and gave their bones to the dogs. The story goes that the locals were expecting to loot ADRIAS if we were to abandon her. So, after our departure they turned their disappointment against our dead. These rumors were based on Peter Throckmorton's book The lost ships: An Adventure in Undersea Archeology (pp.133-134 and 258).

Years later, I had the opportunity to broach the subject with the then Admiral Toumbas. He categorically disagreed with Throckmorton because, after the war, he and Admiral Sotiriou were present during the ceremony of the remains being exhumed and transported to Greece. They did not observe any signs of desecration of the grave to substantiate such claims.

Moreover, Admiral Toumbas in his book (p. 594-596) has nothing but praise for the residents of Gumusluk and for the Turkish government regarding ADRIAS and her dead.

Also, Captain Boutsaras, our Naval attaché in Smyrna, volunteered, above and beyond the call of duty, to act as our scout. He left Gumusluk a few hours ahead of us on a Turkish caique to warn us in case there were German ships awaiting for us.

On the day of our departure we installed on the grave the marble cross that had arrived from Smyrna, bearing the inscription "ΑΝΔΡΩΝ ΕΠΙΦΑΝΩΝ ΠΑΣΑ ΓΗ ΤΑΦΟΣ" (Andrōn epiphanōn pasa gē taphos) ,which roughly translates "For illustrious men their tomb could be at any land" —an excerpt from Pericles' funeral oration for the fallen after the first battles of the Peloponnesian War. ADRIAS' ship complement gathered around the monument and a priest who had come from Smyrna conducted a solemn memorial service. We bade an emotional "good by" to our fallen comrades and vowed to return some day [8] as victors to take them home.

After the service we returned to our "regular" routine to avoid arousing any suspicions about our impending departure.

I should mention here that after our departure rumors circulated that the Turks dug up our dead and gave their bones to the dogs. The story goes that the locals were expecting to loot ADRIAS if we were to abandon her. So, after our departure they turned their disappointment against our dead. These rumors were based on Peter Throckmorton's book The lost ships: An Adventure in Undersea Archeology (pp.133-134 and 258).

Years later, I had the opportunity to broach the subject with the then Admiral Toumbas. He categorically disagreed with Throckmorton because, after the war, he and Admiral Sotiriou were present during the ceremony of the remains being exhumed and transported to Greece. They did not observe any signs of desecration of the grave to substantiate such claims.

Moreover, Admiral Toumbas in his book (p. 594-596) has nothing but praise for the residents of Gumusluk and for the Turkish government regarding ADRIAS and her dead.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

*From BOOK II of the Odyssey; Assembly of the people of Ithaca..

**In this context, the term "boys" is an egalitarian and endearing term rather than an insult to his men; equivalent to "Muchachos" is Spanish.

[1]"Enemy in Sight," Toumbas, , p.374

[2] Captain "D," Commander R. Wright, was blown to the sea and broke his back. He was rescued by Adrias' sailor A. Savvakis.

[3] "Enemy in Sight"

[4] Commander Right in his memoirs details his rescue by Savvakis. Also Toumbas has included Savvakis' story in his book "Enemy in Sight" p 389."Enemy in Sight"

[5] See picture in the "HOME" tab.

[6] On 10/23/1947

[7] Toumbas in his book, p. 399, mention this in more diplomatic terms : After the departure of the excess crew ... a special effort was made for the food and the health of the men.

[8] Four years later, on October 22, 1947, the remains were carried back to Greece and buried in the Naval Base of Skaramagas. See , "Enemy in Sight," Toumbas, p. 594-596.

[9] There were British personnel on board Adrias to ensure correct communications due to the language difference.