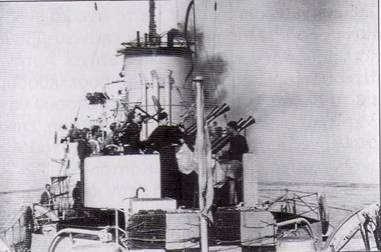

Christos, center, Adrias POM-POM in action

Christos, center, Adrias POM-POM in action

Operation Tableland:

It was December 1st, 1943. The eyes of the world were on "the ship that refused to die." The time had come for ADRIAS' epic journey to Alexandria, and into history.

ADRIAS' successful return to her home port of Alexandria was a matter of prestige for both the Germans and the Allies, albeit for different reasons. So much so, that the British had put in place a special operation code named: "Tableland." And, I suppose, the Germans had their own plans in place to see that we would not make it to Alexandria.

For sheer audacity, the Adrias epos is without parallel in naval warfare. Suffice it to say that when we made it Winston Churchill exuberantly announced our arrival in the British Parliament and the Commonwealth.

The overall plan was to sail only at night with the stern as a bow close to the Turkish coast escorted by three British MGBs the Admiralty had sent for navigation and protection because our navigation equipment was destroyed. The first stop would be at Loryma on the Turkish coast across from Rhodes. We would spend the daylight hours there and at night we would sail to Kastelorizo and Cypress. From there, being outside Luftwaffe's range, we would make a relatively safe dash to Alexandria.

All day we went about our business waiting until dark before starting the engines so that the smoke from the stack would not betray our impending departure. Some went for their usual coffee break at Ali's coffee shop, while others took a walk on the beach. Meanwhile late in the evening, others, including myself, performed several nefarious covert actions designed to temporally divert the villagers' attention rather than to cause irreparable or costly property damage. Three of us ventured outside the village to cut the telephone line, thus temporarily isolating the village from the outside world and to destroy evidence of the secret line we had with Myristis (or Hasan Bey, the Greek officer working for the British Intelligence). A team of two swimmers disconnected the water line to ADRIAS and threw off the two mooring steel cables. And for good measures, just before departure, a small demolition party short-circuited some power lines plunging the village into darkness, thus giving us the opportunity to slip out unnoticed in the ensuing chaos.

All in all, nothing serious that in the light of the next day could not be repaired within a few hours and minimal, if any, cost to the villagers—we had neatly coiled the telephone wire we had cut off and left it at the base of the telephone pole. We knew there were spies among the villagers reporting our progress, but the majority of the villagers had treated us with respect and genuine hospitality. Nevertheless, these diversionary acts were necessary for a precious, if not life-saving, head start for us.

Around 11:30 am, as planned, Captain Boutsaras left with a caique to act as a screen in case German ships were in the area. Right on time, at 12:00 noon, we had the regular visit from the German reconnaissance plane. Once the plane had disappeared in the clouds, a couple of sailors quickly painted the bulkhead of the cut-off bows with the regular warship's gray color because the asbestos that it was covered with, for disinfecting, would have been easily visible, especially at night.

By 5:00 pm, the marble cross that had arrived from Smyrna was installed on the grave of our dead shipmates and a brief memorial service was conducted.

It was December 1st, 1943. The eyes of the world were on "the ship that refused to die." The time had come for ADRIAS' epic journey to Alexandria, and into history.

ADRIAS' successful return to her home port of Alexandria was a matter of prestige for both the Germans and the Allies, albeit for different reasons. So much so, that the British had put in place a special operation code named: "Tableland." And, I suppose, the Germans had their own plans in place to see that we would not make it to Alexandria.

For sheer audacity, the Adrias epos is without parallel in naval warfare. Suffice it to say that when we made it Winston Churchill exuberantly announced our arrival in the British Parliament and the Commonwealth.

The overall plan was to sail only at night with the stern as a bow close to the Turkish coast escorted by three British MGBs the Admiralty had sent for navigation and protection because our navigation equipment was destroyed. The first stop would be at Loryma on the Turkish coast across from Rhodes. We would spend the daylight hours there and at night we would sail to Kastelorizo and Cypress. From there, being outside Luftwaffe's range, we would make a relatively safe dash to Alexandria.

All day we went about our business waiting until dark before starting the engines so that the smoke from the stack would not betray our impending departure. Some went for their usual coffee break at Ali's coffee shop, while others took a walk on the beach. Meanwhile late in the evening, others, including myself, performed several nefarious covert actions designed to temporally divert the villagers' attention rather than to cause irreparable or costly property damage. Three of us ventured outside the village to cut the telephone line, thus temporarily isolating the village from the outside world and to destroy evidence of the secret line we had with Myristis (or Hasan Bey, the Greek officer working for the British Intelligence). A team of two swimmers disconnected the water line to ADRIAS and threw off the two mooring steel cables. And for good measures, just before departure, a small demolition party short-circuited some power lines plunging the village into darkness, thus giving us the opportunity to slip out unnoticed in the ensuing chaos.

All in all, nothing serious that in the light of the next day could not be repaired within a few hours and minimal, if any, cost to the villagers—we had neatly coiled the telephone wire we had cut off and left it at the base of the telephone pole. We knew there were spies among the villagers reporting our progress, but the majority of the villagers had treated us with respect and genuine hospitality. Nevertheless, these diversionary acts were necessary for a precious, if not life-saving, head start for us.

Around 11:30 am, as planned, Captain Boutsaras left with a caique to act as a screen in case German ships were in the area. Right on time, at 12:00 noon, we had the regular visit from the German reconnaissance plane. Once the plane had disappeared in the clouds, a couple of sailors quickly painted the bulkhead of the cut-off bows with the regular warship's gray color because the asbestos that it was covered with, for disinfecting, would have been easily visible, especially at night.

By 5:00 pm, the marble cross that had arrived from Smyrna was installed on the grave of our dead shipmates and a brief memorial service was conducted.

First leg of the trip back to Alexandria

At 9:00 pm, under a starless and moonless sky, Toumbas gave the order. The gangway was hauled up, and the hawsers were loosened from the pilings. Slowly, ever so slowly, Adrias, barely seaworthy, freed herself from the sandy bottom of Gumusluk, on an even keel. She plunged in the waves with determination and pride and braved the Mediterranean with her blunt temporary "bow," flying her flag from her mast. From that moment on, unwittingly, we were making history. We were embarking on a daring mission into German controlled air and waters. An operation that could go down in the annals of naval history as either one of the most daring triumphs of all time or as one of the most brainless naval undertakings ever attempted.

The race was against daylight, not only to gain time until the local spies inform on us, but also to put miles between us and and the German air force. However, the moment we backed out of the bay, as we were watching the few lights of Gumusluk disappearing before our eyes, our enthusiasm soared. No one was thinking about the Luftwaffe or that we would be sailing through German-controlled waters. Or, worse yet, about the seaworthiness of our ship. Nothing could curb our enthusiasm. We were going home, to Alexandria! [1].

Meanwhile, a half hour earlier, the RAF had begun bombing the airport at Kos to divert the Germans' attention. Thus, operation "Tableland" had begun.

As planned, Toumbas tried to sail backward with the stern as a bow. Sailing this way had been discussed and had been deemed safer considering the enormous pressure the sea would exert on the temporary bulkhead covering the opening of our cut-off bows. However, sailing this way proved to be rather impossible. The ship was going in circles. Apparently, there were still several metal plates under the water line acting as rudder.

From the moment we pulled out of Gumusluk the ship's company was on "panfylaki," that is, 24-hour "General Quarters." As assistant gunnery officer, I readied the "Oerlikon" at the stern—our only means of defense because the fore turret was smashed and useless, precariously hanging on the top of the bridge, while the aft turret was unmanned.

I do not know why the aft turret was unmanned. Perhaps Toumbas thought that the ship, being in the condition that she was, could not defend herself against serious surface threats, but could manage lesser threats with the Oerilkon and the three British MGB escorts.

Since we were sailing with a substantially reduced ship's company, I was alone at the stern, manning the Oerlikon and piercing the darkness with my binoculars in search of sudden potential threats. I soon discovered what so many new Ensigns had learned before me that life is very different in the aft deck of a destroyer than in the crowded hallways of the Academy; I did not like the feeling of being alone without someone else to talk to. In reality, I was isolated from the rest of the ship except for having contact with the bridge via my telephone headset, and the periodic visit from the executive officer, Lt. Xaritopoulos, checking on me. Consequently, I did not have firsthand knowledge of the myriad of problems being discussed on the bridge or of the critical decisions made which Toumbas describes in detail in his book, "Enemy in Sight."

Adrias' engine had settled into what I would call under the circumstances "cruising" speed, and by the feel of the ship's motion, I knew that we were no longer in the gulf but had made it into the open sea. We were sailing in total darkness. Not even smoking was allowed. A blessing as far as I was concerned because I never indulged in that pastime. For safety, we followed a course as close to the Turkish coast as possible. The ship was riding low in the water with a considerable downward severe 15-degrees list to the port threatening to either sink or capsize us. The blades of the propeller were breaking the surface each time we rode the crest of a wave, followed by the terrifying slide down into the trough while being drenched by the spray of the cold sea breaking over the cut-off bows of the ship. And every time I was sure that we would continue our downward plunge into the abyss. But ADRIAS fought valiantly the sea, rising up again and again—while I was clinging tightly to the Oerlikon to avoid being swept overboard. Moreover, having no prow progress was intermittent, especially when the helmsman could not keep ADRIAS from being hit head-on. The ship would lunge forward, stop and shudder, and then slide backward as if she was a discarded wooden box pushed by the waves.

The sail protocol of our little convoy was a typical semi-star formation. In the front was one of the MGB’s guiding us since we had no compass and all our navigation instruments had been damaged by the explosion. And the other two were to the right, one a few yards ahead of us and the other a few yards behind.

We were about to enter the narrow passage between the island of Kos and the Turkish coast when a very strong searchlight suddenly came to life. Its beam started sweeping slowly toward us. My immediate thought was that we had been betrayed! I looked up into the sky, but nothing was heading our way at that moment. I anxiously waited for orders although I knew very well that the MGBs and my Oerlikon were no match for Stukas or the island’s fortified German gun batteries—at best, we could end up prisoners of war, I thought!

Luckily, seconds before the light beam reached us, a godsend rain squall drenched us to the bone and miraculously “put out” the searchlight. Darkness and that downpour saved us; undoubtedly, St. Nicholas, the patron saint of all mariners, was with us. But our feelings or relief did not last very long. A few minutes later, when the downpour stopped, to our horror, the searchlight came on again moving toward us with vengeance, faster than before. Terrified and in absolute silence all eyes on ADRIAS were riveted on the “deadly” light beam dancing on the surface of the sea racing toward us. Then suddenly rose toward the sky, passed over us, and continued going. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief—another miracle?

For sure, I was not the only one on board who said a silent prayer for that deliverance. However, the danger was not over. We knew the searchlight would sweep back. But before we had time to process that thought, an even greater threat appeared as though from nowhere: A huge German hospital ship bearing down on us with her lights blazing, the red cross on her side illuminated, and a huge red banner emblazoned with a jet black swastika on her mast fluttering in the wind. Even though my heart was pumping with adrenaline, I was momentarily transfixed by what I was seeing. Every apprehension I had had about the mission began asserting itself, and images of my parents and my brothers echoed in my head as that big red banner was getting bigger by the second threatening to envelop us. I was sure she would ram us, sailing without running lights and in absolute darkness. And considering the condition of our ship, it would not have taken but a slight bump and ADRIAS would have rolled over--we were doomed!

I instinctively grabbed the gun's handle as I swung around in the turret platform, as much as its small size allowed, and braced myself for the impact while waiting for orders to fire. That cleared my head and made the butterflies stop flapping in my stomach, and all the ominous thoughts dropped away. Then, seconds (?) before the impact, to my relief and disbelief, I saw the [hospital] ship's towering prow suddenly veer to a course parallel to ours, and the two ships peacefully passed in the night.

She passed slowly and silently very close to us, fifty yards(?), making ADRIAS look like a mere rowboat. She passed between us and the searchlight, thus rendering us invisible to the searchlight operator. No doubt “Lady Luck” was with us that night. And as I watched that hospital ship slowly and majestically receding in the darkness, I whispered in the wind "God be with you! " Perhaps Toumbas was right saying: “If God intended for ADRIAS to be sunk, He would have let her sink after the explosion.”

Whether it was Poseidon or St. Nicholas who sent that ship our way it is irrelevant. That hospital ship was our guardian angel in the most dangerous point during our journey. She passed so close to us that I can not imagine they did not see us, I could clearly see men walking on her deck. Ever since, I have been wondering why her captain did not betray us? Why did he intentionally sail parallel to us, thus concealing us from the shore gun-batteries? Was it his Teutonic warrior's chivalry for the wounded adversary, helping the unfortunate and unprotected? Or was it that his sense of duty was tempered by the suffering of those on his ship? Who knows! I hope, though, God rewarded him for his good deed with a long and happy life and that He shed His mercy on all those on board his ship.

[Author’s note: In 2015, watching the CBS “60 Minutes” about the WW II German Cemetery in Crete, I witnessed another manifestation of our common humanity similar to the chivalrous act of that German Captain. It was the poignant reply the caretaker of the cemetery, an old woman who undoubtedly had relatives killed during the Battle of Crete, gave to the "60-minutes" correspondent when he asked her: “Why are you taking care of them?” Her reply: “They too had a mother!" (Και αυτοι ειχαν μανα! ). Such a simple yet powerful statement that transcends ethnic lines, bellicosity, and the wounds of war.]

About 10:00 pm we went around cape Kefalouka, so close to it that you could almost reach out and touch it. That was too tempting for the Turkish shore patrol. They commenced firing at us but to avoid attracting unnecessary attention to ourselves we did not engage them. We could see the fire of the Turkish guns, which, with the exception of a few superficial bullet holes on our side neither Adrias nor the MGBs had any casualties.

As soon as we came out of the strait, we turned east to put as much distance between us and Kos as our fuel supply would allow, before turning south. Meanwhile, dark clouds were gathering, the wind was howling like a wolf pack on the prowl, and the weather was turning into a storm of unbelievable savagery, with waves towering as high as forty feet. It was obvious to all on board that the ship was “suffering.” We could hear a dirge the wind was blowing through the rigging while the throbbing pulsation of the pumps, working overtime trying to stave off the sea pouring in from sinking the ship, was a constant reminder of the great peril we were in. The ship, more than before, was moving like a “wooden box” tossed by the waves, in a cadence of “two steps forward and one step back”—every lurch of the ship threatening to snap the protective makeshift bow.

It was a harrowing pitch-black six-hour journey that cut through enemy controlled waters before we rounded cape Krios to head east toward the strait of Symi. The weather was getting worse. Rain had begun to fall, needle-sharp against the skin; a torrential downpour drenching all on deck. There was so much water coming down that I continuously had to turn upside down the telephone receiver to empty the water from the microphone. Nevertheless, the rain was a blessing. The foul-weather concealed us from being spotted or, worst yet, from being bombed by the German Air Force that still had absolute supremacy of the skies at that part of the world.

Just before dawn, rain abated followed by a cold gale, a blinked message from a ship’s screened light pierced the darkness. It was from the Gumhuriet, the Turkish caique on which Captain Boutsaras was on. Boutsaras had departed ahead of us from Gumusluk to act as a scout in case German ships were lurking. The weather was getting worse. As we rounded cape Aloupo the wind shifted direction kicking up a gale. Huge waves began pounding the sides of ADRIAS, tossing her here and there and drenching everything and everyone on deck with enormous amounts of water. It felt like being on an island in the midst of an earthquake and a tsunami. The danger of being swept into the sea was ever present. Below decks, pots, pans, clothes, wrenches, and furniture chased each other from side to side. The bulkhead creaked, while every lurch of the ship threatened to crash the temporary bows. Meanwhile, the drop in visibility to a few yards, due to heavy fog, was like a left-handed gift from God. On one hand, it minimized the risk of being detected by the nearby German garrison in Rhodes; on the other, it made it practically impossible to rescue someone if he was swept off the deck.

At 6:30 am, after nearly eighty-six miles, our small flotilla entered the small but physically well-protected cove of Loryma. ADRIAS having no bow could not drop anchor. Captain Toumbas had to beach her again on a sandy section of the beach.

Wet, exhausted, and running on adrenaline we were looking forward to relaxation before we were to begin the second leg of our trip at nightfall to Kastellorizo and Cypress. However, before we could relax we had to repair the damages from last night’s rough seas. First and foremost among them was the reinforcement of the temporary “bows.” And although we had not slept for over twenty hours, sleep was eluding us.

Much to our consternation, around noon, while the repair activities were taking place, we heard the buzz of a plane engine. I don’t think they spotted us, due to the cloudy weather, but it was a clear indication that Luftwaffe was still looking for us. That took care of the commonly held exuberant notion among officers and ratings that the most dangerous part of our trip was behind us.

At sunset, we sailed out of Loryma toward the strait of Rhodes. We veered to the left hugging the Turkish coast to avoid detection from the German radar in Rhodes. The weather was changing for the better. The night air was warm and humid, the sea calm and the sky clear. What little chop there was, ADRIA's cut-off bow effortlessly cut through it. The rest of the trip to Kastellorozo was rather uneventful.

As we were approaching Kastellorozo, looking out into the early morning hazy horizon off the missing bows of Adrias, I could see two destroyers waiting for us. There were the British fleet destroyers Jarvis and Penn. We continued sailing under their escort and around 9:00 am the flotilla entered the Turkish cove of Kakava where a powerful tug-boat, the Brigand, was waiting for us, complements of the Admiralty, to tow us the rest of the way.

We were visited by a low flying German reconnaissance plane around noon. Now there was no question whether they spotted us, the question was when they would attack!

The skippers’ consensus was that the Germans would not expect the heavily wounded ADRIAS to venture a daylight escape in the open sea and that they would be looking for us along the Turkish coastline. Therefore, the order was given for immediate departure with a southerly heading toward Cypress.

We left around 4:30 pm for Cypress with Brigand towing us by the stern, but the ship was difficult to control. Our progress, even under fair weather and clear skies, was very slow. Evidently, the wreckage under the water line not only slowed us down but it was acting as a rudder. We sailed that way all night. Early in the morning, Toumbas ordered to sail the “normal” way, that is, with our cut off front as the bow.

At around 8:00 pm, hundreds of flares illuminated the Turkish coast. The German Air Force was looking for us!. I am sure there was an Iron Cross of the highest order waiting for any German pilot who could do us in. The decision to brave the open sea during daylight saved us from being bombed and sunk. Unfortunately, Kastelorizo paid dearly for that decision. The Germans took out their frustration for not finding us somewhere along the Turkish coast on the small island. They bombed it for a long time with uncalled for ferocity.

But the Germans had planes up everywhere and by no means were like the Keystone Kpos that could not find their way ouside Berlin. They would soon realize their mistake! With dread, I was listening intently for the buzz of airplane engines, counting the minutes as ADRIAS twisting and bending was sliding over the waves, with every bolt and rivet creaking, trying to put miles between ourselves and Luftwaffe. Perhaps a rising mist which had turned the evening dark and cold made them to give up the chase.

The 2nd leg of the trip back to Alexandria

The 2nd leg of the trip back to Alexandria

On December 4 at 7:30 pm, we entered the harbor of Lemessos. Every man was exhausted, yet our spirits were high. With Alexandria beckoning, it seemed that we had discovered a new capacity in ourselves. We took fuel and stores and at daybreak of the next day departed for Alexandria escorted by Jarvis and Penn who later on were relieved by the destroyers Exmoor and Aldenham.

Under the escort of two destroyers and well outside Luftwaffe's reach, our spirits were high. Despite the exhaustion, a euphoria was growing with each passing mile. We could not wait to bring our ship back to her base.

Before noon on December 6, 1943, the feast day of St. Nicholas the patron saint of all mariners, the port of Alexandria came into view from a distance.

ADRIAS was limping along with a huge cavernous gap in the front instead of the bow of an aesthetically beautiful newly commissioned ship. She was looking more like an iron box loaded with guns than a warship. In the esprit de corps of the navy, warships under orders of “berthing” have to have “excellent” appearance. Thus, even under these conditions, no one was surprised when Toumbas gave the order to “prepare." The ship was cleaned, as much as possible under the circumstances, despite the fact that most of the pumps and the other cleaning machinery did not work, nor did we have the luxury of an unlimited fresh water supply.

In contrast with her external appearance, everything on the deck and on the crumpled bridge was neatly in place, even the brass fittings were polished! All crew, officers, petty officers, and sailors, were ordered at their stations for “all hands on deck for entering harbor.” We were clean, shaven, and wearing our uniforms as if nothing had happened the previous forty-five days of trials and tribulations.

Of course, a special effort had been made before arriving in Alexandria for our appearance because most of us, due to the explosion, had lost all or most of our possessions, including clothing. So, we had to borrow from each other. That is why in the picture (ADRIAS entering harbor, below) the men wear a variety of shoes.

A mile or so before entering the harbor the Greek minesweeper, Salamina, sped toward us. On her bridge were all the senior Navy commanders based in Alexandria and on her decks a huge number of fellow officers and crews.

As Salamina went by, they saluted us, according to the old Navy custom, with three thunderous cheers and with hats in hand raising them in unison high above their heads. Then, Salamina made a U-turn and followed us as honorary escort. And when she came alongside with ADRIAS's bridge, the dignitaries aboard her doffed their hat in reply to Toumbas' salute.

As we were approaching the harbor entrance, we could clearly see two motorboats speeding toward us. Once they got close they, too, made a U-turn and followed us, one on the right and the other on the left.

Under the escort of two destroyers and well outside Luftwaffe's reach, our spirits were high. Despite the exhaustion, a euphoria was growing with each passing mile. We could not wait to bring our ship back to her base.

Before noon on December 6, 1943, the feast day of St. Nicholas the patron saint of all mariners, the port of Alexandria came into view from a distance.

ADRIAS was limping along with a huge cavernous gap in the front instead of the bow of an aesthetically beautiful newly commissioned ship. She was looking more like an iron box loaded with guns than a warship. In the esprit de corps of the navy, warships under orders of “berthing” have to have “excellent” appearance. Thus, even under these conditions, no one was surprised when Toumbas gave the order to “prepare." The ship was cleaned, as much as possible under the circumstances, despite the fact that most of the pumps and the other cleaning machinery did not work, nor did we have the luxury of an unlimited fresh water supply.

In contrast with her external appearance, everything on the deck and on the crumpled bridge was neatly in place, even the brass fittings were polished! All crew, officers, petty officers, and sailors, were ordered at their stations for “all hands on deck for entering harbor.” We were clean, shaven, and wearing our uniforms as if nothing had happened the previous forty-five days of trials and tribulations.

Of course, a special effort had been made before arriving in Alexandria for our appearance because most of us, due to the explosion, had lost all or most of our possessions, including clothing. So, we had to borrow from each other. That is why in the picture (ADRIAS entering harbor, below) the men wear a variety of shoes.

A mile or so before entering the harbor the Greek minesweeper, Salamina, sped toward us. On her bridge were all the senior Navy commanders based in Alexandria and on her decks a huge number of fellow officers and crews.

As Salamina went by, they saluted us, according to the old Navy custom, with three thunderous cheers and with hats in hand raising them in unison high above their heads. Then, Salamina made a U-turn and followed us as honorary escort. And when she came alongside with ADRIAS's bridge, the dignitaries aboard her doffed their hat in reply to Toumbas' salute.

As we were approaching the harbor entrance, we could clearly see two motorboats speeding toward us. Once they got close they, too, made a U-turn and followed us, one on the right and the other on the left.

ADRIAS, Entering Harbor

ADRIAS, Entering Harbor

On board of the one on the right was our then Minister of the Navy, the late Sophocles Venizelos, with his staff. And on the other the British commander of Alexandria, Admiral Poland, with his staff. They enthusiastically saluted us. Meanwhile, five or six other more motorboats, from several Greek and allied warships, jam-packed with naval personnel, joined us as honorary escorts, while those on board were wholeheartedly cheering us.

As we were approaching a large British Battleship, we saw her crew lined up at the stern. We thought that they were undergoing an inspection. But when we came closer and before we stopped all engines to salute them, according to the naval custom, we heard an order coming from her loudspeaker and then a myriad of hats were lifted toward the sky and a thunderous “hip hip, HOORAY; hip hip, HOORAY; hip hip, HOORAY,” the traditional British victory cheer, resounded throughout the harbor.

The harbor was full of warships of all allied nations, British, French, Polish, Dutch, and Greek. From every ship we passed by they saluted us in the same manner, HOORAAAY! The minesweepers and the merchant ships whistled the letter “V,” standing for “VICTORY,” the common wartime salutation.

As we were approaching a large British Battleship, we saw her crew lined up at the stern. We thought that they were undergoing an inspection. But when we came closer and before we stopped all engines to salute them, according to the naval custom, we heard an order coming from her loudspeaker and then a myriad of hats were lifted toward the sky and a thunderous “hip hip, HOORAY; hip hip, HOORAY; hip hip, HOORAY,” the traditional British victory cheer, resounded throughout the harbor.

The harbor was full of warships of all allied nations, British, French, Polish, Dutch, and Greek. From every ship we passed by they saluted us in the same manner, HOORAAAY! The minesweepers and the merchant ships whistled the letter “V,” standing for “VICTORY,” the common wartime salutation.

THEY GOT HER HOME

THEY GOT HER HOME

Every ship in the harbor saluted us with whistle shrieks and dipping flags. Even the sailors from the disarmed Vichy Regime ships were saluting us as we were passing by.

Great rejoicings, without doubt, were made on our arrival. Only then did we realize the kind of reception the British had prepared for us and the great honor they bestowed upon us. Throughout the duration of the war in the Mediterranean, only in two other cases, a similar reception had taken place. The first time was when the British fleet, under Admiral Cunningham’s command, returned victorious from the battle of Matapas. And the second time when Admiral Baines’ fleet of cruisers returned triumphant from that famous convoy to Malta.

It’s worth mentioning, though, that in both of these cases the “salute” was given to the entire fleet and not to a single ship as it was done with ADRIAS.

All hands on ADRIAS, from the captain to the last sailor, were deeply touched. With tears in our eyes, nobody spoke. Nobody could speak. Emotions were high.

I believe that only an experienced sailor can fully appreciate the merits of this tremendous feat of seamanship, notwithstanding the war conditions. That is why the British, being world-renowned sailors, displayed such enthusiasm.

We received countless congratulatory signals from all authorities, such as the British Admiralty, the British Commander-in-Chief for the Mediterranean, Admiral Cunningham, and from many other Allied commanders. And next day's newspaper said it all in four words: "THEY GOT HER HOME."

As we were approaching our anchorage, next to a British warship, the ship was in the grip of jingoism. Our captain issued an "all hands muster" call on the quarterdeck after docking. We all stood at attention, with misty eyes, where our captain, very moved, saluted, congratulated, and thanked us all for our service and commitment to duty. And with a thunderous "Ζητω η Ελλας" (Long Live Greece) we broke ranks.

Great rejoicings, without doubt, were made on our arrival. Only then did we realize the kind of reception the British had prepared for us and the great honor they bestowed upon us. Throughout the duration of the war in the Mediterranean, only in two other cases, a similar reception had taken place. The first time was when the British fleet, under Admiral Cunningham’s command, returned victorious from the battle of Matapas. And the second time when Admiral Baines’ fleet of cruisers returned triumphant from that famous convoy to Malta.

It’s worth mentioning, though, that in both of these cases the “salute” was given to the entire fleet and not to a single ship as it was done with ADRIAS.

All hands on ADRIAS, from the captain to the last sailor, were deeply touched. With tears in our eyes, nobody spoke. Nobody could speak. Emotions were high.

I believe that only an experienced sailor can fully appreciate the merits of this tremendous feat of seamanship, notwithstanding the war conditions. That is why the British, being world-renowned sailors, displayed such enthusiasm.

We received countless congratulatory signals from all authorities, such as the British Admiralty, the British Commander-in-Chief for the Mediterranean, Admiral Cunningham, and from many other Allied commanders. And next day's newspaper said it all in four words: "THEY GOT HER HOME."

As we were approaching our anchorage, next to a British warship, the ship was in the grip of jingoism. Our captain issued an "all hands muster" call on the quarterdeck after docking. We all stood at attention, with misty eyes, where our captain, very moved, saluted, congratulated, and thanked us all for our service and commitment to duty. And with a thunderous "Ζητω η Ελλας" (Long Live Greece) we broke ranks.

"Oneiro demeno sto mouragio" (Elefsina, Greece) [1]

"Oneiro demeno sto mouragio" (Elefsina, Greece) [1]

So, this 730 miles marathon through enemy waters and with our ship nearly cut in half has ended! But the race toward total victory continued.

Leros was recaptured by the Germans, but the officers and men of Flotilla 22, under the command of Captain "D," made their mark in the annals of Allied seamanship.

And at the risk of sounding self-serving, I have known few instances where men, although our Navy is replete with glory and honor, were subjected to equal hardship as those on ADRIAS.

For the next fifteen days, we enjoyed a well-deserved shore-leave. Most of us were placed in hotels where others were taken in as house-guests by members of the Greek community in Alexandria. But regardless where we stayed, during those two weeks we were living in a dream. There was an atmosphere of fellowship, respect, and affection by our Greek and allied comrades.

Also, we had to have newly made uniforms because our old ones were either in shreds or had been lost during the explosion.

After our two-week shore leave, we departed for new ships and new adventures for the liberation of our country. I was sent to England as a crew member for the commissioning into the Greek Navy of a newly built destroyer, Aegeon, that the British were to give to the Greek Government. But fate intervened in the form of "The Incident at Chatham" that prevented that from happening, as we shall see next, in CHATHAM.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] "A dream tied up at the quay." A popular Greek song.

Leros was recaptured by the Germans, but the officers and men of Flotilla 22, under the command of Captain "D," made their mark in the annals of Allied seamanship.

And at the risk of sounding self-serving, I have known few instances where men, although our Navy is replete with glory and honor, were subjected to equal hardship as those on ADRIAS.

For the next fifteen days, we enjoyed a well-deserved shore-leave. Most of us were placed in hotels where others were taken in as house-guests by members of the Greek community in Alexandria. But regardless where we stayed, during those two weeks we were living in a dream. There was an atmosphere of fellowship, respect, and affection by our Greek and allied comrades.

Also, we had to have newly made uniforms because our old ones were either in shreds or had been lost during the explosion.

After our two-week shore leave, we departed for new ships and new adventures for the liberation of our country. I was sent to England as a crew member for the commissioning into the Greek Navy of a newly built destroyer, Aegeon, that the British were to give to the Greek Government. But fate intervened in the form of "The Incident at Chatham" that prevented that from happening, as we shall see next, in CHATHAM.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] "A dream tied up at the quay." A popular Greek song.