f

Christos, the future Commodore

In Memory of my cousins, Christos and Mimis

A first-hand account of the saga of “ADRIAS” through the eyes

of one of her young officers who actually was there, Christos E. Papasifakis.

Preface

In the Spring of 1941, my cousin, Commodore Christos E. Papasifakis, was a second-year cadet at the Hellenic Naval Academy (Σχολη Δοκιμων) when the front collapsed as a result of the onslaught of the German invading forces; forces technologically, tactically, and operationally much superior, if not light-years ahead of Greece's military in 1941.

With the “long night of barbarism descending on Greece,” [1] the King and the Government, as well as the fleet, fled to Crete and then to Alexandria, Egypt, to avoid capture by the Germans. Meanwhile, they issued an “indefinite leave of absence” to all cadets, officers and enlisted men. Thus Christos and other naval and army personnel were trapped in Greece, left to fend for themselves.

For Athens in 1941, unlike in "The Tale of Two Cities," it was only “the worst of times.” Besides a winter of unimaginable misery, shortly after the invasion a worthless armistice[2] was signed which resulted in a brutal German occupation with horrific consequences: Famine—which struck Athens particularly hard in 1941-1942 claiming 250,000 lives—imprisonments, mass executions, and deportations to German concentration camps.

Of course, the brunt of the deportations was born by the Jewish minorities in Athens and Thessaloniki, the main centers of Jewish life in Greece, and by the Jewish volunteers from Palestine who were part of the regiment that surrendered in Kalamata. And although I don't always agree with or admire the actions of the Hierarchy of my church, I am proud to mention that during that national tragedy the Greek Orthodox Church rose to the occasion and did everything possible to save our fellow Jewish citizens; issuing them fake baptismal certificates, cross necklaces, and hiding them with Christian families [10].

At times like these, young persons, and especially teenagers, cannot stay neutral. They either become collaborators, join the Resistance, or get out of the country. Christos and a couple of his fellow classmates could not see themselves idling under the German boot while their fleet had joined the Allied (British) Naval forces. They were eager to serve and be part of the war effort. So they immediately began planning their escape from Greece to join the fleet in Alexandria, Egypt.

A first-hand account of the saga of “ADRIAS” through the eyes

of one of her young officers who actually was there, Christos E. Papasifakis.

Preface

In the Spring of 1941, my cousin, Commodore Christos E. Papasifakis, was a second-year cadet at the Hellenic Naval Academy (Σχολη Δοκιμων) when the front collapsed as a result of the onslaught of the German invading forces; forces technologically, tactically, and operationally much superior, if not light-years ahead of Greece's military in 1941.

With the “long night of barbarism descending on Greece,” [1] the King and the Government, as well as the fleet, fled to Crete and then to Alexandria, Egypt, to avoid capture by the Germans. Meanwhile, they issued an “indefinite leave of absence” to all cadets, officers and enlisted men. Thus Christos and other naval and army personnel were trapped in Greece, left to fend for themselves.

For Athens in 1941, unlike in "The Tale of Two Cities," it was only “the worst of times.” Besides a winter of unimaginable misery, shortly after the invasion a worthless armistice[2] was signed which resulted in a brutal German occupation with horrific consequences: Famine—which struck Athens particularly hard in 1941-1942 claiming 250,000 lives—imprisonments, mass executions, and deportations to German concentration camps.

Of course, the brunt of the deportations was born by the Jewish minorities in Athens and Thessaloniki, the main centers of Jewish life in Greece, and by the Jewish volunteers from Palestine who were part of the regiment that surrendered in Kalamata. And although I don't always agree with or admire the actions of the Hierarchy of my church, I am proud to mention that during that national tragedy the Greek Orthodox Church rose to the occasion and did everything possible to save our fellow Jewish citizens; issuing them fake baptismal certificates, cross necklaces, and hiding them with Christian families [10].

At times like these, young persons, and especially teenagers, cannot stay neutral. They either become collaborators, join the Resistance, or get out of the country. Christos and a couple of his fellow classmates could not see themselves idling under the German boot while their fleet had joined the Allied (British) Naval forces. They were eager to serve and be part of the war effort. So they immediately began planning their escape from Greece to join the fleet in Alexandria, Egypt.

The future Rear Admiral

The future Rear Admiral

They planned and they conspired but their best-laid plans hit a snag: Mimis!

Mimis, as the family affectionately called him, was Christos’ sixteen-year-old brother, Demetris [3], the future Rear Admiral, who caught wind of Christos’ plans and with their parents’ blessings joined the group; leaving behind their thirteen-year-old brother, Nikos, to console their parents during their four-year absence, and later to become himself a young hero in the Resistance.[11]

Their escape plan was ambitious and daring, if not quixotic or insane. An adventure rising to the level of the Odyssey and the Argonaut expedition. The kind of voyage undertaken more by seasoned secret agents and well-trained commandos than by a group of inexperienced young men full of patriotic fervor and nothing more.

Miraculously, they made it to Alexandria. Christos completed his studies at the re-instituted Naval Academy aboard the cruiser “AVEROF" while pulling double duty as sailor and Academy student until his graduation. Mimis, although only sixteen, was allowed to take the entrance exam and successfully entered the Naval Academy’s-in-exile first freshman class in Alexandria while serving as a sailor until his graduation.

Both brothers participated in some of the most dangerous missions; battling U-boats in rough seas, dodging stuka[4] bombs, and sailing through blizzards and gale-force winds from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. With God’s grace both returned unharmed after the Liberation, eventually to become Flag Officers and a source of pride and inspiration for their younger brother and their five cousins [5].

In retrospect, it is amazing how normal they returned to us after what they saw, did, and suffered. And so humble about their stature as ones of the war's active participants.

Their younger brother, Nikos, remembers that for a long time after 1941 the family had no idea of his brothers' whereabouts. At one point, his father was told that his sons had been spotted in the Agora (marketplace) in Crete just before the German invasion of the island. However, with the huge number of casualties during the Battle of Crete, they feared the worst.

Nikos will never forget that day in December, 1942, when hanging out with friends, another friend ran up to him and said “Hurry, hurry, something has happened to your father!” He immediately ran toward his father’s office, only to see him running in his direction holding a piece of paper in his hand. It was a telegram from the Red Cross, which had been mailed from Alexandria in the summer (about six months ago). It read in French[6]: “Mimis and I are safe. Christos.”

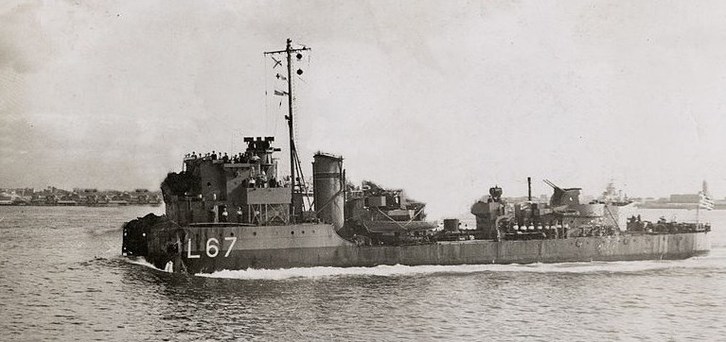

Sadly, Mimis passed away on January 1, 2001. But Christos, being one of the few surviving naval officers of the WW II era, has since become a sought-after speaker about WWII, and in particular about the story of the legendary destroyer ADRIAS.

Amendment: I was saddened to learn of Christos' passing on July 24, 2014, a year after visiting him in Greece. A thankful nation appreciative of our beloved cousin's service in war and peace had military honors rendered at his funeral (see newspaper photos: http://www.aparaskevi-images.gr/?p=47492

The Municipality of Ag. Paraskevi honoring Christos: http://www.aparaskevi-images.gr/?p=13292

Mimis, as the family affectionately called him, was Christos’ sixteen-year-old brother, Demetris [3], the future Rear Admiral, who caught wind of Christos’ plans and with their parents’ blessings joined the group; leaving behind their thirteen-year-old brother, Nikos, to console their parents during their four-year absence, and later to become himself a young hero in the Resistance.[11]

Their escape plan was ambitious and daring, if not quixotic or insane. An adventure rising to the level of the Odyssey and the Argonaut expedition. The kind of voyage undertaken more by seasoned secret agents and well-trained commandos than by a group of inexperienced young men full of patriotic fervor and nothing more.

Miraculously, they made it to Alexandria. Christos completed his studies at the re-instituted Naval Academy aboard the cruiser “AVEROF" while pulling double duty as sailor and Academy student until his graduation. Mimis, although only sixteen, was allowed to take the entrance exam and successfully entered the Naval Academy’s-in-exile first freshman class in Alexandria while serving as a sailor until his graduation.

Both brothers participated in some of the most dangerous missions; battling U-boats in rough seas, dodging stuka[4] bombs, and sailing through blizzards and gale-force winds from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. With God’s grace both returned unharmed after the Liberation, eventually to become Flag Officers and a source of pride and inspiration for their younger brother and their five cousins [5].

In retrospect, it is amazing how normal they returned to us after what they saw, did, and suffered. And so humble about their stature as ones of the war's active participants.

Their younger brother, Nikos, remembers that for a long time after 1941 the family had no idea of his brothers' whereabouts. At one point, his father was told that his sons had been spotted in the Agora (marketplace) in Crete just before the German invasion of the island. However, with the huge number of casualties during the Battle of Crete, they feared the worst.

Nikos will never forget that day in December, 1942, when hanging out with friends, another friend ran up to him and said “Hurry, hurry, something has happened to your father!” He immediately ran toward his father’s office, only to see him running in his direction holding a piece of paper in his hand. It was a telegram from the Red Cross, which had been mailed from Alexandria in the summer (about six months ago). It read in French[6]: “Mimis and I are safe. Christos.”

Sadly, Mimis passed away on January 1, 2001. But Christos, being one of the few surviving naval officers of the WW II era, has since become a sought-after speaker about WWII, and in particular about the story of the legendary destroyer ADRIAS.

Amendment: I was saddened to learn of Christos' passing on July 24, 2014, a year after visiting him in Greece. A thankful nation appreciative of our beloved cousin's service in war and peace had military honors rendered at his funeral (see newspaper photos: http://www.aparaskevi-images.gr/?p=47492

The Municipality of Ag. Paraskevi honoring Christos: http://www.aparaskevi-images.gr/?p=13292

Christos' Journal

Christos' Journal

As a youngster, I could not understand the importance or the beauty of that huge framed picture of a shipwreck [Adrias] hanging in my aunt Katina’s, Christos' mother’s, living room. Little did I know then that one of those whitecaps on it was our dear cousin Christos. And although later on, as I was growing up, I had heard with fascination bits and pieces of my cousins’ wartime exploits in faraway places with mysterious, if not magical, names like Gibraltar, Valletta, Alexandria, Khartoum, Bombay, Ceylon and about Stukas, torpedoes, elephants, tigers, and levitating fakirs; I did not have their whole amazing story of hardship and heroism on the high seas. Nor did I know about the Greek merchant marine's contributions which were of special and significant importance to the Allied cause.

In the summer of 2013, I visited Greece and spent some wonderful days with cousin Christos talking about those war stories of his, he was quite the raconteur. I was intrigued by what I heard. So, upon my return I decided, with his consent, to publish his stories; my first foray into non-technical writing [7]. Moreover, I believe Christos wanted me, out of all the cousins, to memorialize his stories because as the youngest cousin, having no personal experience of the WW II war years, I had no personal baggage to bring to the stories. Therefore, what follows is far from being a sanitized version of the stories. It is a (last?) survivor's story reminiscing about harrowing memories, deprivation, humor, and bold and courageous tales of bravery and sacrifice.

I have also included translations of excerpts from Christos' and Mimis' journals which Nikos, their brother, transcribed or read to me over the phone because time and the war conditions under which they were written had rendered them rather unreadable[8], at least to me.

In addition, I have included footnotes in order to give the reader (and myself) a sense of the times during which the events I described took place. Moreover, since I did not have the luxury of an editor, I apologize for any spelling, typographical, or syntactical errors and for any errors of omission or for minor factual mistakes.

Acknowledgements

Doing this project, I learned that translating narrations, journals, and records, especially on a topic outside one's expertise is not an easy task. Nevertheless, I did it as a labor of love and a debt of honor, as an elegy and a tribute to all those brave men on ADRIAS and by extension to all the brave Greek mariners whose valor and contributions toward the defeat of the enemy was of special importance to the Allied cause, but has seldom been acknowledged. Unsung heroes like Captain Vasilis, my father[12], who in defiance of the German authorities and at the risk of his life chose to abandon his requisitioned ship and swim fifty yards, under cover of night, to a remote beach in Kythira and freedom than delivering provisions and ammunition to the enemy in Crete. It took him three months of hiding and evading informants and Gestapo checkpoints to make it back home to Athens.

But I would be remiss if I did not say that I had to rely on many people for their knowledge and expertise. And to thank everyone in the manner properly deserved would require at least ... an additional website! And while I am taking full responsibility for errors of fact and interpretation, I do want to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to all who have helped me to complete this work. Prominent among them are:

* First and foremost, my two cousins: Christos and Nikos without whom this website would never have existed. Christos for opening his files to me and spending many pleasant hours regaling me with many war and ADRIAS stories during my 2013 visits to Greece. And Nikos, for his many hours on the phone from Bloomfield Hills, Michigan giving me a perspective on the events I was to write about. [9].

* My brother Kyriakos V. Krestas, a retired IBM engineer, for his objective and unfailingly honest criticism of the original manuscript and for providing me with detailed comments and marginal notes—a history buff and literary critic extraordinaire, and a dear brother indeed.

* My brother Demetrios V. Krestas, retired engineer, founder and CEO, MONOTHERM Inc., for sparing no effort or treasure to "educate" me about WW II with books and visits to Museums and historical sites—a dear brother and a remarkable businessman.

* My dear cousin Eleni Papasifakis, Mimis' widow, for sharing with me Mimis' war diaries.

* My dear niece Harriet K. McGraw, DDS, for researching her uncles', Christos' and Mimis', military bios.

* Dr. Nicholas Itsines, Director of the Greek Department, Defense Language Institute, DLI, in Monterey, CA., for his much-needed comments on the structure of the original manuscript.

* Prof. Spiros J. Politis, my former college roommate, an esteemed colleague, DLI instructor, and dear friend, for giving me a perspective on the Civil War from someone who lived outside the relative tranquility of Athens during those dark days of strife.

* CPT Tom MacRae, USN, Dean of Students, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA., and those under his command, LCDR Konstantinos Eletheriou and LTJG Ioannis Milonas for their kind and prompt assistance in translating for me nautical terms, from Greek to English;

* VADM Paloubis, Hellenic Navy (Ret.), and his esteemed wife Mrs. Anastasia Anagnostopoulou-Paloubis, President of the HELLENIC MARITIME MUSEUM, for providing me with books and valuable historical insights.

* CDR Kenn Christie, San Jose Police Department (Ret.), student of Greek history, patron of the Nemean Olympics, dear friend, and farmer par excellence for giving me the benefit of his careful review and his general comments derived from his experience as a decorated Vietnam war US Marine veteran.

* Weebly.com for graciously hosting the "adriaslegend" website.

* The following websites for allowing me to use some of their pictures:

* Ships Nostalgia: ( http://www.shipsnostalgia.com)

* Naval history net: ( http://www.naval-history.net)

* Hellenic Maritime Museum: (http://www.hmmuseum.gr )

* IMAGES, AG. PARASKEVI: (http://www.aparaskevi-images.gr/?p=48040)

George V. Krestas,

November 2013

San Jose, CA

[email protected]

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Winston Churchill’s description of the period: 1941-1944.

[2] General Tsolakoglou signed the armistice and was installed as Prime Minister of a Vichy-like government.

[3] The late Rear Admiral Demetris E. Papasifakis.

[4] The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from Sturzkampfflugzeug) dive bombers.

[5] The cousins: Christos, Mimis, and Nikos Papasifakis; Soulis, and Mimis Mourdjinis; Kyriakos, Takis, and

George Krestas.

Note: Mimis and Takis are nicknames for Demetris. We are the sons of the three sisters: Katina, Marika,

and Myrsini. According to the Greek tradition of the day, the first child in a family was named after the paternal grandfparent and the second after the maternal grandparent—our

maternal grandfather's name was Demetris, thus the second son in each family was

named Demetris.

[6] Red Cross messages were written in French, the “International” language of the time, to expedite

censorship.

[7] Engineering Professor, De Anza College, Cupertino, CA (profgvk.weebly.com)

[8] All pictures are from Commodore C. E. Papasifakis' file, except if otherwise noted.

[9] Footnotes are mine (George V. Krestas).

[10] A list of the Righteous of the World:

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/greekbishop.html

[11] Nikos joined the right-wing "X" resistance organization.

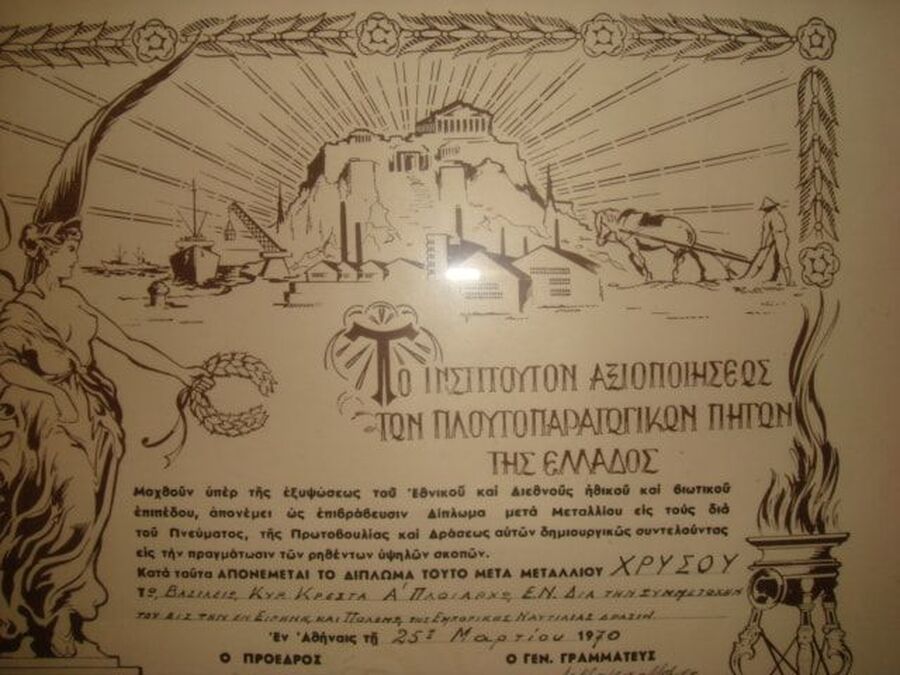

[12] During my 1980 visit to Greece, scavenging through the drawers in my parent’s home (my father passed away in 1973), I came across a "certificate of recognition" and its accompanying "gold" medal given to my father on March 25, 1970 from a "National Institute" for his “Contributions during War and Peace for the betterment of the Nation …etc., etc.” (see below).

I was surprised because I had never heard about it before nor did I ever remember my father portraying himself as a WW II war hero. So, with medal and certificate in my hands I ran to my mother in the living room for an explanation. My mother, with an impish look about her, smiled and said "oh, you found it!" Sit down, I'll tell you the story behind it.

Apparently, in 1970, during a patriotic paroxysm of the (1967-1974) “Colonels’ Junta,” the authorities looked for “War Heroes” everywhere they could find them to add more “glory” to their pompous celebrations (March 25th is a National holiday equivalent to the 4th of July in the USA).

For my father, being a lifelong royalist, accepting this honor from the “junta,” that, among the other bad things they had done, they had also deposed the King, was a double embarrassment. He did not want it! But thankfully--you don't say "NO" to Dictators--prudence prevailed and “graciously” accepted it! And as soon as he returned home, he buried it at the bottom of his dresser's drawer with strict orders to my mother never to talk about it. And that is why I had never heard about it.

Nevertheless, my mother allowed me to take it. I framed it and now hangs in my office making a conversation piece for the Junta's absurdity, and my father's mettle.